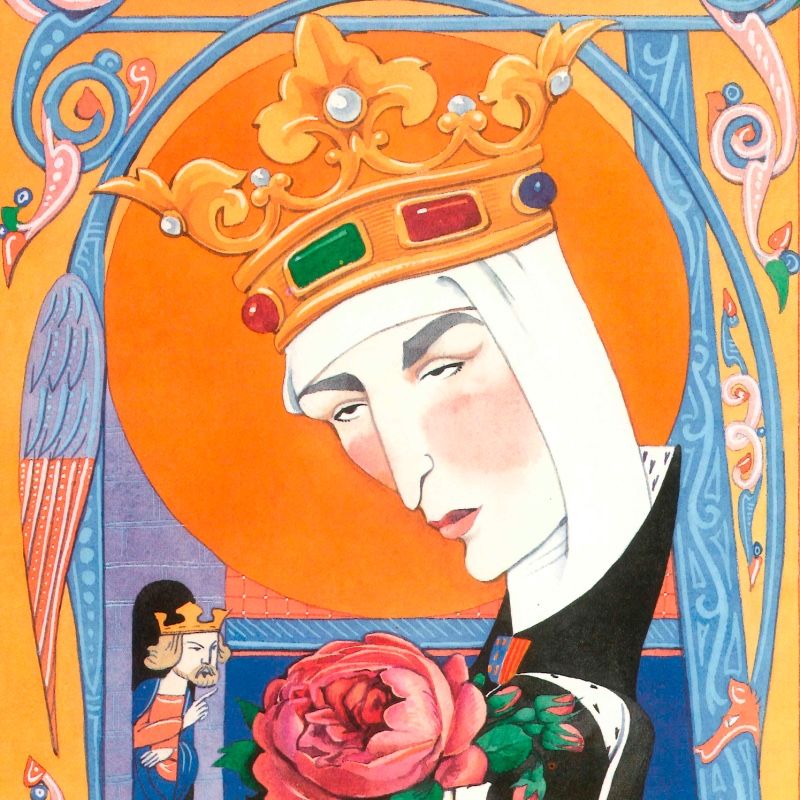

Isabel de Portugal

The peacemaker, the generous one, the patient one

Saragossa, 1271 – Estremoz, Portugal, 1336

Isabel was born in the palace of the Aljafería, the residence of Christian kings as it had previously been for Moors. She was the daughter of Peter III of Aragon and Constance of Sicily, who epitomised the Mediterranean vocation of the Crown.

Her father’s reign was tormented by external conflicts with France and with the Pope, who excommunicated him. He also had to deal with internal problems with the Aragonese nobility, who wrested the Privilege General from him, and to resolve disagreements within his own family (his brother James II of Mallorca and his nephew Sancho IV of Castile, who were lukewarm in their external support). The unpleasantness and hustle and bustle brought him to his grave at the age of 45.

By then, in 1285, the devout and generous-hearted Isabel had already been sacrificed to geopolitics through an arranged marriage. She was queen consort of Portugal through her marriage to King Dionís I, a cultured, resolute man of great personality who, although he did not conform much to Catholic morals, always tolerated his wife’s pious character and absolute devotion to the underprivileged.

The Queen of Portugal devoted many hours and funds to the care of the sick, the elderly and beggars, ordered the construction of convents, hospitals, schools and orphanages… and put up with her husband’s infidelities without fuss, which resulted in a few natural children. Meanwhile, she gave birth to Constanza (who was to become queen of Castile) and Alfonso, who was to succeed her father as king of Portugal… not without problems. Dionis was an effective administrator, cultured, prudent and innovative, and his reign was not too troubled, but in his last years it was clouded by succession struggles that pitted his son Alfonso against one of his bastards (Alfonso Sanchez).

Isabel is known to have mediated in these disputes over the throne, even, it is said, exposing herself in the middle of the battlefield. Some versions place these events in the midst of a confrontation between father and son (and not between half-brothers, since Dionís seemed to favour the son born out of wedlock). After the death of Don Dionís in 1325 and his son’s accession to the throne, Isabel made a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and on her return she entered the convent of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra, which she herself had founded, where she took the habit of the Poor Clares and continued to finance charitable works. In her very old age, she once again played the role of peacemaker in the face of the political ambitions of her descendants: her son Alfonso of Portugal and her grandson Alfonso of Castile.

She was in this state of affairs when she died on 4 July 1336.

Miracles were attributed to her after her death. The Church beatified her in 1526 and a century later, in 1625, she was canonised by Pope Urban VIII.

References

Antón Castro (1993): “Isabel de Portugal, una alondra de piedad”, en Antón Castro y José Luis Cano, Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (pp. 42-47). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

María Pilar Queralt del Hierro (2009): La rosa de Coimbra. Barcelona: Styria. Novela.

Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabel_de_Portugal_(santa)

Teaching activities

The Miracle of the Roses, a Baroque painter and the boundaries between legend and history

Isabel seemed predestined for sainthood. She was so named in memory of her great-aunt Isabel of Hungary (canonised in 1235). And “our” Isabel is often associated with a legend also attributed to her relative.

Tradition tells us that one day the queen was carrying a large amount of money for the poor. Her husband, the king, had forbidden her to give alms and when the king asked her to show what she was carrying in her skirt, the coins had turned into a bunch of roses, thus avoiding her husband’s wrath.

Francisco de Zurbarán depicted Isabel in this guise in 1626, on the occasion of her canonisation.

(An effigy of Santa Isabel is also preserved in the old cathedral of Coimbra).

The truth is that the iconography and versions of the two Santas, the Hungarian and the Aragonese, are sometimes confused. This leaves one question in the air: where is the legend and where is the reality? The tradition of Isabel acting in secret from an irascible husband does not seem to coincide with historians’ accounts of Dionis as sympathetic (and even complicit) with Isabel’s charitable campaigns.

Search online for information about King Dionís I of Portugal: some consider him to be one of the mainstays of Portuguese modernisation and national sentiment. On what basis? There are other stories about the king’s private life. That connects with the next section.

The king and queen, the double standard

It is possible that the monarch had a tacit agreement with his wife not to object to her charitable activities, while Isabel turned a blind eye to her husband’s constant dalliances. The king, a troubadour and seducer, had many mistresses and children who then had to be “placed”. Isabel herself favoured their education and privileged support (one of them, in fact, would unsuccessfully dispute the throne with the legitimate son, Alfonso).

This extra-marital behaviour in privileged spheres is a very common occurrence throughout history, and in many periods it was considered “normal”. However, always in the same direction: the man could maintain this “double life”, but woe betide the adulterous woman! If discovered, she could be marked for life… in the best of cases.

Transposed to the present day, and beyond the affairs of kings and powerful… Do you think that today some of these double standards are maintained when it comes to dealing with sentimental and sexual matters? Is a person who has many relationships seen in the same way if they are a boy as if they are a girl?

Apart from these reflections, these things also happened because, in the spheres of power (and in other more modest spheres), marriage was a political matter. Marriages were the result of an agreement between states, a formula for reconciling interests, uniting patrimonies and influences, testing alliances with third parties… In these cases, love was the least important thing (if it appeared, it was by chance), and it was not seen as wrong that, once the formalities had been completed, the king (in this case) sought to give free rein to his instincts.

Marriage for reasons of state and this utilitarian consideration of women as a “factory of successors” were discussed in more detail in the case of Queen Petronila of Aragon. A century and a half separated Isabel from the great-grandmother of her grandfather James, but things had not changed much, nor would they change for a long time.

The royal houses, their relationships… and one conspicuous absence

Without losing the thread of “marriage and politics”, we see that in the text a number of relationships and countries from all over Europe have been cited. We add a few to make up this curious mosaic:

Isabel’s parents were Peter of Aragon and Constanza of Sicily. Her two older brothers were to become kings of Aragon (successively Alfonso III and James II). Her great-aunt Isabel of Hungary was the sister of Violante (her grandmother, married to James I). Isabel married the King of Portugal: her son Alfonso would also occupy that throne. Her other daughter, Constanza, would marry the ruler of Castile, and her grandson would reign there as Alfonso XI.

Place on a map of Europe: Aragon, Sicily, Hungary, Portugal and Castile? The remoteness of Hungary is striking, and… that France, so close to Aragon and so closely linked to its history in previous centuries, does not appear on the map.

During the 13th century, Aragon’s relations with the kingdom of France were not good. In fact, they were openly hostile: the rivalry for influence over the territories of Occitania first, then the struggles for the Mediterranean… separated the two states, despite the fact that some time ago it had been common for the first kings of Aragon to seek marriages north of the Pyrenees, despite the decisive presence of Gascons, Béarnese, etc., in the conquest of Saragossa by Alfonso the Battler, or despite the continuous flow channelled through the Camino de Santiago (Pilgrim’s Way to Santiago). The raison d’état tended to impose other relationships.

To conclude…

The feast day of Santa Isabel

The 4th of July (the date of her death) is dedicated to this Santa, who is the patron saint of the province of Saragossa. The Diputación de Zaragoza gives the name of Santa Isabel to its annual prizes awarded to entities and groups, and also to different art, narrative, plastic arts, scenic arts, audiovisual script, etc. competitions.

A girl in the Aljafería

The central courtyard of the Aljafería is known as the courtyard of Santa Isabel, in memory of the illustrious girl born within the walls of the Taifal palace. It is easy to imagine an apparently privileged child, playing in the garden, hiding among the arches and orange trees, perhaps oblivious to the role reserved for her, perhaps partly aware of that responsibility, wondering about her troubled father’s absence…

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: