Josefa Amar y Borbón

Breaking chains, overcoming barriers

Saragossa, 1749-1833

Josefa Amar was born into a family closely linked to medicine: her maternal great-grandfather and grandfather had excelled in this field and her father, José, a professor of anatomy, was appointed physician to King Ferdinand VI (he would continue to be so under his successor Charles III). Thus, as a child, she moved to Madrid with her family. Her mother, Ignacia, was a great reader and educated woman: her sensitivity undoubtedly helped Josefa to study like her older brothers and sisters, all of whom were boys. Two Aragonese scholars living in the Spanish capital, Rafael Casalbón and Antonio Berdejo, acted as tutors to Josefa, who acquired an excellent humanistic education and learned classical languages, as well as French, English and Italian.

Life

Although her parents were cultivated people, they could not rebel against the customs and conventions deeply rooted in that society, which was still under the Ancien Régime. At the age of 23 she married the lawyer Joaquín Fuertes Piquer, nephew of the prestigious Aragonese doctor and philosopher Andrés Piquer. Shortly after the wedding, her husband was called to a post in the Court of Saragossa and the couple left Madrid. Once in the Aragonese capital, in 1775, Josefa gave birth to their son Felipe.

Joaquín Fuertes was tolerant of his wife’s cultural concerns. From the time she returned to her native city, she frequented the library of San Ildefonso, began an intense social life and began to develop her intellectual facet, in which she would stand out as an essayist and translator.

Work

The Real Sociedad Económica Aragonesa de Amigos del País (Royal Economic Society of Aragonese Friends of the Country) had just been set up in Saragossa: an entity which, in the spirit of the Enlightenment and like other similar societies in Spain, sought modernisation through the application of knowledge in economics, politics, science and the arts. Her own husband and her former mentor Antonio Berdejo (then a canon in Tarragona) would support her when in 1782 she presented to the Royal Society a translation of the Ensayo histórico-apologético de la literatura española contra las opiniones preocupadas de algunos escritores modernos italianos, which was completed with the Respuesta del Sr. Abate X. Lampillas.

This text countered a campaign that had arisen in influential European circles against Spanish culture. The brilliance of the work meant that Josefa Amar y Borbón was invited to join the RSEAAP as a member of Merit. She was the first woman in Spain to join such a body. Josefa dedicated herself to working for the Society with studies that could have a practical application, such as the translation of the Discurso sobre el problema de si corresponde a los párrocos y curas de aldea instruir a los labradores en los elementos de la economía campestre.

Feminist reference

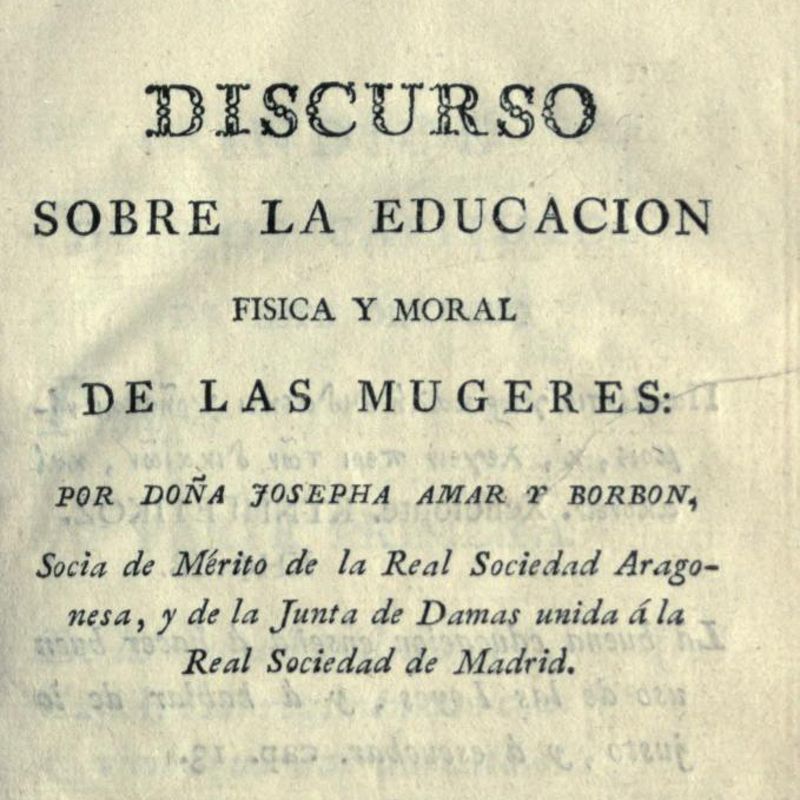

Josefa’s antecedent in the Royal Economic Society of Aragonese Friends of the Country opened the debate on the acceptance of women in its Madrid counterpart. She wrote a plea that should be taken as a foundational reference in the history of feminism: her Discurso en defensa del talento de las mujeres contributed to women’s access to the Sociedad Matritense, and led to the entry of Amar herself. Her entry was followed by another brilliant text in defence of equality: Oración gratulatoria dirigida a la Junta de Señoras de la Real Sociedad Económica de Madrid (1787). She was also appointed a member of the Royal Medical Society of Barcelona after her work Discurso sobre la educación física y moral de las mujeres (1790), in which she disseminated concepts of female hygiene and insisted on the need for women to receive instruction in grammar, geography, history, arithmetic, classical and modern languages….

But Josefa Amar also caused controversy. Some members of the Aragonese Society were annoyed by the prominence of a woman in “uncomfortable” matters and little by little she was relegated from her functions. Her husband’s illness and death removed her from social and cultural life. Since she was widowed at the age of 48, little more has been heard of her. She became involved in charitable work from the Hermandad de la Sopa in Saragossa, where she gave breakfast and medical care to the most needy. During the Napoleonic invasion, she worked in the transfer and care of the sick in the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia during the first siege of Saragossa. Retreating with relatives to Navarre, she returned to her city after the end of the war. Earlier, in 1810, her son Felipe, a civil servant in the Court of Quito, had died as a victim of the violence linked to the emancipation struggles of the Spanish colonies in America.

The trace of Josefa Amar faded away in her last years, and also after her death in 1833. Buried in the cemetery of the hospital for which she had worked, her name was shrouded in shadows. But, among them, her name and her work shine again.

References

- Poza Rodríguez (1884): Mujeres ilustres aragonesas. Zaragoza: M. Salas, pp. 189-192.

- María Victoria López-Cordón (2005): Condición femenina y razón ilustrada. Josefa Amar y Borbón. Zaragoza: PUZ.

- Pedro García Suárez (2016): Josefa Amar y Borbón: Literatura y mujer en la Ilustración Española. Madrid, Editorial Académica Española, 2016.

- Vicky Calavia: Mujeres que son tesoros. Guía didáctica. Zaragoza, Instituto Aragonés de la Mujer, 2020. https://bibliotecavirtual.aragon.es/i18n/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.cmd?path=3718032

- Esther P. Nogarol (2021): “Esa no soy yo. Josefa Amar y Borbón”, Aragón es otra historia, 1, pp. 42-43.

- Biography on Escritores en la Biblioteca Nacional. https://escritores.bne.es/authors/josefa-amar-y-borbon-1749-1833/ Very interesting page, with links to other related writers, topics, resources of interest. Link to https://diadelasescritoras.bne.es/josefa-amar-y-borbon/

- Real Academia de la Historia, Diccionario Biográfico: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/7137/josefa-amar-y-borbon

Teaching activities

An illustrious woman in every sense of the word. One ahead of her time

The Enlightenment is a cultural movement affecting 18th century Europe, where ideas based on experience and reason attempt to impose themselves on tradition dominated by religion and superstition. It is not in itself a revolutionary movement, nor does it question the established order, but it aspires to an improvement in living conditions for the whole of society, through the practical application of technical knowledge that favours the growth of the economy. According to the Enlightenment, the increase in wealth benefits society as a whole and has a bearing on general happiness (also identified with “utility”). The extension of education, conceived on the basis of confidence in scientific progress, should help to achieve these ends.

The Enlightenment is not a uniform movement: it has many manifestations and variants in different places. It laid the foundations for the liberalism of the following century, as it contained seeds that would eventually germinate against monarchical absolutism. For the time being, however, the Enlightenment went hand in hand with political power. In fact, not a few rulers adopted reformist policies led by enlightened individuals.

“Everything for the people, but without the people”. What does that phrase suggest to you? Do some research on it. Look for names of other European monarchs attracted by this enlightened spirit.

Catherine II of Russia, Gustav III of Sweden, Frederick II of Prussia, Joseph I of Portugal, among others.

The clearest example of a monarch linked to Enlightenment despotism in Spain is Charles III. Why do you think he adopted this reformist policy and let himself be advised by the Enlightenment?

Reforms are considered a good antidote to prevent revolutions because the improvement in general conditions they bring about greatly alleviates discontent. However, after the outbreak of the French Revolution (1789), monarchies became more conservative, in reaction to these subversive events that had upset the whole chessboard. In influential circles, many Enlightenment ideas, in one way or another, are considered to have been adopted by the revolutionaries. This was partly true.

The world Josefa came into contact with on her return to Saragossa as a newlywed was that of the Real Sociedad Económica Aragonesa de Amigos del País (Royal Aragonese Economic Society of Friends of the Country).

It is in this context that the figure of Josefa Amar y Borbón acquires her greatness. It must be said that, despite her advanced ideas for the time, Josefa was also indebted to her class and to the time of which she was a daughter. It is inevitable that she would sometimes be somewhat “elitist”, as this access to education was not the same for everyone. The Enlightenment has a paternalistic background (it is sponsored by the authorities themselves) and the aim is not so much a “revolutionary” social transformation as a gradual change that allows the state of affairs to be sustained.

Josefa Amar could have stayed there, but she goes a little further.

Her thinking is among the most advanced of the Enlightenment. Her erudition is not a simple collection of knowledge: she analyses, interprets the data and exercises her work with independence. She participated in the spirit of the Encyclopaedia, was Europeanist and liberal in the true sense of the word. She declared herself an enemy of extreme religiosity and advocated secularism (within the limits of what was possible: remember that, although the 18th century was the century of the Enlightenment, the Inquisition was still in operation, albeit with much less influence than in earlier times).

Enlightenment and the female condition

The Enlightenment is associated with the idea of “modernisation”. But despite the idea of progress and modernity shared by the Enlightenment, the presence of women in these fields is very marginal. Why do you think this is?

“Not content with having reserved for themselves the jobs, the honours, the benefits, in a word, everything that can encourage their application and their vigilance, men have deprived women even of the pleasure of having an enlightened understanding. They are born and brought up in absolute ignorance: those who despise them for this cause, they come to persuade themselves that they are capable of nothing else, and as if they had talent in their hands, they cultivate no other abilities than those which these can perform”.

Feminism in the French Revolution

The French Revolution that began in 1789 had very complex causes and circumstances, but many of the ideas that inspired it and others that were put on the table throughout the revolutionary process were related to the Enlightenment movement. We could say that, in this case, they were put in a shaker, shaken up, and the result was explosive (although, in time, it would be partly channelled back).

One of the most recognisable documents of this historical moment is the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Despite its “universal” approach (and with great projection in all senses), it seems that a significant part (at least 50%) of Humanity is omitted from its wording.

One paragraph reads: “Although the allegory of the Republic is represented by a female figure, this symbol did not translate into improvements for women. France, the Nation and Liberty can be painted with a woman’s body while women are deprived of basic political and civil rights”.

The song “Ay Mama” by Rigoberta Bandini must be familiar to you. You can listen to it on different platforms. In this one on Youtube, with lyrics:

In this vindication of the role of women, of values linked to motherhood, etc., the song “Sacando un pecho fuera al puro estilo Delacroix” is sung. Who is this Delacroix, what image is he referring to, and why do you think the singer uses this icon?

Liberty Leading the People, by the painter Eugène Delacroix. An iconic and universally reproduced image. Attention: it is identified with the French Revolution, but… with the Revolution of 1830 (which was another turn of the screw in the cycle of bourgeois revolutions that began in 1789).

Let us return to the 1789 scenario. It is often said that the origins of feminism as a theoretical formulation and social movement go back to the early years of the French Revolution. Despite its limitations, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was a starting point, a base of support for other initiatives such as the one that, two years later, led to the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Citizen. One of its paragraphs reads: “Woman, wake up! The bells of reason are ringing throughout the universe, recognise your rights!

Who wrote this Declaration? Research the author

Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793) also advocated the abolition of slavery, defended the separation of powers; her denunciations of Robespierre’s dictatorship led her to the guillotine.

Find information on these two other women, also linked to this historical moment and similar sensibilities: Pauline Léon and Anne-Louise Germain Necker (Madame de Staël).

Josefa Amar y Borbón would have little to envy of these women, who are today widely recognised as pioneers, intellectuals, activists, empowered women…. In fact, her most significant surviving works on feminist themes (from 1786 and 1790) predate those of Olympe de Gouges and Madame de Staël. The Aragonese thinker had a more than solid education and had read 16th-century humanists, Bacon, Leibniz and Enlightenment writers and ideologists such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and Locke. Rationalism, the division of powers, the questioning of dogma and superstition, as well as her radical denunciation of gender inequalities, make her an authority, an unequalled reference… unjustly neglected.

In the biography we said that 18th century society was still Ancien Régime. In this sense, do you think Josefa Amar was a woman ahead of her time?

Josefa’s yes

Ungrateful aftermath… So far?

Not all of Josefa Amar’s works have survived: for example, there is news of a book entitled Importancia de la instrucción que conviene dar a las mujeres (published in Saragossa in 1784), of which no copy has survived. But we can console ourselves with the survivors. Readings which constitute a great legacy, which are still relevant, which are very much up to date, and which at least, in part, do her justice.

Because posterity has not been kind to her. To begin with: her last twenty years (let us hope we are wrong) must have been sad and lonely, lived, moreover, in an adverse political climate. Why do we say this? What has happened in Spain since 1814?

After the War of Independence, Ferdinand VII returned from his cowardly exile and harshly repressed the liberalism that had manifested itself in the Constitution of Cadiz (1812). Absolutism (which was only briefly curtailed during the 1820-1823 triennium) prevailed until the death of the king (coincidentally, the same year as Josefa’s death). There was then a fierce struggle (manifested in the Carlist Wars) between an absolutism that wanted to maintain the Ancien Régime and a liberalism that, with difficulty, would gain the upper hand.

But after his death, he was forgotten. Not entirely: her impact among the enlightened people earned her a simple memorial in a short street in the centre of Saragossa and in the name of a primary school… and a curious and incomprehensible misunderstanding on the Internet, where Josefa (of whom no portraits are known during her lifetime) is matched in all the search engines with an image that is not hers, but that of a writer (Patrocinio Biedma) a hundred years later!

Fortunately, for some time now, these oversights have been compensated for by recognition of her life and work. She is not as famous as her French contemporaries, but her merits are greater. That a person who did so much for the visibility of women at such an early stage should cease to be almost invisible… it is everyone’s task, it is everyone’s task.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: