Marco Valerio Marcial

Wit and contradiction, the essence of the human being

Bilbilis, 40-104

This member of a family of local notables, who studied law and declamation in Tarraco, went to Rome to pursue his career under the tutelage of Seneca. Seneca’s fall from grace under Nero’s authority left him destitute and poor, forced to take up various trades (including soldiering).

He was in his forties when his writings began to make him popular in busy, bustling Rome and to enjoy the favour of the powerful. It was the year 80 A.D. when Emperor Titus inaugurated the Flavian amphitheatre (the Colosseum) and Marcial composed the Liber Spectaculorum in a celebratory tone. The imperial protection was to continue under his successor Domitian and was a great endorsement of his literary career.

Life

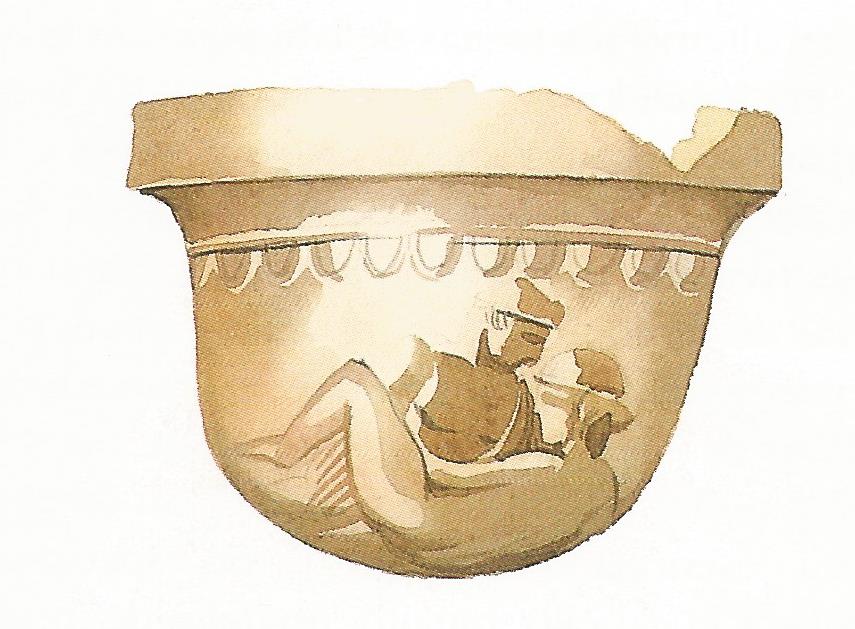

Marcial is the master of epigrammatic poetry, a genre characterised by brevity and wit. His life’s work, compiled in fifteen books, are the Epigrams: some fifteen hundred short, incisive texts, exercises in precision and wit with motifs that are often festive, sometimes dedicatory and elegiac (a genre in which he displayed enormous sensitivity) and, above all, satirical.

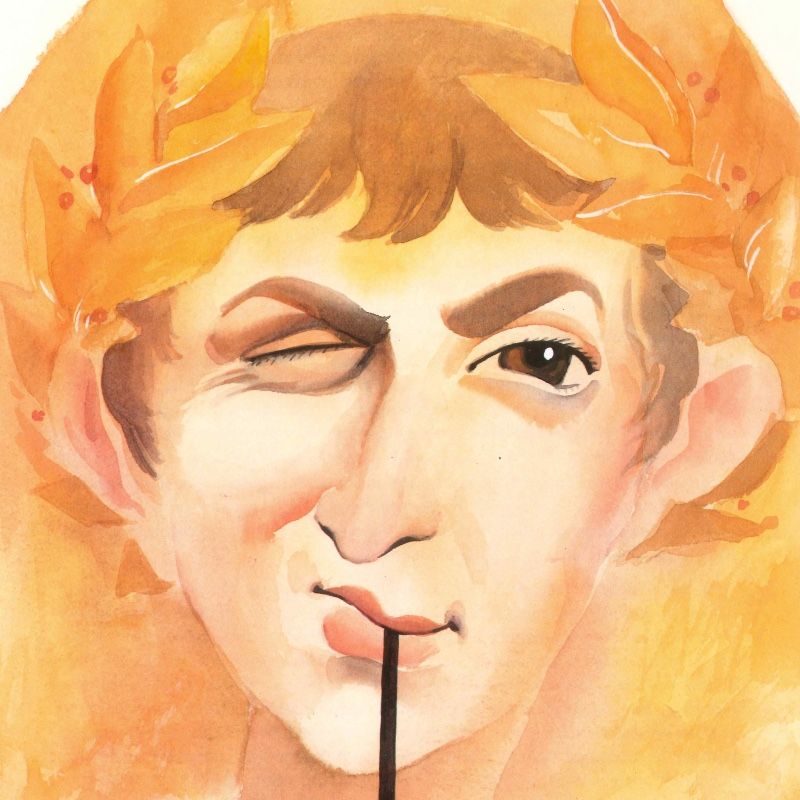

Marcial portrays with singular mastery the miseries and the grandeur of the vital and cosmopolitan city of Rome: an unbridled and unjust society that he knew to perfection. Far from narrating heroic deeds and seconding rhetorical genres, the Bilbilis man criticises hypocrisy, reflects on the human condition and its contradictions… and flatters whoever it suits him. Antón Castro describes him as “servile and ingratiating to the lords” and “sarcastic and procacious with the immoral and the cretins”. But – Castro adds – Marcial does so through a poetry defined by simplicity, spontaneity, precision and elegance, the Hispanic-Roman “knows himself to be a moralist and his vocation is to restore a humanist vision rather than destroying a reputation”.

Work

Marcial became friend of writers such as Plinio the Younger, Juvenal and Quintiliano. Yet he finds a social life of which he is a part empty; he has properties and a slave service; he enjoys notoriety in the cultural circles of Rome (he is plagiarised, and that gives an idea of his success), but he still complains, making himself seem more wretched and needy than he is. Marcial has a cantankerous attitude: he complains about how expensive life is, about the disadvantages of the big city, about the monotony and servitude of seeking out patrons and having to suck up to them in walks, conversations, baths and dinners. Transitioning from the purely lyrical to the obscene, from the dignified to the lowly… he likes to abound in paradox: “My pages are naughty, but my life is honest”.

Bilbilis

This grumpy character is one of the keys to reading his work, in which we can also detect a certain rhetorical nostalgia for his idealised homeland, to which he would return. The decision would become firm at the end of the century, when the winds of power changed direction and the Flavian dynasty was succeeded by the reigns of Nerva and Trajano. Marcial loses the imperial favours and, before he is further compromised, in his middle age and with the support of his admirer Marcela, a local landowner, he sets out to return to Bilbilis.

Irene Vallejo recreates Marcial’s return to his homeland, seeing the solitary Monte Cayo, meeting again the Jalón, and summarises his feelings: “Under the calm sky of Celtiberia, friend Marcial, you will sleep soundly (…). [Thanks to your benefactress Marcela], you will finally escape the threat of misery, which never quite left you in Rome”. The writer from Saragossa also summarises her contradictions: “You will finally know calm, but you will stop writing. On a full stomach, your rage will subside and you will leave behind your disguise as a terrible child (…). When you were in Rome, you were irritated by the artificial life and hypocrisy you observed around you. You were fed up with flattering the powerful. Then nostalgia dictated poems in which you listed the harsh names of your homeland. Well, now you are back in your little paradise of peace and quiet. Soon you will begin to grumble, mumbling your longing for the meetings, the theatres, the libraries of Rome, the sharpness of your social circle, the pleasures and bustle of the capital; in short, all that you have left for the sake of tranquillity”.

On his death, Plinio the Younger said of him: “Marcial was a witty, sharp and scathing man; in everything he wrote he put much salt, much gall and no less candour”.

Dagger

A dagger with a small circle on its curved blade. This one was tempered red-hot by the Jalón with its icy waters.

Teaching activities

The setting and context of the Epigrams

Search the internet for information about the emperors who ruled Rome during the approximate years of Marcial’s stay in the capital of the Empire (65 to 100 AD): were they all from the same dynasty? Are there any episodes that stand out for you in any of them? How did they accede to the throne and how did they die? In the text other characters are mentioned: some of them are Hispanic-Roman like Marcial: Seneca, Quintiliano (also the emperor Trajano). Find out about their biographies.

Suggestions

Historia de Roma, by Indro Montanelli

It is a classic with many reprints, written in a pleasant and light-hearted style. You can look for its descriptions of the daily life in Rome during the imperial era, the hustle and bustle, the little miseries (and some greatness) that gather in that city… It will allow you to better recognise the atmosphere that Marcial lived in and portrayed. And, be warned, it will amuse you.

Meet the Romans (BBC, 2012), by Mary Beard

This English specialist in the classical world (and superb communicator) describes in three episodes the daily life in the city of Rome, paying special attention to less favoured sectors, and with a large presence of women.

Marco Valerio Marcial: Epigramas. Full version of Second edition

Click on the following button to access the book published by the Institución Fernando el Católico (1986), with text, introduction and notes by José Guillén and revised by Fidel Argudo. It contains the Epigrams of Marco Valerio Marcial. Take a look at it and find out more about the consideration of women in Roman times.

The gender issue

The role of women in Roman times is a subject to be taken into account. Marcial, a child of his time, does not exactly come out of this situation with flying colours. His invective, sometimes foul, towards women who form part of the worldly universe (the shopkeeper, the prostitute, etc.) in which Marcial participates, is striking. But he is also delicate in his description of beauty and goodness (more often than not personified in the feminine) and in his praise of the virtues of the woman or girl mourned in some of the elegies. You can look up some of these references in the two pdfs you have downloaded containing the Epigrams.

In the references we quote (such as the brief biography of Antón Castro) there are some allusions to his private life and his relationship with women. And it is very striking that his return to Bilbilis was very much conditioned by his admiration for Marcela. Look for more information on all this.

“Marcial, el peregrino en su patria”, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano

The critique of customs

At times, women are the “victims” of a hidden meaning which, in a certain sense, has no gender and is universal (it also crosses epochs, and in this sense, many of Marcial’s texts retain all their relevance). The denunciation of vices such as presumption: “You are beautiful, we know; and young, it is true; and rich, well, who can deny it? But when you praise yourself, Fabula, too much, you are neither rich nor fair nor young” (Epigrams, I, LXIV). This message would be tantamount to “Tell me what you boast of and I will tell you what you lack”, and forms part of the criticism of customs and moralism displayed by the Bilbilitan.

Irony in the face of picaresque

For example, to the innkeeper who sells watery wine he dedicates this sentence: “The grape harvest is soaked by the continuous rains; even if you want to, innkeeper, you cannot sell pure wine” (I, LVI).

Nor does he spare sarcasm towards plagiarists and (in this case) “interpreters” of his work: “The book you recite, Fidentino, is mine; but when you recite it badly, it begins to be yours” (I, XXXVIII). In times when intellectual property and copyright were not easy matters to defend, Marcial claimed the integrity of his creations. Another example of timeliness.

The sardonic comment, not without a certain finesse

“Zoilo, why do you dirty the bath by washing your ass? To make it dirtier, immerse your head, Zoilo” (II, LXII). To good Zoilo he gives his opinion on the quality of his thoughts (he puts them on a par with shit). There is no need for further comment. Today we are talking about slaps and trolls, but… as you see, nothing is new. Marcial could be hurtful, but never toxic (or could he? What do you think?).

Search among the hundreds of Epigrams, three that seem current to you, that catch your attention, reflections that you share or think are relevant today. In this downloadable edition there are many elements and helpful notes, which make it much easier to understand.

The return to the origin: closing the circle on the banks of the Jalón River

In the Epigrams Marcial speaks a great deal about the homeland he abandoned in his youth, and to which he will eventually return. He idealises it from a distance.

Our writer was born in a Celtiberia which a couple of centuries earlier had burned in rebellion against the Roman invader. A country that had already spent decades under the pacification imposed by the victor (that was the Pax Romana), that under that rule prospered economically and that was incorporated into the Roman world (remember what we mentioned in the first paragraph).

Perhaps you can find news of Roman vestiges in your locality. Do some research. If there is a recognisable Roman past, is it in a museum or on display in some way?

The validity of Martial

In short, posterity has treated this Bilbilitan well. Humanists of the 16th century, Latinists, scholars and moralists, the master of baroque conceptualism Baltasar Gracián (a fellow countryman of his, by the way), the enlightened Juan de Iriarte, among many others, and even more contemporary researchers have studied and commented on him.

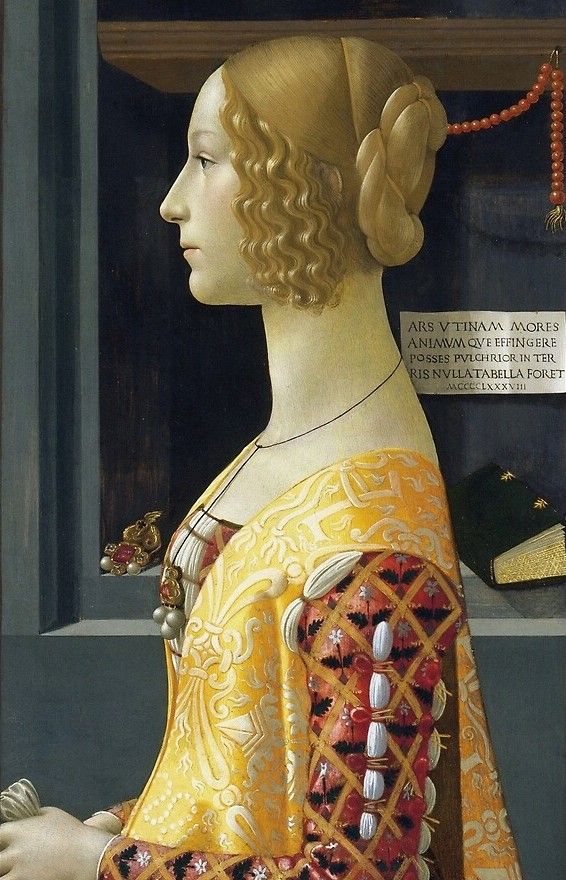

If you look at the work, in the background of the scene, you can see a Latin inscription which, translated, reads: “Art, if only you could capture the conduct and the spirit, there would be no more beautiful painting on earth”. This is yet another example of the profound lyricism, interspersed with more prosaic phrases, that Marco Valerio Marcial gave us.

Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni (1488), Domenico Ghirlandaio

Marcial el travieso

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: