Ramón Pignatelli

The common good as a life goal

Saragossa, 1734-1793

Ramón Pignatelli was born in Saragossa into a family of the highest nobility. His father, of Neapolitan origin, was a prince of the Holy Roman Empire, and his mother, the heiress to numerous aristocratic titles, including the county of Fuentes. He had numerous brothers, some of whom excelled in politics, arts and letters. One of them, the Jesuit José Pignatelli, was elevated to the altars as a saint.

Ramón spent his early childhood in Saragossa, but in 1740 the family moved to Naples, where he lived until he was twelve years old, when he was sent to Rome under the protection of a cardinal uncle. There he began his ecclesiastical training and, at the same time, continued his studies, both in the humanities and in scientific subjects. He did so brilliantly that Pope Benedict XIV rewarded him by naming him a canon of the cathedral of Saragossa. He then returned to the Aragonese capital, where he took up his post in 1753. He did not, however, give up his training, and at university he graduated in Law, Canons and Philosophy and Letters, as well as taking courses in Natural Sciences, Physics and Mathematics.

The palace of the Condes de Fuentes, his family home, was the main art school in the city and was also the venue for a gathering attended by a group of enlightened men, including Ramón and his brother Vicente, who discussed economics, science and literature according to principles that were very advanced for the time. In fact, the University of Salamanca refused to authorise them to become the Academia del Buen Gusto (Academy of Good Taste), branding those who met there as “encyclopaedists”.

These enlightened ideas, which sought the modernisation of the country and the public utility of projects and investments, were put into practice by Ramón Pignatelli when he was appointed director of the Royal House of Mercy in Saragossa, which took in orphans and beggars. He improved its management so that it would generate income and would not depend on alms. He ordered the building of workshops and other facilities, with plans designed by himself, in which both boys and girls learned a trade and whose production was sold. The most important of these were for weaving, but there were also embroidery, tailoring, shoemaking, masonry, carpentry, baking, cooking and nursing. Another profitable source of income was the bullring he ordered to be built. The profits from the bullfights went entirely to the centre. The first bullfight took place in September 1764.

A year earlier, in 1763, he held the post of rector of the University of Saragossa for the first time, a circumstance that was repeated on another four occasions, the last in 1792. During his rectorship, the statutes of the institution were reformed and valuable improvements in teaching were implemented.

His interest in artistic subjects led him to chair the preparatory board in 1771, which was charged with organising the creation of an academy of fine arts that would move away from the customs and practices of the guilds, of medieval origin and still in force, in all matters relating to artistic teaching and the execution of works. But his efforts would not bear fruit until twenty years later, when Carlos IV, in 1792, gave his approval for the establishment of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Luis. Its birth was promoted by the Real Sociedad Económica Aragonesa de Amigos del País, created in 1776 to disseminate the ideas of the Enlightenment in Aragon as well as technical and scientific knowledge. Ramón Pignatelli was one of its main promoters and gave its inaugural speech.

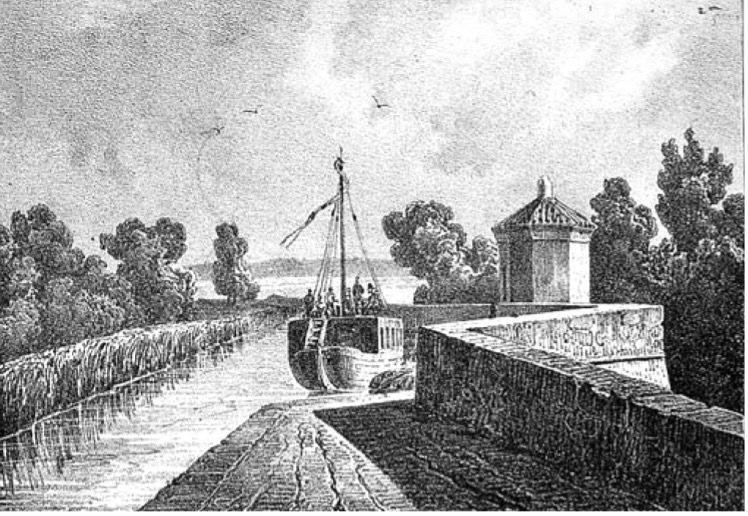

Not satisfied with all this incessant activity, Pignatelli also headed, from 1772, the enterprise for which he is most remembered today, the construction of the Imperial Canal of Aragon. The work had begun in the 16th century, in the time of Emperor Carlos V, hence its name. However, it had been abandoned after encountering serious technical problems. The main one was the need for its waters to cross the course of the river Jalón.

In accordance with the Enlightenment ideology of benefiting progress, the project had been taken up again a few years earlier and placed in the hands of a Dutch company. But the technical and, above all, financial problems did not disappear. It was then that the Conde de Aranda, president of the Council of Castile, appointed Pignatelli as protector of the Canal and granted him broad powers. With Pignatelli at the helm, the main objective of the actions was to provide irrigation water from the Ebro at a low price to a fertile but dry agricultural area. And, in addition, to establish a river navigation service that would allow the transport of goods and passengers.

Few believed that such ambitious plans could come to fruition. But Pignatelli did not shy away from the difficulties and set about overcoming all obstacles. With state funding and the help of several regiments of soldiers as manpower, a dam was built near Tudela, at the beginning of the Canal. Over the years, locks, bridges, mills and small ports were built, as well as the Tauste Canal, complementary to the main canal. In 1782 a large aqueduct over the Jalón was ready and two years later another wooden one over the Huerva. The water reached Saragossa in October 1784 and Pignatelli was received as a hero. The works were not completed until six years later, but before that Pignatelli had a fountain installed to celebrate the success of the mission and on which one can read: “For the conviction of unbelievers and the rest of travellers”.

At the time of Pignatelli’s death, the Canal extended a few kilometres downstream from the Aragonese capital. It was intended to reach as far as the Mediterranean, but the poor quality of the land prevented it from doing so. His titanic work, which had caused great opposition from some nobles and the Church, who lost land and tithes, benefited the working classes, especially the modest peasants and day labourers of Saragossa. As a token of admiration, the city decided to erect a public monument in his memory, a large bronze sculpture, the first in Saragossa since Roman times, the inauguration of which was delayed, however, until 1858.

References

- Antonio de las Casas y Ana Vázquez (2000): El Canal Imperial de Aragón. Zaragoza: CAI.

- Antón Castro (1993): “La sagrada autoridad de Ramón Pignatelli”, en Antón Castro y José Luis Cano, Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (pp. 120-125). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- León González Rodrigo (1984): Historia del Canal Imperial de Aragón.

- Guillermo Pérez Sarrión (1984): Agua, agricultura y sociedad en el siglo XVIII. El Canal Imperial de Aragón, 1766-1808, Zaragoza, IFC, 1984.

- Guillermo Pérez Sarrión, Guillermo Redondo Veintemillas y Fernando Baras Escolá (1997): Los tiempos dorados: estudios sobre Ramón Pignatelli y la Ilustración. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram%C3%B3n_Pignatelli

Teaching activities

The Enlightenment

The following video discusses the Enlightenment.

After watching it, indicate the ideas on which the Enlightenment was based and answer this short questionnaire. Note that although it was a movement more than two hundred years ago, it laid the foundations for today’s thinking.

What is the separation of powers?

Why is education so important to the Enlightenment?

Which French philosophers are central to the formation of Enlightenment thought?

What is the Encyclopédie and why did it have such an impact?

What fact favoured the development of the Enlightenment in Spain? Name some of its representatives.

The Enlightenment movement in Aragon

The Aragonese Enlightenment began to manifest itself from the mid-18th century onwards, expanding its influence in the last two decades of the century. Three different groups of protagonists took part in it:

-

- Nobles

- Members of the middle class, more open to the reforms proposed by the court.

- Aragonese personalities based in Madrid, where they held prominent positions in the political and cultural spheres.

Identify an enlightened Aragonese figure belonging to each of these groups.

Mention any specific initiative that was carried out in Aragon during the 18th century that had to do with the objectives set out below:

Like other Enlightenment groups, the Aragonese set themselves a series of objectives, among which the following stand out:

-

- Educational reform at the basic levels.

- Creation of study centres outside the University, to complete training in the scientific, humanistic and legal fields.

- Attention to public health (fight against epidemics, analysis of drinking water, vaccination campaigns, etc.).

- Adoption of measures to improve the situation of the begging population.

- Promotion of artistic education in accordance with the budgets of the time.

- Modernisation of agricultural machinery aimed at optimising resources.

- Creation of Economic Societies to promote legislative changes in economic matters.

Source: https://goya.unizar.es/InfoGoya/Aragon/IlustrAragon.html

Enlightened friends and the “Aragonese Party”

There had been an active Enlightenment movement in Aragon since the mid-18th century.

The Aragonese Enlightenment was characterised, on the one hand, by its concern for reform, as it sought to revitalise the regional economy in the face of the centralist tendency of Enlightenment despotism; and, on the other, by its notable participation in the leading ranks of the court. Two of its most representative men were the Conde de Aranda, in Madrid, as president of the Council of Castile and head of what some historians call the “Aragonese Party”, and Ramón Pignatelli, in Saragossa. With their intelligence and tenacity, they played an important role in bringing the long-desired project of the Imperial Canal to a successful conclusion. The moment and the circumstances favoured this great enterprise.

Look up some of the Aragonese personalities of the time who formed part of the so-called “Aragonese Party” (The Conde de Aranda, the Duke of Villahermosa, José Nicolás de Azara, Manuel Roda y Arrieta…) and point out which friends supported Pignatelli in his initiatives.

Do you know what the Real Sociedad Económica Aragonesa de Amigos del País is? When did it come into being? Was it the first in Spain? Did Ramón Pignatelli take part in it? What were its main activities? Search the internet for information about it.

Pignatelli initiatives

We have read in Ramón Pignatelli’s biography some of the initiatives that he carried out moved by the ideas of the Enlightenment and the desire for progress for Aragon. Describe those listed below, comment on what you think they were advanced for their time and whether they are still in operation today.

-

- Hogar de Misericordia (Mercy Home)

- Plaza de toros (Bullring)

- San Luis Academy

Imperial Canal of Aragon

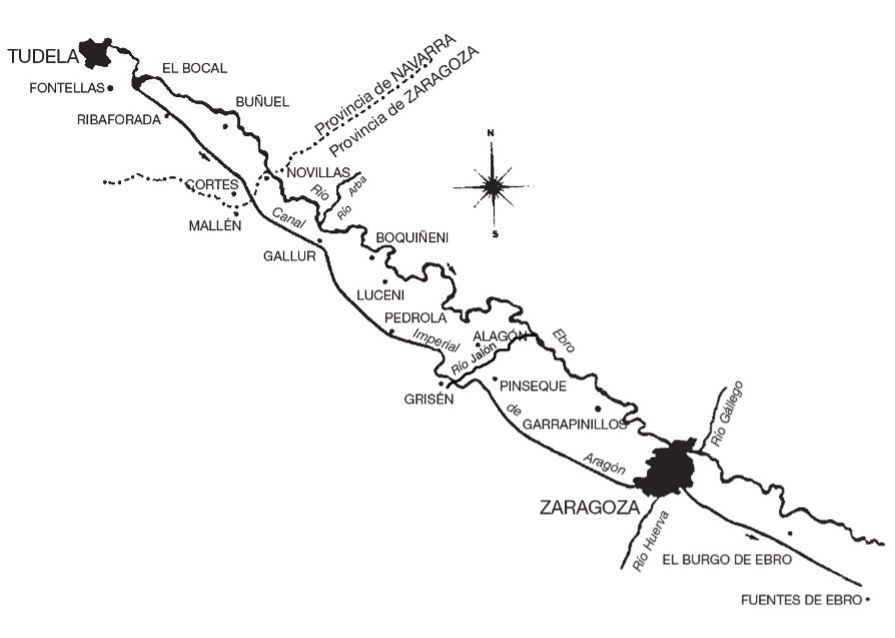

Ramón Pignatelli’s main work was the continuation of the Imperial Canal of Aragon, begun in the time of Carlos V, hence its name.

Look for information on its construction and on other similar works carried out in different European countries, so you can see the importance that this type of work had in 18th century Europe. You are sure to find related information on Wikipedia.

There are numerous illustrated canal projects, started in France in the 17th century, and continued in other countries such as Spain in the 18th century, for navigation as the main function, and irrigation as a secondary function. The canals of Braire, Languedoc or Midi, Burgogne or Loire in France, linking the headwaters of rivers with the sea, had their response in Spain from the mid-18th century with the Canal de Castilla project for which the Marquis of Ensenada brought Carlos Lemaur from France with the aim of providing an outlet for Castilian products through the Cantabrian Sea, 207 km of which were opened, and the Imperial Canal of Aragon, to connect the Cantabrian Sea with the Mediterranean, 101 km of which were opened, from the Bocal (downstream from Tudela) to past Saragossa, as artificial waterways to compensate for the lack of navigability of the natural rivers.

Other places where similar engineering works were carried out were France, Scotland and Russia, some with more success than others.

Look at the route of the Canal Imperial de Aragón. What difficulties do you see in its construction? Do you know how many kilometres were finally built? Was it navigable? What is it still used for today?

Pignatelli’s legacy

Where are traces of Pignatelli preserved today? Statues, streets, public works, institutions promoted by him… There are numerous traces left by this Aragonese figure in his passage through our history.

Find examples and explain some of their characteristics. Illustrate them with a current photograph.

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: