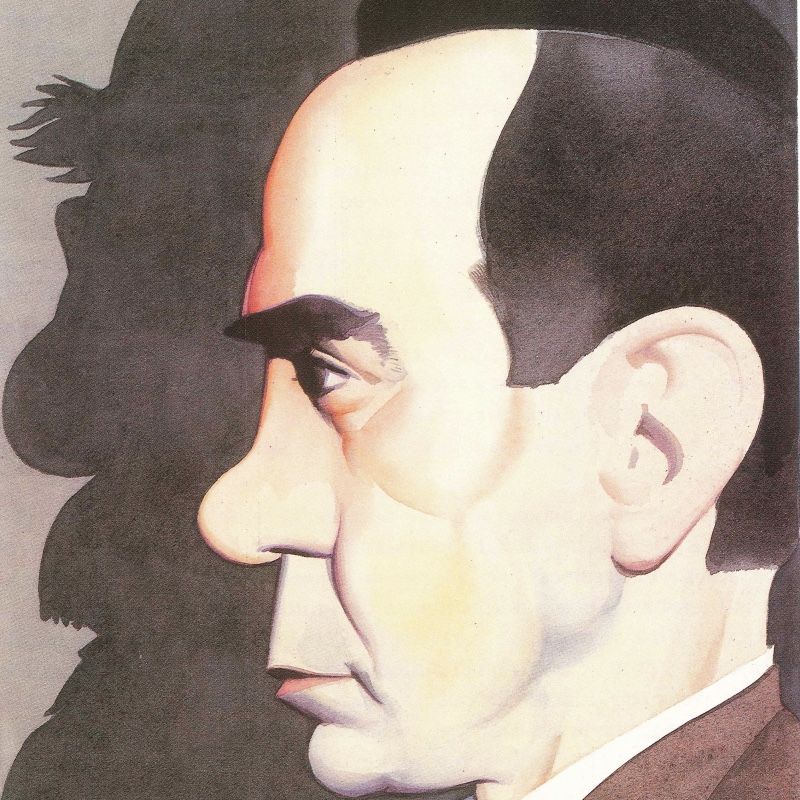

Ramón J. Sender

The writer’s identity in its eternal quest

Chalamera, 1901 – San Diego, 1982

The best Aragonese novelist of the 20th century lived his early years on the banks of the Cinca, in Chalamera and Alcolea (his parents, the teacher Andrea Garcés and José Sender, secretary of the town council, were from the latter village). His father’s professional destinies determined the family’s itinerancy. When, in an act of defiance of his father’s authority, the seventeen-year-old Ramón went to Madrid to discover the bohemian life, he had already lived in Tauste (where he found his first, innocent love in Valentina, daughter of the notary), Reus (a boarder at a school for friars), Saragossa and Alcañiz (where he finished high school after having been expelled from the secondary school in Saragossa, and worked as a grocer in an apothecary’s shop).

Life

He was living in Madrid, living from hand to mouth, enrolled in Philosophy and Letters, writing texts for the capital’s press (as a teenager he had already published stories in the Saragossan newspaper La Crónica de Aragón), beginning to sympathise with anarchist ideas… when his father legally forced him to return (he was still a minor) and, using his influence, put him in charge of the Huesca newspaper La Tierra, the tribune of the farmers and stockbreeders of Huesca. At the age of twenty-one he was called up and spent three years in Morocco, from where he would return to work on the editorial staff of the Madrid daily El Sol and undertake other journalistic collaborations, with the workers’ struggle and the opposition to Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship occupying an important place.

The experiences of the African War would mark him so much that he transferred them to his first novel, Imán (1930). During the Republic, while moving from anarchism to communism, he gradually made a name for himself in the literary and journalistic scene, with an extensive production that included Orden Público, Siete domingos rojos (which he rewrote in 1974 as Las tres sorores), Viaje a la aldea del crimen (about the events of Casas Viejas) and Mister Witt en el cantón, for which he won the National Literature Prize in 1936.

Work

The Civil War was a family tragedy for Sender. In the area dominated by the insurgents, his brother Manuel (who had been mayor of Huesca) was killed and his wife, Amparo Barayón, was killed in Zamora. He fought in the war, had serious differences (real hostility) with the Soviet communism represented by Enrique Líster, married the young Basque Elisabeth de Altube, with whom he had a son, Manuel… After recovering Ramón and Andrea (the two children he had had with Amparo) through the Red Cross, he left with them for America: he entrusted the care of his children to a New York couple and settled in Mexico, where he founded the publishing house Quetzal. In these early years of exile, he published novels as significant as El lugar de un hombre and Epitalamio del prieto Trinidad.

Crónica del Alba

In 1942 he began to give vent to his childhood and youthful memories and daydreams in Crónica del Alba (a series of nine books that he would close in 1966). That same year he returned to the United States with a Guggenheim Fellowship and achieved professional and financial stability, collaborating on research projects at the University of New Mexico and teaching in Denver, Harvard and New York. Married to Florence Hill (with whom he had two more children and whom he divorced in 1963), in 1947 (the year he published El rey y la reina) he was awarded the chair of Spanish Literature at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. There he had as a student Lucia Berlin, the writer who would become famous in 2015, eleven years after her death, when her critically acclaimed collection of short stories, Manual for Cleaning Women, topped the bestseller lists around the world.

A naturalised American citizen, in the 1950s, in the midst of Senator McCarthy’s witch-hunt, he was forced to sign an anti-communist manifesto to keep his job. In those years he wrote titles such as El verdugo afable, Los cinco libros de Ariadna and Bizancio, followed by many others, including La tesis de Nancy (which was to have several sequels), Carolus Rex, La aventura equinoccial de Lope de Aguirre, El bandido adolescente, Tres novelas teresianas, Criaturas saturnianas and books of short stories such as La llave y otras narraciones, Las gallinas de Cervantes y otros cuentos and Relatos fronterizos. He also rewrites and updates some of his works and maintains an intense correspondence with the writer Carmen Laforet.

Between 1965 and 1971 he taught at the University of Southern California in San Diego and his work began to be disseminated in Spain. He won the Planeta Prize in 1969 (with En la vida de Ignacio Morell), the same year that the amnesty decreed by the dictatorship allowed him to travel to Spain. He visited Aragon on more than one occasion (Saragossa, Huesca, Chalamera…) and his name was at some point mentioned as a possible candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

With asthma problems, he was in the process of recovering his Spanish nationality when a heart attack ended his life in San Diego on 16 January 1982. Before that, he had had the opportunity to sort out his memories and recover his roots in the two volumes of Solanar y lucernario aragonés (a compilation of his articles in Heraldo de Aragón, a newspaper which, like Aragón Exprés, published contributions by him) and the autobiographical novel Monte Odina. His ashes were thrown into the Pacific, as he had requested. A fitting end, surely, for someone who had led an agitated life, in a continuous search for himself and for a place in the world.

References

- Javier Barreiro (2010): “Ramón J. Sender”, en Dictionary of contemporary Aragonese writers (1021-1036). Zaragoza, DPZ. Reproducido en https://javierbarreiro.wordpress.com/2011/09/17/ramon-jose-sender/

- José Luis Cano (2001): Sender y sus criaturas. Zaragoza, Xordica.

- Francisco Carrasquer (2001): Sender en su siglo. Antología de textos críticos sobre Ramón J. Sender (ed. de Javier Barreiro). Huesca, Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses.

- Antón Castro (1993): “La patria interrumpida de Ramón J. Sender”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (218-223). Zaragoza, Gobierno de Aragón.

- José Domingo Dueñas (editor) (2001): Sender y su tiempo. Crónica de un siglo. Actas del II Congreso sobre Ramón J. Sender. Huesca, Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses.

- Jesús Vived (2002): Ramón J. Sender. Biography. Madrid, Páginas de Espuma.

- Great Aragonese Encyclopaedia on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/voz.asp?voz_id=11669

- Cervantes Virtual Centre. Exhibition “El lugar de Sender”: https://cvc.cervantes.es/actcult/sender/

Teaching activities

A huge project

Look up the meaning of the word “enormous” and some synonyms.

The Academy Dictionary is very terse. It defines the term simply as “very large”. Wordreference is more generous with synonyms: colossal, monumental, enormous, huge, immense, colossal, grandiose, gigantic, gigantic, titanic.

Since his childhood, Sender had felt the imperious need to write in order to “understand and understand himself or, at least, to alleviate the perplexity of living, driven by an obsession from which one must free oneself” (as José Domingo Dueñas explains it). His work is just that, enormous: sixty novels, fifty-nine books of short stories, fourteen collections of poems, thirteen plays, thirty books of essays or compilations of articles and thousands of newspaper columns in a multitude of titles.

Why do you think writing is so important to so many people? Is it important to you? Do you by any chance like to collect reflections, memories, thoughts, or recount your experiences in a piece of writing? Do you like to imagine stories and tell them? If you don’t, don’t you think it might be good to try? It’s a very personal thing, but maybe you’d like to share a short composition, an essay on a specific topic?

Homeland is childhood

That phrase was said by an Austrian poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, more than a hundred years ago. It is not for us to put ourselves in the head of a writer, and even less so of a personality as complex and contradictory as Ramón J. Sender’s, but the fact that he began to publish Crónica del alba, his fictionalised autobiography (“apocryphal memoirs”, as others call it) in 1942… What had happened in the last years of his life, did he still live in the same country, did he still have the same family as only six years earlier, in 1936?

As a consequence of the Civil War, Sender lost his wife, led an eventful family life, became disenchanted with ideologies that had seduced him, lost his roots when he was forced to go into exile…

In a way, Crónica del alba is a kind of therapy: by novelising his childhood, adolescence and early youth (concentrated especially in the first four novels of the Crónica del alba series, Hipógrifo violento, La Quinta Julieta and El mancebo y los héroes), he tries to recover that homeland he has lost: unable to return to Spain, to Aragón… he recognises himself, he finds himself again through those early years of life. When speaking of this writer, Antón Castro speaks of “rural childhood as a lost paradise”. In other later books he delves into more stormy times, the war, etc., and he does so in a more unhinged way, with very complex metaphors, but the first books reflect a certain innocence, albeit with a great deal of irony and hidden meaning.

Read this paragraph from Chronicle of the Dawn:

When I turned ten, I thought I had entered the age of responsibility. I moved away a bit from the street fights, the group fights. I had my own in the village. Eight or ten boys who fought under me. The fiercest opposing group was led by Colaso and its most terrible member was Carrasco, who lived in the house next to mine. It had been three months, however, since I had seen either of them. This change was due to my initiation into student life and to the fact that my family was making my private life more and more difficult every day. I had to study, and it was no longer a question of primary school, but of serious teachers who lived in the capital and to whom I had to present myself in order to establish my ability in such arduous subjects as geometry, history and Latin.

What does it suggest to you? It seems to explain the passage from one stage to another. Does it sound familiar?

In this first book of the Crónica del alba series (the one with the same title), Sender also projects his difficult relationship with his father, a stern, upright man who wanted him to study law and despised his attraction to poetry. Much later, the writer would recall: “My father thought it was a disgrace for a son to write poetry, but my mother, behind his back, asked me to read him my clumsy verses or my novels or comedies. I wrote all that. My mother would listen to me and say: ‘I have never heard anything more beautiful’.

In this novel, the author puts us on the trail of a restless, impulsive boy with the makings of a leader and a touch of rebelliousness. Some critics have even described this book as a sort of “An Aragonese Tom Sawyer”.

Have you heard of Tom Sawyer, does this book ring a bell? In any case, look for information about it: who is the author? where and when does the action take place? what is the main character like, what qualities does he have? Look for a synopsis of the plot or, why not, you could read it.

If you add to this the reading of the first Chronicle of Dawn… or at least its synopsis, you will surely be able to establish some similarities: childhood crushes, rivalries, adventure, mischief, cave exploration, treasures… imagination, in short.

Sender in the cinema, in the theatre… and even in music.

In fact, Crónica del alba was adapted for the cinema. It was shortly after the writer’s death. It was the film Valentina, directed by Antonio Betancor in 1983, and starring Anthony Quinn, Jorge Sanz and Paloma Gómez. Televisión Española was involved in its production, which is why it has been broadcast several times on the public channel.

It is part of a TVE programme, “Versión Española”, broadcast in December 2012.

In addition to this related suggestion, there could be a group viewing of the film in the classroom.

Valentina was continued in 1984, with the film 1919, which interprets the plot of El mancebo y los héroes (fourth novel in the series). It is set in a turbulent period (workers’ uprisings, repression…) in Saragossa in 1919.

Although names and dates are changed, some of the things told in 1919 are related to real historical events: the uprising in the Carmen barracks in Saragossa (January 1920). Look for information about this event: what happened, who motivated it, in what context did it take place?

Prior to the two films we have discussed, there had been some adaptations of Sender’s works into dramatic pieces for television and episodes of series. And they were followed by the premieres of

Réquiem por un campesino español (1985), directed by Francesc Betriu.

El rey y la reina (1985) by José Antonio Páramo.

Las gallinas de Cervantes (1987), by Alfredo Castellón.

In addition, other directors have found in Sender’s works fundamental pieces to undertake certain cinematographic works, such as Pilar Miró (El crimen de Cuenca, 1979) or Carlos Saura (El Dorado, 1988) based on the novels El lugar de un hombre and La aventura equinoccial by Lope de Aguirre.

These questions, and others, are dealt with in Ramón J. Sender y el cine, a book coordinated in 2001 by Alberto Sánchez and Lázaro Alexis as part of the Huesca Film Festival, in which Carmen Peña and Jesús Ferrer review the adaptations of Sender’s works to the seventh art.

Among the reasons why Sender has been such a well adapted author, Francisco Carrasquer points to his “lack of rhetoric, the linearity of the action, the extreme mobility of his style and the dramatic configuration of some of his narratives”. The relationship between the plot of these works and the first decades of the 20th century or the Civil War helps to rehabilitate the visual memory of a part of Spain’s history.

Participating in these narrative values, and with a very intense relationship with transcendental historical moments of the 20th century (specifically the Republic and the war), Réquiem por un campesino español (Requiem for a Spanish peasant) has been a very popular novel.

Among other things, it has inspired a play by the Aragonese company Teatro Che y Moche, which premiered it in 2021.

The Aragonese folk-rock group Ixo Rai! also entitled “Paco el del molino” (the protagonist of the Requiem…) one of the songs on their album Entalto (1999).

A life of the 20th century. From Morocco…

Sender was born almost with the century and lived intensely its contradictions, the moments of revolution and change, the conflict, the exile, the struggle of ideas, etcetera. A fundamental experience was his military service in Morocco between 1923 and 1925. Witness to scenes of injustice and corruption, he returned from there with his left-wing ideas strongly consolidated and with a baggage of experiences that he would transfer to Imán (1930), the novel with which he would make a name for himself on the literary scene.

Document yourself: What was going on in Morocco in those years? Why did Spain have its sway there? What other European countries were present in North Africa? Who usually went to war? What were the “quota soldiers”? Look up information about the Annual disaster, Abd-el-Krim and the Al Hoceima landing.

… into exile. The exile of Sender and other Aragonese writers

Exile is synonymous with exile (“losing one’s land”) and “expatriation” (“being left without a homeland”). In addition to Sender, other Aragonese writers had to leave Spain because of their commitment to the Republic defeated in 1939. Here are two of them, and another who left later but for similar reasons.

Fill in the gaps in the information about them:

-

- Benjamín Jarnés was born in …(a)… in the village of …(b)…. (in the district of Belchite): narrator, essayist and literary critic close to the Generation of 1927, his best known work is El profesor inútil (1926). He went into exile in …(c)…, from where he returned very ill and died in 1949.

- José Ramón Arana’s real name was …(a)…, born in Garrapinillos in 1905. He played a very prominent role in the Council of Aragon during the …(b)….. He emigrated to Mexico, where he edited the magazine Aragón. His most important work is the book of short stories …(c)…, the first edition of which dates from 1950. He returned from exile and died in 1973. He is buried in …(d)…, the village of his family.

- Ildefonso Manuel Gil, was born in …(a)…. (1912) and died in Saragossa in …(b)….. He was a poet, storyteller and translator. After the war, he was persecuted by the regime, but endured until he left for …(c)… in the 1960s. He returned in …(d)… and was very involved in Aragonese cultural life.

Solutions: 1: 1888 – Elbow – The Useless Professor – Mexico / 2: José Ruiz Borau – Civil War – The Priest of Almuniaced – Monegrillo / 3: Paniza – 2003 – United States – 1983

We recommend the book Aragón desgajado: los exilios republicanos de 1939, coordinated by Alberto Sabio, and published by the Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses and Doce Robles in 2020, compiling the contributions to a study conference held in Huesca.

Sender and his legacy

Sender and his creatures

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: