Agustina of Aragón

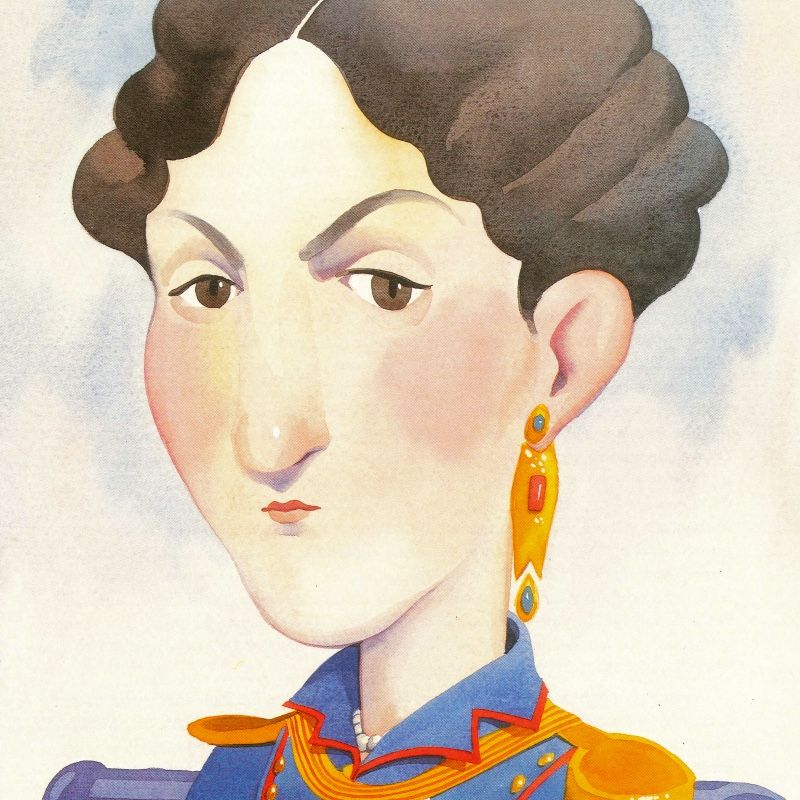

The woman, the myth

Barcelona, 1786 – Ceuta, 1851

We are going to share with you the effort to identify a woman of flesh and blood, with life, joys, sorrows and feelings… separating her from the image that has been projected of her for a long time, sometimes used as a symbol of patriotic values. We will try to distinguish the PERSON from the CHARACTER: to capture and transmit her life beyond the myth that this woman has become for posterity. With Agustina, moreover, we will see that, even though she was not born in Aragon, the strength of this image is so powerful, the link with this land and its people is so intense, she represents in such a lively way other women (who are indeed Aragonese by birth)… that we include her as an illustrious Aragonese woman with full merit.

Life

Agustina Zaragoza Domènech was born in March 1786 into a humble family of manual workers in the Ribera district of Barcelona. Her parents, Pedro and Raimunda, came from the small Lleida village of Fulleda, where the girl (who had been baptised in the Barcelona church of Santa Maria del Mar) apparently spent part of her childhood. At the age of seventeen she married Juan Roca, an artillery corporal whom she would accompany on his postings (Mahón among them).

Back on the Peninsula, the French invasion of May 1808 took place. Once Barcelona was taken by the Napoleonic troops, her husband, promoted to sergeant, was sent to fight in the Bruch (he would later fight in the area of Belchite), and Agustina, with her little Juan, marched to Saragossa. On 15 June, Lefebvre’s troops appeared at the gates of the city and began an attack which, after fierce resistance and having been forced to reorganise after the defeat at Bailén, they abandoned in mid-August. It is in this first siege, which was thwarted by the invaders, that the young Catalan woman’s gesture is situated. Apparently, helping to supply the defenders in the Portillo area, she snatched a fuse from the hands of a dying artilleryman and lit a 24-pounder cannon, repelling the assault and the attackers retreating. It is said that General Palafox witnessed the scene and granted her the post of artillerywoman, with the corresponding pay, which Agustina would earn by becoming a sergeant.

On 21 December, French troops once again laid siege to Saragossa. This time in a much more determined manner. Agustina continued to fight alongside Casta Álvarez or Manuela Sancho, under Sangenis or Renovales, with the squadrons of Numancia or with the volunteers of Aragón, on the walls and outside them… until the plague removed her from the front line. When the city capitulated, she was taken prisoner and sent to France with her five-year-old son. Amidst hardship, illness, fatigue and hunger, the child died on reaching the town of Ólvega in Soria and she managed to escape through Navarre until she reached Teruel, where the Junta of Aragon allowed her to go to Seville. There, the Central Junta recognised her merits and promoted him to the rank of second lieutenant. In Cadiz she met General Wellington but felt she had to return to combat.

Heroine

At the end of 1810 she was serving in a battery in the defence of Tortosa where, once again, she was captured by the French and, once again on the run, she is known to have taken part as an artillerywoman in the battle of Vitoria in 1813. When the war was over, she joined her husband in Saragossa, where she learned that the king had granted her, among other honours, a bonus that she would not stop receiving until the end of her days. The couple returned to Barcelona, where in 1818 Juan was born, named after his brother who had died a few years earlier. Agustina’s husband contracted tuberculosis and died in 1823. At the age of 37, Agustina was widowed and in less than a year she remarried the doctor from Almería, Juan Cobos, with whom she lived in Valencia and with whom she had a daughter, Carlota.

Shortly afterwards the family moved to Seville, where Agustina’s son studied medicine, which he practised until his death in 1885. In 1847, Carlota married a soldier stationed in Ceuta, and Agustina, who had distanced herself from her husband since his decision to embrace the Carlist cause, decided to move to the North African city with her daughter. There she lived out her last years until her death from a lung ailment on 29 May 1857.

A fortnight later, the City Council of Saragossa claimed his remains. In 1870, a procession accompanied the coffin, to which military honours were paid in Cadiz, Seville and Madrid, until its arrival in the Aragonese capital, in the Basilica of El Pilar. In 1909 the remains of Agustina of Aragón, the artillerywoman, were transferred to the church of El Portillo. There she rests, together with other heroines, near the place where she opened fire against the Napoleonic troops. A sculpture by Mariano Benlliure reminds passers-by.

References

- Daniel Aquillué (2021): Guerra y cuchillo. Los Sitios de Zaragoza, 1808-1089. Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros.

- José Luis Cano (2008): Las sitiadas. Zaragoza: Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Agustina Zaragoza entre heroínas”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (138-143). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Diccionario Biográfico Real Academia de la Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/6525/agustina-zaragoza-domenech

- Ana María Freire López (2002): “Historia y literatura de Agustina de Aragón”. Comunicación en el III Coloquio Lectora, heroína, autora (la mujer en la literatura española del siglo XIX)http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/historia-y-literatura-de-agustina-de-aragn-0/html/018bd15e-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_3.html

Teaching activities

The general historical framework. The War of Independence

Read this text:

In 1789, a dynamic was ignited in France that altered the structures of the Ancien Régime, initiating the cycle of bourgeois revolutions that during the 19th century would be associated with the imposition of liberalism. The French Revolution was largely based on the ideas of the Enlightenment, with the predominance of reason, science and technical knowledge. In Spain, these Enlightenment ideas had inspired reformist policies on the part of the absolute monarchy, designed precisely to prevent revolutionary outbreaks such as the one that eventually occurred in France.

The French Revolution therefore provoked a defensive reaction from monarchies such as Spain’s, which gradually abandoned these Enlightenment policies. In France, meanwhile, events were accelerating: resistance and civil war, changes in the system of government, internal conflicts, the decapitation of the kings, different leaderships and betrayals… accompanied these convulsive times, which, however, also saw the development of ideas that heralded a new framework: the loss of privileges of the ruling classes, the extension of rights to other social classes, rational administration, the modernising ideas of the Enlightenment… Many French thought that these advances were universal, that they could only be developed on a global scale: therefore, in order to survive, the Revolution needed to spread to other countries.

Thus, France set in motion a powerful war machine that pitted it against many countries in Europe (for example, it fought the so-called Convention War with Spain). One of its generals, Napoleon Bonaparte, took advantage of the prestige he had gained in military campaigns and, with great political skill, took control of the state, eventually proclaiming himself emperor. The Empire recovered forms of monarchy and apparently betrayed the revolutionary spirit, but it contributed effectively to the spread of those principles associated with progress and consecrated to liberty and equality. The problem was that imposing these principles by force of arms was not exactly the best way.

In the early years of the 19th century, Spain was in a situation of economic, social and political crisis. Napoleon took advantage of the weakness of the institutions and the internal division among the powerful classes (and even the royal family itself) to turn what was a pass to allow his troops to go and conquer Portugal into a full-fledged invasion. In many places, Juntas were set up to organise the defence, the people rebelled, there were all kinds of responses…

Without going into too much detail, these paragraphs provide background information and explain what it was that led the French troops to stand in front of the walls of Saragossa. In what other cities or places was there resistance to the presence of French troops? Was there any kind of centralised organisation?

Many enlightened and liberal-minded people shared the principles of the French Revolution and the civil rights and liberties that these principles claimed to defend… but the brutality and arbitrariness of the Napoleonic troops could not leave them indifferent and there were many who, in spite of everything, stood up to the invaders. People of very different ideas and conditions took part in this resistance. All of them “patriots” as defenders of their country and their landscape, with a much richer concept of “homeland” than is sometimes given to understand: the idea of “patriot” as defender of the monarchy, religion, traditions and order understood in the absolutist way, against the evil represented by the enemy… was unfortunately the idea that prevailed with the return of Ferdinand VII after the withdrawal of Napoleon’s troops. The repression of this absolutist king affected many liberals who had fought against the French and who were now accused of being “Frenchified”.

Look up information about the Constitution of 1812 – in which city was it adopted, how would you define it: democratic, liberal or absolutist, for how many years was it in force, and did it influence any other constitutions? Choose a point that stands out for you.

It is true that there were many “Francophiles” in places (especially cities) and at times when the French imposed themselves and installed their administration. From those who did business with this foreign presence to those who sincerely believed in those revolutionary principles of progress and modernity, to those who accepted the fait accompli with resignation as a means of survival. It was not easy to coexist with all this. Our genius Francisco de Goya, who had liberal ideas, did not take a dim view of French intervention in Spanish politics… until he became aware of the barbarities that had occurred, which he so heartbreakingly captured in his series of engravings “The Disasters of War”. Later, after the arrival of Ferdinand VII, he painted his famous pictures of the 2nd and 3rd of May as “atonement”. Frenchified? liberal? patriot in his own way and on his own patch? simply human? what do you think?

In cities like Saragossa that capitulated in February 1809, the exhausted, sick and starving population had no choice but to accept the triumphant order, the French domination, which would last a few more years. But before that, it had resisted relentlessly.

The local historical framework. The Sieges of Saragossa

If you live in Saragossa, we propose an activity: Identify these places on a map of the city, find out how they are related to the Sites, and design the itinerary of a walk for a Sunday morning, a spring afternoon… or any other time.

- Portillo Square

- Gate of El Carmen

- Sitios Square

- New Tower (San Felipe Square)

- Stone Bridge

1: Monument and church where several heroines are buried; 2: witness of important military actions, it is an important place of memory; 3: monument to the Sieges; 4: (no longer exists) it was the place from where the actions of the besiegers were monitored and the population was alerted; 5: cross in memory of Boggiero, Sas and Warsage.

There are even more sites, maybe you can try to extend the tour….

If you don’t live in Saragossa, you can look for information about aspects of the War of Independence (what happened, if there was any conflict, etc.) in your town, in your region, in a nearby place…

In the midst of the turmoil in Saragossa, on 24 May, the Captain General of Aragon, Guillelmi, was captured, accused of appeasing the French who were approaching the city. A group of farmers from the Arrabal and San Pablo, led by Tío Jorge and Mariano Cerezo, asked General José de Palafox to take charge of the situation. Faced with a power vacuum, with the central institutions collapsed, he convened the Cortes of Aragon (which had not met for over a hundred years) and gave military command of the main Aragonese towns to people he trusted. In mid-June, General Lefebvre’s troops from Pamplona overcame resistance in Tudela, Mallén and Alagón and reached the gates of Saragossa.

Here we find Agustina Zaragoza in action. Her and many more people, of course. Look in the recommended resource (at the beginning of these proposals) for the tool “The heroes of the Sieges”, read these biographies and select the character who has most interested you (apart from Agustina, whose biography there, by the way, contains some errors). Reason your choice.

If you have consulted the resource we recommend, you will be able to link each “heroine” of the Sites with a characteristic of the other column:

- María Agustín a- Turned her palace into a hospital

- Casta Álvarez b- She stood out in the defence of the convent of San José

- María de la Consolación Azlor c- Managed the hospital of Nuestra Señora de Gracia

- María Rafols d- She belonged to the parish of San Pablo

- Manuela Sancho e- She fought in the Puerta de Sancho area

Solutions: 1-d, 2-e, 3-a, 4-c, 5-b

In José Luis Cano’s book Las sitiadas, which we cite among the references, he mentions other women who played an important role in the events of 1808 and 1809 in Saragossa: Josefa Amar (whom we already know from other sources), María Blánquez, Josefa Buil, Juliana Larena, María Lostal, Benita Portolés and María Manuela Pignatelli (Duchess of Villahermosa), who, among many others (Catalina de Mondragón, Josefa Vicente, etc.), deserve to be remembered and recognised.

Places of memory, historical recreation, street names… the Sieges of Saragossa evoke many things and are projected into our present.

Women on the warpath

Let’s go back to earlier times. Look for information about these three women: Boudica, Juana de Arco y María Pita. To which historical moment does each one belong? In which places did they act and are they mythologised today?

Studies and research on social and gender aspects of the War of Independence (and other historical moments) have evolved a lot. They do not focus exclusively on military actions, but extend to broader analyses of women’s own role in society, as the main and determining actress.

It will help you to better understand Agustina of Aragón’s own life story by putting it in a much wider context.

The truth is that little is usually known about Agustina of Aragón beyond her exploits during the first siege of Saragossa in 1808. In the biography you have seen that she did many more things, but they have not been given too much importance, and besides… very strange and contradictory news continue to circulate about the life of this woman.

Agustina strangely

Everything that surrounds Agustina of Aragón mixes reality and fiction, the flesh and blood person and the myth, the woman and the symbol. Here we have pointed out a life itinerary which today appears to be quite clear, but there have been “alternative” accounts which are misleading and which, in many cases, are mixed up with each other and with the real facts, so that we find ourselves in a mess which is difficult to untangle.

Some accounts say, for example, that he was born in Reus (a city not too far from his parents’ village), and sometimes there is talk of a first son who died at a very young age, before Agustina moved to the Aragonese capital. But the unhappy Juan lived with his mother in the besieged Saragossa to die, as we have said, during the painful march of mother and son as prisoners of the French. Agustina would later give birth to another child, also named Juan in memory of her deceased brother, and her husband, Roca, would die as a lieutenant in 1823.

In some places it is said that her first husband died at the beginning of the war in Barcelona and that she arrived in Saragossa remarried or following a captain, a certain Luis de Talarbe who, mind you, never existed! It has even been maintained that the artilleryman whom Agustina replaces in the Portillo action is her beloved. Contributing to the misunderstanding are anecdotes such as the one that apparently occurred shortly after the events of Saragossa, when Agustina spent a few months in Andalusia and another woman pretended to be her, confusing the others with less than exemplary actions.

Agustina Zaragoza has also been involved in the occasional soap opera. It has even been said that, after settling with Talarbe in Valencia, she found out that the first husband she had given up for dead, Juan Roca, was alive and demanded her to return to him. Agustina was salomonic and decided to distance herself from both of them. When the news reached her that the first husband had really died, she tried to return to Talarbe, but he, who had gone to America, married there. She then retired to Ceuta, married to a doctor, Cobos, who was much younger than she was.

Part of this confusion can be explained by Agustina’s own family. Her daughter, Carlota Cobos, published a novel in 1859, La ilustre heroína de Zaragoza (The Illustrious Heroine of Saragossa), in which she mixed fiction and reality around her mother, who had died shortly before. Talarbe appears there, who (according to research by Ana María Freire) could correspond to the military man José Carratalá, whose service record indicates that he coincided with Agustina in the second siege of Saragossa and in other later posts, from her capture and escape to France, to military actions in Tortosa and Vitoria. For whatever reason, Agustina (who in her later years was aware of the writing of the novel) was pleased that her daughter made this wink and invented an “alternative”, novel-like life.

We already know that the viral phenomenon also affects the propagation of falsehoods… and this partly explains why erroneous information about the life of Agustina of Aragón continues to run rampant.

Agustina, romantic character split in two

A double memory has been spread of our heroine:

The heroine of the Sieges, used for propaganda, for the epic of Spain against the invader, as a defender of the tradition that the enemies want to destroy.

The contradictory, inconstant woman, given to sentimental dalliances?

The first Agustina has starred in novels, plays, operettas, films…

Find information about the film Agustina de Aragón (1950, directed by Juan de Orduña, starring Aurora Bautista).

What strikes you about Agustina’s image? It is an element of debate, because the boundaries between a sexualised and dominant woman (“survivor in a man’s world”), subject and object… are not so clear, and there is room for very different opinions.

Fiction is fine: it entertains us, it enriches our experiences, and we can appreciate it in context. The problem is when fantasies are given the status of truth, when fiction intervenes in such a way that it contaminates reality. When the heroic idea is too worn out, there are those who confuse “humanising” with other things. And then, for example, the second Augustina can come into play.

The heroine is exalted and glorified. But the woman, prey to sensationalism, is sold as promiscuous. The writer Ángeles de Irisarri has spoken of a white and a black legend about Agustina: “she had not yet come down from the bastion of El Portillo and already people were saying things [such as] that she was pregnant (…). It was also said that she was in a carriage with a bunch of prostitutes, like a madam…”.

The newspaper ABC opens a content of 29 May 2017 with this headline: “La azarosa poligamia de Agustina de Aragón” (Agustina of Aragón’s hazardous polygamy). The news item continues: “Heroine in the Saragossa resistance against Napoleon’s troops, she was married to two men at the same time, left both and married a third, all of them military men”.

Apart from the fact that this is a lie, and beyond the importance of her affective and sexual life for every human being… there are other things that should draw our attention to Agustina of Aragon. Can you think of what these things might be?

For example, she did a lot more than light a fuse, she was a professional who earned her living in a profession linked to the military world. She raised a family, she overcame adversity…

Agustina Zaragoza, a Catalan woman eternally linked to Aragon and a cosmopolitan woman who lived and made many places her own… is an image, an impulse, a tenacity. Hundreds, thousands of women could line up under her effigy, women who in extreme situations, in situations of threat and aggression, rise up and stand up. But also those who suffer in silence from mistreatment or neglect.

To close… a piece of advice from Agustina

Courage, daring, heroism… are basically very fickle concepts that are very easy to inflame or shrink. Perhaps we should speak of courageous attitudes rather than courageous people. Perhaps the hero, the heroine, is within oneself, within oneself.

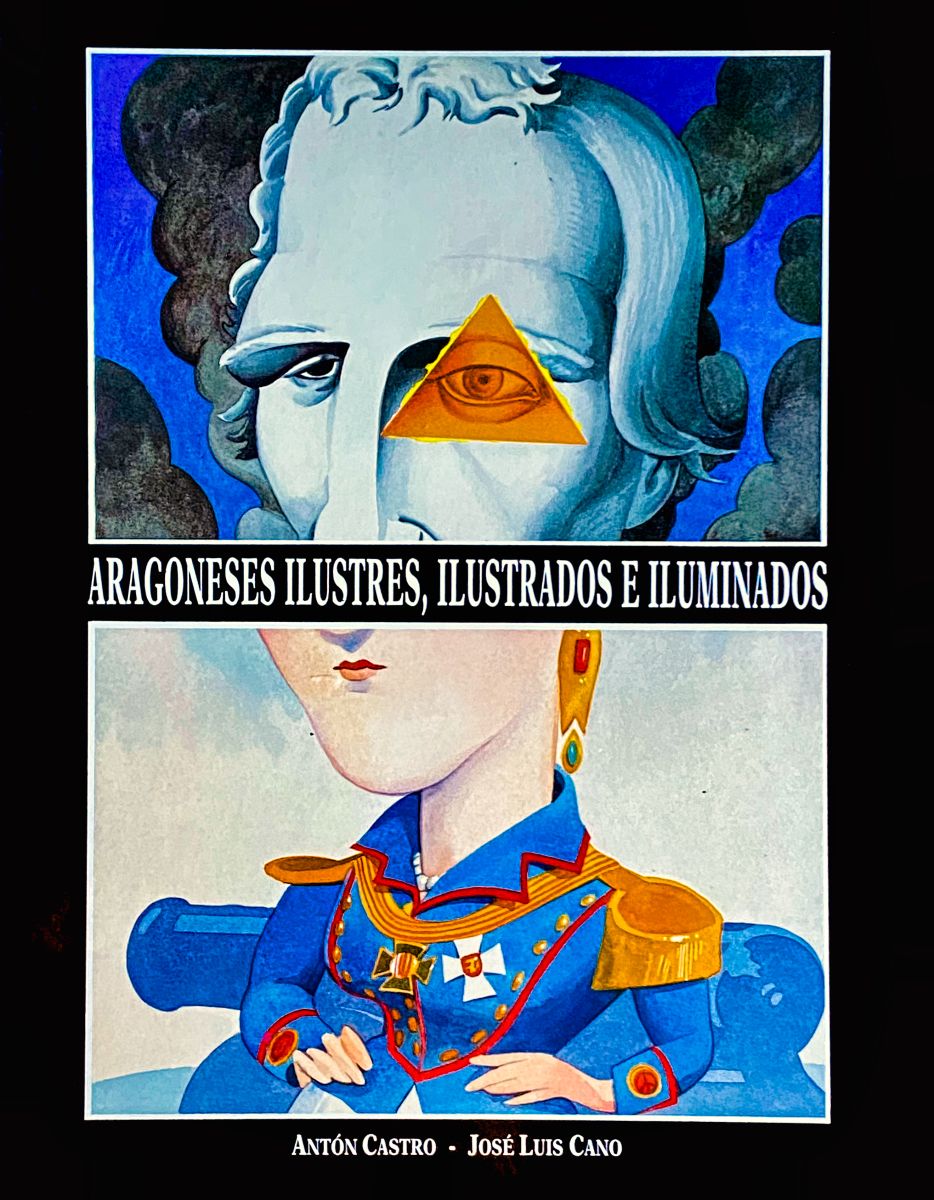

Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: