Conde de Aranda

An enlightened man in the service of the king

Siétamo, 1719 – Épila, 1798

Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea was born in 1719 and spent his early years in his small home town of Siétamo, educated by Jesuit teachers. After the death of his elder brother, he became the first-born son of his family, a member of the high nobility, and when his father was posted as an army officer to northern Italy, he, aged nine, accompanied him. The Treaty of Utrecht had ended the War of Succession and brought a new dynasty, the Bourbons, to the Spanish throne, although it had ceded Spanish territories on the Italian peninsula to Austria, which Philip V’s second wife, Isabella of Farnese, wanted to recover for her sons to reign over.

In Bologna and Parma Peter Paul continued his education, again under the guidance of the Jesuits. But at the age of seventeen he abandoned his studies to take up arms. He had always wanted to be a soldier, like his father. He took part in successive battles against the Austrians and, given his courage and skill, at the age of 21 he was already wearing the stripes of colonel.

In 1742 his father died and he inherited his possessions and titles, including that of 10th Count of Aranda, by which he is known. A year later, in the battle of Campo Santo, he was seriously wounded. He did not abandon his fight against the Austrians until the Peace of Aachen was signed in 1748. By then he was a field marshal.

He took advantage of the period of peace to travel around France, Belgium and Central Europe, where the ideas of the Enlightenment, a cultural movement that defended the primacy of knowledge and reason as the engine of progress, were gaining ground. He made contact with the Parisian encyclopaedists, studied military tactics in Prussia, from where he took the Royal March that would later become the anthem of Spain, and in Saxony he visited the Meissen porcelain factories to imitate their working techniques in the Alcora pottery factory in the province of Castellón, founded by his father.

In 1755 he was appointed Spanish ambassador to Portugal, the country of birth of Queen Bárbara de Braganza, thus beginning his diplomatic career. He did not stay long in Lisbon, which was devastated by an earthquake. He asked to be relieved of his duties and on his return he was entrusted with reorganising the artillery and engineering corps of the Spanish army, despite the resistance of some senior commanders.

When Charles III came to the throne, he chose him as ambassador to Poland and Saxony, from where he had to return in haste to take command of the Spanish army that was fighting the Portuguese army in the Seven Years’ War. Although the outcome of the fighting was not very successful, at the end of the conflict Aranda was appointed captain general and governor of the kingdom of Valencia.

In 1766, poor harvests and the rise in the price of bread led to serious disturbances that were exploited to their own advantage by those opposed to the reforms promoted by Charles III’s advisors. This popular uprising, known as the “mutiny of Esquilache”, named after one of the monarch’s foreign ministers, endangered the crown. In order to bring order, the sovereign called in his most capable military officer, the Count of Aranda. He put down the revolts and was subsequently appointed president of the Council of Castile.

From this position, the most important in the government after the king, he consolidated royal authority and continued with Enlightenment policies. During his term of office, the privileges of the Church were reduced and the expulsion of the Jesuits, one of the pressure groups opposed to the changes, was decreed, which led some of his enemies to call him anti-Catholic. With the collaboration of other Aragonese, what some historians have called “the Aragonese party”, he tried to clean up the economy and modernise the country. He ordered the first census in Spain, drafted laws to increase agricultural and commercial prosperity, supported the development of the Royal Factories and the construction of the Imperial Canal and the Manzanares Canal, turned Madrid into a renovated, clean and monumental capital, on a par with other European capitals, and also undertook improvements in the cultural and artistic fields.

A firm believer in aristocratic principles, his disagreements with other ministers and with the monarch himself led to his being relieved of the presidency of the Council of Castile and sent as ambassador to Paris in 1773. In France he resumed his contact with enlightened thinkers and took part in the peace negotiations with England that led to the independence of the United States, which he saw as a dangerous precedent for the future of Spain’s possessions in America. He regained Menorca and Florida for Spain from the English. However, he did not succeed with Gibraltar.

With the accession of Charles IV to the throne, the Count of Aranda regained a privileged position at the Madrid court. He fought to prevent the French Revolution from spreading to Spain, but he opposed a war for which the Spanish army was not prepared. His confrontation with Manuel Godoy, a protégé of the monarchs, resulted in his dismissal, banishment and imprisonment, until he was allowed to retire to his possessions in Épila in 1795. There, secluded, he devoted himself to administering his lands and collaborating with the Real Sociedad Económica Aragonesa de Amigos del País, which he had helped to create, until his death. After decades of public service, this distinguished military man, diplomat and politician, obsessed with the betterment of his nation and its inhabitants, was buried by his own wish in the monastery of San Juan de la Peña, the pantheon of the kings of Aragon, to whom he was related.

References

- María Dolores Albiac (1998): El conde de Aranda. Los laberintos del poder. Zaragoza: CAI.

- José Luis Cano (1998): El gran Conde de Aranda. Zaragoza: Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “La leyenda negra del Conde de Aranda”, en Antón Castro y José Luis Cano, Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (pp. 114-119). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Eloy Fernández Clemente (2004): Estudios sobre la Ilustración aragonesa. Zaragoza: IFC.

- Rafael Olaechea y José Antonio Ferrer Benimeli (1998): El conde de Aranda (mito y realidad). Huesca: DPH [1ª ed., 1978, Zaragoza: Librería General].

- Pedro J. Pérez Correas (2002): La huella del conde de Aranda en Aragón, Zaragoza.

- Pedro J. Pérez Correas (2013): 1794, el destierro del conde de Aranda. Sus memorias. Zaragoza.

- Arturo Pérez Reverte (2015): Hombres buenos (novela). Madrid: Alfaguara.

- AA. (2000): El conde de Aranda y su tiempo. Zaragoza: IFC.

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conde_de_Aranda

Teaching activities

The Count of Aranda, a military man by vocation

Read and comment on the following text, with curious facts about the importance of the Count of Aranda in the organisation of the Spanish army. Observe how some of the ideas of this enlightened Aragonese has survived to the present day.

The 10th Count of Aranda, born in Siétamo in 1719, which is now three centuries ago, was a politician, diplomat, great agricultural landowner, industrial entrepreneur, scholar and polyglot, patron and philanthropist. But, above all, he was and felt himself to be a military man. Probably one of the greatest frustrations of his life was that the Crown did not allow him to act as a competent war chief, which he was, on numerous occasions. So much so that he even abandoned his innate arrogance to beg His Catholic Majesty to agree to entrust him with some campaigns. He rarely succeeded. Surprisingly, one might say, because his actions were successes of organisation and demonstrations of right understanding of the often complicated circumstances of war.

At the age of 17, when he was using the title of Duke of Almazán – a secondary title in his family – he ran away without permission from the Italian Jesuit school where he was being educated – his father, the 9th Count, had a military command in Italy – and enlisted in the Spanish army in Italy. A high-born nobleman with aptitude had a clear path into the military. He immediately became captain of the grenadiers – a distinguished and well-trained troop, which was required to have special conditions of strength, presence, agility and honesty – in the regiment commanded and supported by his father. Incidentally, that unit still exists: it was then called Castilla and today it is called the King’s Immemorial No. 1. Its origins date back to the 13th century and, logically, it heads the list of the current Spanish Infantry regiments.

He was immediately (1740) appointed colonel of Infantry by Philip V, which qualified him to take charge of a regiment. On 8 February 1743 he took part in a bloody battle in the War of the Austrian Succession, a conflagration between great powers fought on three continents, in which Prussia, Spain and France fought against Austria, Russia and England. In the Lombard village of Campo Santo he had a severe, almost lethal ordeal. He lay inert, apparently dead among corpses, until he was found the next day. In addition to a convalescence that did not deter him from returning to battle, his courage and further wounds suffered in subsequent battles earned him promotion to brigadier.

But as an artilleryman – a technically demanding branch of warfare with a select staff – by training and vocation, and with proven courage in combat, he was hardly able to demonstrate his recognised abilities in logistical organisation and command of operations. An exception was a Spanish-French war against Portugal and England (1762), in which he had to replace, after months of fighting, an incompetent and decrepit commander, changing the course of the campaign for the better.

Defence policy

Aranda was a remarkable manager of resources in general, and of military resources in particular. As an ambassador with vast international experience, he knew the value of a country’s military capacity. He wrote against enemy propaganda that misrepresented the size and capacity of Spanish troops, and angrily replied to a libel that assigned the Crown three regiments of Infantry when there were thirty-two, not counting those in America, “as well disciplined as those of the army of Europe”. He knew that ridiculing this power damaged Spanish policy, which was to support the American rebels, seek the recovery of Gibraltar and favour Spain’s vast lands in North America.

Charles III, aware of the shortcomings of his army, formed a commission headed by a captain general. Work included the drafting of new ordinances, but was interrupted. Aranda had been captain general since 1763 and, in 1767, the king commissioned him to take up the task again, which he completed successfully. The quality of the text made it last until Juan Carlos I commissioned General Gutiérrez Mellado to renew it in 1978. The text was revised in 2007, and an example of its success is the paragraph defining the figure of the corporal:

As the soldier’s or sailor’s most immediate boss, he will make himself loved and respected by him; he will never conceal from him any lack of subordination; he will instil in him a love of service and great accuracy in the performance of his duties; he will be firm in command, gracious in what he can and will be restrained in his attitude and words even when sanctioning or reprimanding.

Compare the reader with the 1767 text:

As the soldier’s most immediate commander, he will make himself loved and respected by the soldier, he will never conceal from him the faults of subordination. He will instil in those of his squadron a love of their trade and a great deal of accuracy in the performance of their duties. He will be firm in command, gracious in what he can, he will punish without anger and will be measured in his words, even when he reproaches.

An astonishing coincidence, especially considering that, in the old text, the king spoke in the first person. Even so, hardly anything had to be changed, such was his clever conception. Aranda, as on other occasions, had made up for the deficiencies with tireless zeal.

(Source: https://www.heraldo.es/noticias/opinion/2019/08/18/aranda-militar-1330191.html?autoref=true Aranda Militar by Guillermo Fatás)

The Conde Aranda and Carlos III

The Conde Aranda and Carlos III

Look up information and explain what this form of government consists of.

Which European monarchs are considered enlightened in the 18th century?

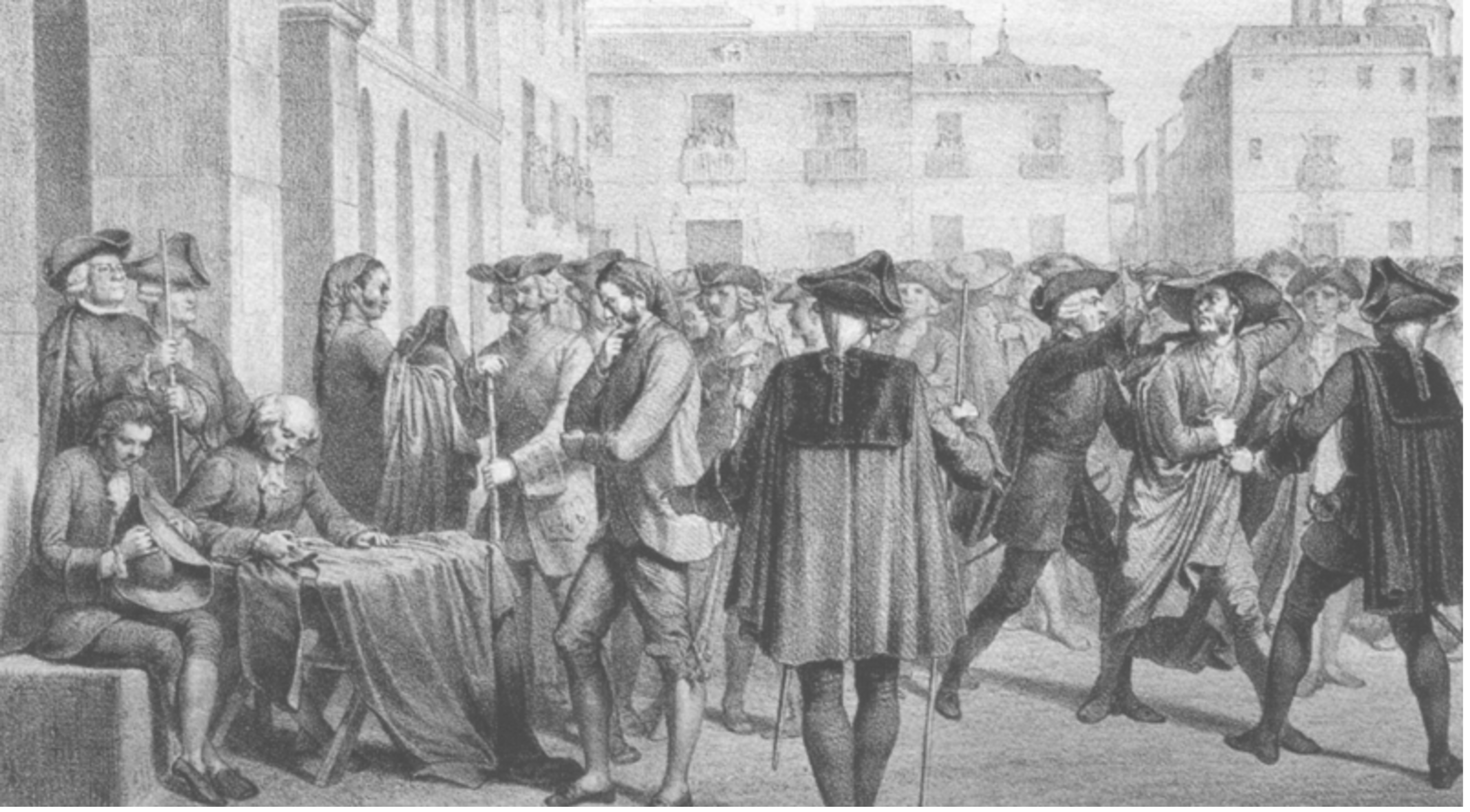

The image illustrates the problems caused by some of the reforms carried out on traditional dress as a result of Carlos III’s reformism, in this case the shortening of the cloaks and the sewing on of the hat brims.

Were these clothing reforms the only causes of the so-called Motín de Esquilache, what other events provoked the revolts throughout the country? Find out on the internet what the Bread Riot of Saragossa consisted of, when did it take place, why, how did it end, and do you think it is related to the Esquilache Riot?

After the Esquilache Mutiny (1766), Charles III summoned the Count of Aranda to Madrid and appointed him governor of the Council of Castile, a position from which he initiated the process that would end with the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, under the accusation of acting against the king and organising mutinies.

Why do you think the Jesuits were actually expelled from the country? Who controlled secondary and higher education in Spain at the beginning of the 18th century? What were the consequences of this control? Were the Jesuits expelled only from Spain or also from other countries? What were the consequences for the Spanish dominions in America? Find out on the internet what the Jesuit reductions in Paraguay were and what happened to them after the expulsion of the Jesuits.

During his seven years as head of the Council of Castile, he established a reformist policy based on the principles of the Enlightenment, which won the praise of Voltaire himself.

He undertook many other tasks of the most varied characteristics: he enacted laws in favour of mining, shipping and trade; he promoted the urbanisation of Madrid (division into neighbourhoods, construction of the Paseo del Prado) and other large cities, and organised balls and other entertainments; he made the numerous unemployed clergymen leave the capital or those who were away from their place of residence; he created centres of culture with free education and improved the universities, placing them under State control and providing them with new study plans…

What actions in line with Enlightenment thinking did Aranda take as head of the Council of Castile? Who was Voltaire?

The intrigues of his enemies and the enmity of the king led to his downfall in 1773 and his being sent to Paris as a diplomat in order to remove him from the Court. However, it was an important post, and from it he dealt with Spanish foreign policy, especially the Spanish dominions in America.

Read Arturo Pérez Reverte’s novel Good Men: What role does the Count of Aranda play in it? What do you know about the Encyclopaedia, which was published in France in the 18th century? What consequences did its publication have? Why do you think some people thought it was opposed to the Bible?

Travelling in Europe

In his biography we read that the Conde de Aranda travelled throughout his life all over Europe. During his childhood and early youth he travelled around Italy with his father. Later, between 1748 and 1755 he made an instructive journey through France and Central Europe, which allowed him to observe the advances of the Enlightenment and to have a modern view of the army, industries, education, etc. Subsequently, he was ambassador to several countries: Portugal, Poland and France.

Connect the Conde of Aranda’s travels with his activities.

| 1. Prussia Meet Frederick the Great, one of the great political figures of the time. | a) Short stay after the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 | |

| 2. Saxony Get to know the porcelain factories in Meissen | b) War between Spain and Portugal as part of the Seven Years’ War, which pitted almost all the powers of the time against each other between 1756 and 1763. | |

| 3. Lisbon Ambassador in Lisbon | c) Personal intervention in the Peace Treaty of Versailles (1783) between Spain and England. | |

| 4. Poland and Saxony Ambassador to Poland | d) Study the military tactics of the Prussian army. | |

| 5. Portugal Commander of the Spanish Army | e) Ambassador Extraordinary to the King of Poland and Elector of Saxony August III, father-in-law of Carlos III. During his stay, the Family Pact was signed in 1761. | |

| 6. Paris Spanish Ambassador to France 1773 – 1787 |

f) He learns new methods to improve his earthenware and porcelain factory in Alcora. |

1-d, 2-f, 3-a, 4-e, 5-b, 6-c

Offices and kings

It links the kings with the positions held (and episodes experienced) by the Conde de Aranda with each of them.

| Felipe V | a) 1766 – 1773 President of the Council of Castile. |

|

| b) 1756 Director General of Artillerymen and Engineers and Colonel, Artillery Regiment. |

||

| Fernando VI | c) 1761 – 1763 War between Spain and Portugal. He takes command of the Spanish army in Portugal. |

|

| d) 1755 Ambassador Extraordinary in Lisbon. |

||

| e) 1793 – 1795 Banishment in Jaén. |

||

| Carlos III | f) 1763 – 1766 Captain General of the Kingdoms of Valencia and Murcia, Governor of the Kingdom of Valencia and President of its Audiencia. |

|

| g) 1773 – 1787 Spanish Ambassador to France. |

||

| h) 1760 – 1761 Ambassador Extraordinary to Poland. |

||

| Carlos IV | i) 1741 – 1748 Fighting in the wars in Italy against the Austrians |

|

| j) 1792 – 1793 Fighting in the wars in Italy against the Austrians |

Felipe V: i

Fernando VI: b – d

Carlos III: a – c – f – g – h

Carlos IV: e – j

The great Conde de Aranda

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: