Joaquín Costa

The top man, the simple genius

Monzón, 1846 – Graus, 1911

Joaquín Costa was born into a peasant family that would soon move to Graus. His father was known as “El Cid” and, in the absence of wealth, he was a man of good judgement and popular wisdom. The eldest of eleven siblings, Joaquín was a melancholic child, not much given to games, but with a lively curiosity and intelligence and a tremendous love of reading. The countryside was not his thing, and he was sent to Huesca as a servant to a rich relative. He did not shun manual work, as a coachman, soap-maker and bricklayer, but neither did he shun study: at the General and Technical Institute he prepared himself to become a teacher and surveyor, and gave classes in Latin, Spanish, arithmetic and drawing.

Life

In 1867 he got a job as a worker at the International Exhibition in Paris. The work allowed him to breathe in the air of Europe and modernity, to write down his impressions, meticulous as he was (this would lead to his first book, Ideas apuntadas en la Exposición Universal del 1867 para España y para Huesca), and even to copy the plans for a new contraption: a velocipede. It seems that these drawings reached Huesca and the blacksmith Mariano Catalán built the first bicycle in Spain there.

On his return, he settled in Madrid, obtained his Bachiller’s degree and enrolled in Law and Philosophy and Letters. He worked as a teacher and wrote articles and translations to earn a living, with great difficulty: he completed both degrees in four years but had to wait to raise the money to be able to pay for the degrees and obtain a doctorate. Progressive and free-thinking, he came close to Krausism and the projects of Francisco Giner de los Ríos. This would cost him dearly: the prevailing political climate since 1876 was conservative, and other candidates with less merit would have preference, whether in the extraordinary prize for Philosophy and Letters (where his competitor Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo won) or in the competition for professorships and other academic posts.

Work

His ideas also became an obstacle when, having settled in Huesca as a legal officer, he was rejected by the family of the woman he loved (his father, a traditionalist, did not like him because he was a republican; his mother did not like him because he was poor). Back in Madrid, he works as a lawyer and teaches at the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, whose Boletín he directs. He recommended excursions and practical classes, contact with nature and physical education; he defended the pedagogical missions and the need for scholarships to study abroad…

Studious and hard-working to the point of exhaustion, he wrote tirelessly, took part in congresses and gave lectures on law, agriculture and tariffs. He had a relationship with Isabel Palacín, with whom he had a daughter, Pilar Antígone, in 1883, but they did not become a family. For a few years he edited the Revista de Geografía Colonial y Mercantil. He passed the competitive examination to become a notary public and set up an office first in Granada and then in Jaén. Later he returned to Graus, organised the Ribagorza Taxpayers’ League (the future Agricultural Chamber of Alto Aragón), and stood unsuccessfully in municipal elections. In 1894 he returned to Madrid as a notary. He had to deal with the shady dealings of the authorities in relation to a lawsuit with the Church over a property in the La Mancha municipality of La Solana. His involvement in this lawsuit wore him down.

Graus

Costa denounced colonial policy, the lack of investment in education, injustice… He advocated a water policy that would help to improve the economy. He thinks a lot about Spain, but also about Aragon. His thundering and powerful voice contrasts with his physical ailments (a muscular dystrophy which has afflicted him since he was young and which torments him more and more). He spoke widely at the Ateneo and other forums, became a public figure and, in times of crisis, decided to take political action: appealing to the “neutral classes”, he joined forces with others (Santiago Alba and Basilio Paraíso) to make the National Union into a party, but failed in the attempt for lack of support.

Through an extensive survey among important sectors of politics and culture, he published Oligarchy and caciquism as the current form of government in Spain, in which he revealed important keys to his thinking.

He became close to Unión Republicana, a party for which he was elected as a member of parliament in 1903. But his illness was undermining him. In 1905 he returned to Graus, to his home, from where he would not leave except for brief public interventions (for example, against the Terrorism Law of Maura’s government or at the Municipalist Assembly in Saragossa). He wrote extensively in the press, received friends such as Manuel Bescós and activists from Ribagorza; he refused to receive interested politicians who sucked up to him or sought his support.

On 8 February 1911, Costa stopped breathing. He wanted to be buried near his home, but it was decided to transfer him to the Pantheon of Illustrious Men in Madrid. From Graus to Barbastro, people took to the road to pay tribute to him. In Barbastro, they put him on the train, but when he arrived in Saragossa, hundreds of people stood up at the Arrabal station to prevent him from passing. The government saw the opportunity to avoid Republican demonstrations in the capital, and allowed Costa to stay in Aragon. He was buried in the Torrero cemetery in Saragossa. A mausoleum in the form of a temple continues to commemorate him.

References

- J. G. Cheyne (2011): Joaquín Costa, el gran desconocido. Barcelona, Ariel (1ª ed., 1972).

- Eloy Fernández Clemente (1989): Estudios sobre Joaquín Costa. Zaragoza, Universidad.

- José Luis Cano (2011): Joaquín Costa, el pundonoroso. Zaragoza, Xordica.

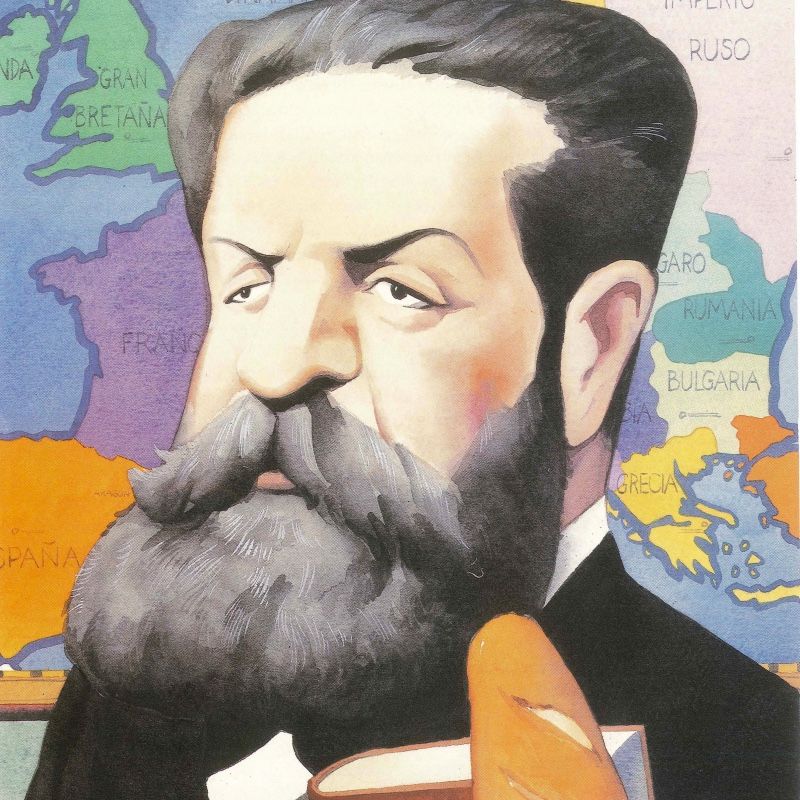

- Antón Castro (1993): “Joaquín Costa. El jabato en la niebla”, on Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (150-155). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/monograficos/biografias/joaquin_costa/default.asp

- Diccionario Biográfico Español, Real Academia de Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/5207/joaquin-costa-martinez

- AA. (2011): Joaquín Costa. El fabricante de ideas. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- AA. (2011): Joaquín Costa. el sueño de un país imposible. Una visión desde el siglo XXI del pensador aragonés. Zaragoza, Heraldo de Aragón.

Teaching activities

Historical time. Chieftaincy

The first twenty years of Joaquín Costa’s life coincided with the monarchy of Isabel II, formally “liberal”, supported by the bourgeoisie and marked by authoritarianism and corruption, which led to his dethronement. In his passage from youth to maturity, Costa witnessed the years of the Democratic Sexenio (1868-1874), with the reign of Amadeo of Savoy and the First Republic, whose innumerable obstacles led to failure.

From then on, it would live under the Bourbon Restoration in the person of Alfonso XII, the regency of his widow, María Cristina of Habsburg, and the first years of the reign of Alfonso XIII. The Constitution of 1876 provided for a parliamentary system dominated by the turn of government between liberals and conservatives, with elections directed from power and a decisive influence of the landowning classes (especially landowners and financiers), who extended their domination to all corners of the country through various networks of dependence and shared favours (“clientelism”). The caciques (people with local, regional or provincial influence) play a fundamental role in these networks, without forgetting the civil governors of the different provinces as a link between these local networks and the central government.

This is the synopsis of that book:

Caciquismo did not begin in regenerationist times, but it was then that it was coined as one of the “evils of the fatherland” that afflicted Spain at the time, with an empire defeated and its future put in doubt. Today, it is likely that some of the buffoonish forms of caciquismo – census tampering, “pucherazos”, vote-buying, dead people’s votes, “partidas de la porra” – make us smile and conclude that those times and ways are long gone. Is caciquismo a mere antiquity? The answer is only possible with the long-term vision provided by this book, whose purpose is to discover trends in the historical evolution of the phenomenon. Carmelo Romero traces with precision and irony these “geographies of influence”, complemented by abundant graphic material on the family and power structures of each historical moment. Undoubtedly, the current context has changed substantially: politicians today face other challenges and can no longer count on the submission of voters. More subtle strategies (electoral propaganda, closed lists, domination of party apparatuses, etc.) are some of the current manifestations of the prolific clientelist system.

Joaquín Costa denounced these practices, which he considered incompatible with a serious, European country. Let us read this excerpt from Oligarchy and Caciquism (1901):

[These external components are three: l ° The oligarchs (the so-called primates), the leading men or notables of each side, who form its “plana mayor”, usually resident in the centre; 2° The caciques, of first, second or higher degree, scattered throughout the territory; 3° The civil governor who serves as their organ of communication and instrument. This is what the whole artifice is basically reduced to, under the weight of which the nation groans in surrender and prostration.

Oligarchs and chieftains constitute what we usually call the ruling or governing class, distributed and pigeon-holed into parties. But even if we call them so, they are not; if they were, they would form an integral part of the nation, they would be organic representatives of it, and they are nothing but a foreign body, like a faction of foreigners who forcibly seize ministries, captaincies, telegraphs, railways, batteries and fortresses to impose taxes and collect them.

In elections (…), it is not the people, but the conservative and ruling classes, who falsify the suffrage and corrupt the system, abusing their position, their wealth, the levers of authority and the power that had been given to them to direct the masses”.

Do you think that Costa is criticising caciquismo, simply in an ad hoc manner, as bad practices, or is this criticism perhaps understood as something broader, affecting the political system? In this paragraph he does not say so openly, but do you think he could also point to deeper causes? Perhaps Costa’s criticism is more comprehensive, for example, pointing to education as a basic element? Do you think that a more educated country, with more educated and better informed citizens, is just as manipulable as a country with high illiteracy rates and less participation?

A clue to these questions can be found in one of Costa’s phrases: “To make the Spanish people free, to raise their culture through education and to create a social discipline that obliges everyone and reaches everyone”.

The turn-of-the-century crisis and the regenerationists

During the years of the Restoration, progress was made thanks to a certain openness, with more permissive laws and the arrival of universal suffrage (albeit only for men). But the last years of the 19th century were marked by a severe economic crisis (which was very marked in Spain because its productive structures had not been modernised) and a political crisis. The workers’ movement, regionalism and peripheral nationalism… also challenged the system, which had proved to be ineffective. The turning point was the defeat in the war that pitted Spain against the United States and led to the loss of its overseas colonies (Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, etc.). The so-called Disaster of 1898 was a slap in the face of reality that brought with it a moral crisis.

The Generation of ’98 was the cultural and literary expression of a rethinking of schemes… and it was in this context of crisis that regenerationism took shape, of which Joaquín Costa is considered the main representative.

Look up the term “regenerationism” in the Diccionario de la Real Academia. You will see that there are two meanings: the “historical” one, which dates from Costa’s time (end of the 19th century), is preceded by a more general definition, which can apply to any period. In fact, from time to time this term is still used in political discourses that are very different from one another. Why do you think it is used so much? Is it related to the need for “change” that is frequently mentioned, for example, before elections or in parliamentary debates? Is “regenerationism” only used when trying to criticise the opposite party? Do you think that “regenerationism” is only a political term, or does it have more projection?

Regenerationism is not a uniform ideology (perhaps that is why Costa’s attempt to turn it into a party failed). It is rather a critical attitude towards a reality that it seeks to change. Under the umbrella of “regeneration” there is room for many positions, left-wing and right-wing. It is a cross-cutting term. Regenerationism has a historical meaning, but there are also formulas and discourses that appeal to “regenerate” in other eras.

Aragonese Regenerationists

Let us go back to Costa’s time: to the passage from the 19th to the 20th century. Intellectuals and scientists have come to be considered “regenerationists” who, from their fields of knowledge, tried to contribute to improving the country’s conditions, to lift it out of backwardness. Among the Aragonese, the distinguished neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the internationally renowned paediatrician Andrés Martínez Vargas and the anthropologist Rafael Salillas have been called regenerationists, among many others (also writers, historians…). From their professional excellence, they were concerned with maintaining a public commitment, they gave their opinions, they spoke out… but there were others who intervened more consciously through openly regenerationist projects and with aims clearly linked to the territory.

Look up information about these characters and link the two columns.

- Lucas Mallada a- Promoter of the French-Spanish Exhibition

- Basilio Paraíso b- Figure of pedagogical renewal

- Santiago Vidiella c- Author of Los males de la Patria

- Domingo Gascón y Guimbao d- Founded the Boletín de Historia y Geografía del Bajo Aragón.

- Miguel Sánchez de Castro e- Scholar, director of the Miscelánea Turolense

Solutions: 1-c; 2-a; 3-d; 4-e; 5-b

Costa and Aragón

Although his life, his professional career and his fields of study went far beyond the framework of his birthplace, Joaquín Costa always transferred many of his intellectual and sentimental concerns to Aragon.

Within his professional dedication as a jurist, Costa paid much attention to Aragonese foral law, conceiving it as something closely linked to civil liberty, to custom (“customary”) and to the fueros. He maintained that “Aragon is defined by law”, as a sign of identity and as a unique contribution to the rest of the world. Proof of his commitment in this sense was his involvement in the Congress of Aragonese Jusrisconsults, whose proceedings he coordinated.

Land and water were also fundamental for someone who, through his experience and family ties, was well aware of the harshness of peasant life. He advocated the modernisation of agrarian structures, property reforms and collectivist formulas, the mechanisation of agricultural work, diversification through small industries, agronomic education, experimentation, fertilisers and new crops… and the extension of irrigation systems. All this would lead to better living conditions, in which education and culture would also play a part. Moreover, this would allow the peasants to free themselves from dependence on the caciques and from this servitude.

Complete these sentences, related to projects promoted by Joaquín Costa:

-

- The League of ………………….. of Ribagorza was later called the Agricultural Chamber of Alto ………………

- In 1899, the National Assembly of Chambers of …………….. met at ………………, from which the ………….. was created. National Chamber of Producers

- Costa proposed various hydraulic works, of which the ………… of Aragon and Catalonia was the result. After his death, the Project of …………. of Alto Aragón was created, and years later, in 1926, inspired by his message, the Confederation …………….. of the Ebro was born.

Hidden words in this order: 1: Taxpayers – Aragon; 2: Saragossa – Trade – League; 3: Canal – Irrigation – Hydrographical

For Costa, the river Ebro was “the cradle and centre of Aragonese nationality, Spain’s teacher in social matters”. The commitment and love for his land and messages of this kind have contributed to forging an image of Joaquín Costa as the maximum representative of Aragonese nationalism. Parallels have been drawn between Costa’s image, abrupt and firm, and the harshness of the Aragonese land, and many metaphors have been transferred about him, as exemplified by the epitaph written by his friend Manuel Bescós, which can be read in the mausoleum that houses his remains:

New Moses of a Spain in exodus. With the rod of his inflamed word he illuminated the fountain of living waters in the barren desert. He devised laws to lead his people to the promised land. He did not legislate.

Costa has left much trace after his passage through this world. The breadth of his discourse, the complexity of the issues he dealt with and his own contradictions (which he also had) have meant that, for more than a century, all kinds of ideologies have relied, more or less blatantly, on the figure and message of Joaquín Costa, and that he has been used politically.

In addition to condensing him into an image, Costa has also often been reduced to a few emblematic phrases: Look up phrases by Joaquín Costa and explain their meaning.

For example, “Escuela y despensa” (demanding education and economic improvement), “Doble llave al sepulcro del Cid” (asking not to waste resources in military adventures), and many more…

A monumental work

Costa said of himself that he was “a farm labourer who was an intellectual”. And Antón Castro said of him that “his head was so full of thoughts and ideas that he lived with his heart on tenterhooks, chained to the tyranny of an intelligence as disordered as it was audacious”. Joaquín Costa is often described as a “polygraph”. That means that he wrote a lot. And on many subjects, he dealt with everything. He is a pioneer in many disciplines of what today is called Social Sciences, from Law and Economics to Anthropology and Ethnography, as well as Political Science, Sociology, History, Geography, Pedagogy, Linguistics? And he did not focus on any of them. Eloy Fernández Clemente says that, if he had devoted himself exclusively to one or two of these subjects, he would undoubtedly be a world-renowned figure in them.

Joaquín Costa’s written work is enormous and unbounded. Hundreds of books, articles and speeches bear witness to his intense involvement in research, his continuous work as a disseminator and his eagerness to transmit knowledge. After his death, reeditions and compilations of his texts were made, which, with dubious criteria, often created confusion.

These are his main works (they constitute only a part of his written output, but they give an idea of the wide range of subjects in which he was interested):

- The Life of Law. Essay on customary law (1876)

- The political, civil and religious organisation of the Celtiberians (1879)

- Customary Law of Upper Aragon (1880)

- Theory of the individual and social legal fact (1880)

- Introduction to a treatise on politics taken verbatim from the proverbs, romanceros and heroic deeds of the Peninsula (1881)

- Civil Liberty and the Congress of Aragonese Jurisconsults (1883)

- Legal and Political Studies (1884)

- Spanish Popular Poetry and Celto-Hispanic Mythology and Literature (1888)

- Reorganisation of the notary’s office, the Land Registry and the Administration of Justice (1890-93)

- Iberian studies (1891-95)

- Agrarian collectivism in Spain (1897-98)

- Reconstitution and Europeanisation of Spain: programme for a national party (1900)

- Oligarchy and caciquism as the current form of government in Spain, (1901)

- Customary law and popular economy in Spain (1902)

The best monument: a School

After Joaquín Costa’s death, there were many praises (sometimes coming from politicians and writers who had not paid much attention to him during his lifetime) and monument projects. Find out where in Aragon there are statues dedicated to Joaquín Costa.

For example: Saragossa, Monzón, Tamarite, Graus

But many also said: “Let us raise a monument to Costa in our consciences”. That is to say, let us do him justice by following and spreading his teachings, reading his work… and paying homage to him in an aspect that was transcendental for him: a modern and creative pedagogy, a practical, healthy and free education. The Costa School Group was set up in Sragossa in 1929 following a popular subscription, and at the time synthesised the most advanced pedagogical methods. That and the environmental sensitivity condensed in initiatives such as the Tree Festival… are the real tributes to Joaquín Costa. At least, the ones that would have left him most satisfied.

The material legacy

The Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses (Diputación de Huesca) houses the Centro de Estudios Joaquín Costa, heir to the Foundation dedicated to his memory. This Centre publishes the Joaquín Costa Journal (formerly the Annals of the Joaquín Costa Foundation). The headquarters of the IEA in the city of Huesca also dedicates a part of its headquarters to the Espacio Costa.

A short visit to the Espacio Costa in person would also be very welcome.

Joaquín Costa, the pundonorous

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: