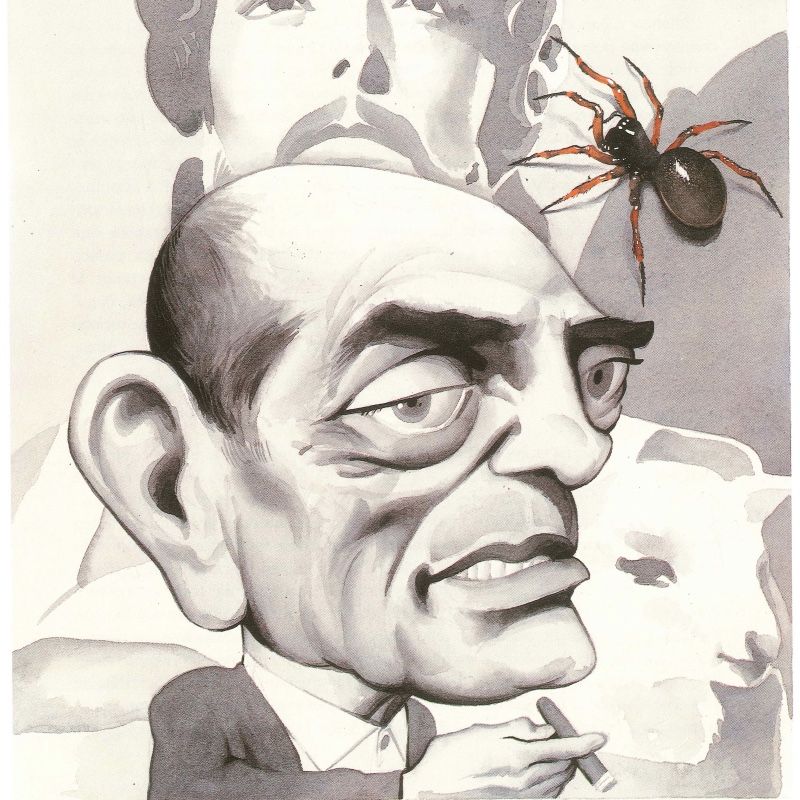

Luis Buñuel

Cinema as dream, emotion and instinct

Calanda, 1900 – Mexico City, 1983

Leonardo Buñuel was a merchant who had become rich in Cuba and returned to his native Calanda when the island went on the warpath against Spain. He married a young woman from the town, María Portolés, and acquired property whose good income allowed him to move to live in Saragossa with his family. By then, Luis was three years old.

The eldest of the seven Buñuel siblings, he studied at the Jesuit school with good marks but without hiding an insolence that came from within him. For Santa and holidays, he returned to Calanda, where he made little theatres with cardboard figures and shadow puppets and played at celebrating mass. Fables and unbridled imagination went well with someone who had been a spectator of comedies and dramas at the Principal theatre since he was a child, visited the film establishments of Coyne and Farrusini and was a voracious reader of adventure and detective novels.

Life

At the age of fourteen he was expelled from the Jesuits and enrolled at the Instituto de Enseñanza Media (the future Goya Institute). At seventeen he went to Madrid to study to become an agricultural engineer, although he soon became interested in Natural Sciences (and more specifically entomology) and ended up enrolling in Philosophy and Arts to study for a degree in History, which he would complete in 1924. By then he had a girlfriend from Madrid, whom he had met during a summer stay with her family in San Sebastian. Concha Méndez was one of the “sinsombrero”: the group of women writers and intellectuals linked to the Generation of 1927.

This cultural environment was very present in the Residencia de Estudiantes: a project of the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios, heir to the pedagogical models of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Buñuel would live there for years, and his stay there would have a profound effect on him: he met Federico García Lorca, Salvador Dalí, Pepín Bello, Rafael Alberti, Juan Ramón Jiménez… During those years he attended gatherings (such as the one at the Pombo café held by Ramón Gómez de la Serna), wrote poems and short stories, took an interest in naturism and boxing, and continued to be a bully with a clear sense of friendship. Much later he was to recognise his absolute debt to Federico: “Without him, I would not have known what poetry was”.

Work

A trip to Paris in 1925 opened him up to the avant-garde, he consumed cinema without rest, dabbled in theatre and became assistant director to the director Jean Epstein. In those years he moved between France and Spain: he published film reviews, played small roles, ran a film club at the Residencia de Estudiantes… In 1929 he obtained money from his mother to finance the filming of a screenplay written jointly with Salvador Dalí in which they gave free rein to the possibilities of the unconscious, delirium and provocation. The success and controversy of An Andalusian Dog in Paris introduced him fully into the world of surrealism: Max Ernst, Paul Éluard, André Breton, Louis Aragon, Tristan Tzara, Réné Magritte… The following year, The Golden Age insisted on aesthetic principles that challenged bourgeois and conventional morality. The result: boycott of screenings by extreme right-wing groups and banning by the authorities. The Golden Age was not distributed in France until 1980.

Hollywood

In 1930 he met Charles Chaplin and Sergei Eisenstein in Hollywood and was hired by Paramount. Three years later, with money from his friend Ramón Acín, he filmed Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan, a film that was censored and banned for its crude social denunciation. Married to Jeanne Rucar (with whom he would have two children: Jean-Louis and Rafael) and settled in Spain as a dubbing director and producer at Filmófono, the outbreak of the Civil War surprised him in Madrid and he put himself at the service of the Republican government, coordinating documentaries and propaganda actions and supervising the Spanish pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris.

After the defeat of the Republic, he worked in the United States as a producer and supervisor, working for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and later for Warner in Los Angeles… by then he had broken off his relationship with Dalí, who was ideologically diametrically opposed to him. A man of the left, his situation in the United States became increasingly uncomfortable and he got a job in Mexico to direct Gran Casino: a failure despite having stars such as Jorge Negrete and Libertad Lamarque. He recovered with El gran calavera, whose success allowed him to undertake more personal projects such as Los olvidados, a stark portrait of poverty in the big city with which he triumphed at the Cannes Film Festival. In the 1950s he consolidated his career with titles such as Susana, Él, La ilusión viaja en tranvía, El río y la muerte and Ensayo de un crimen, among others, in which melodrama, surrealist touches, a very personal vision of loneliness, picaresque and black humour are outlined.

With Nazarín (very well received at the Cannes Festival), El ángel exterminador and Simón del desierto (1964), he completed his Mexican period. Before that, in 1960, he had travelled to Spain to shoot Viridiana, a Spanish-Mexican co-production for which he had co-written the script with Julio Alejandro. The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, but the most conservative church considered it an insult to religion, and the Franco regime banned it in Spain (it was not screened until 1977).

In 1963, he entered the French film industry (with whom he had already worked on previous films) with Diary of a Chambermaid, Belle de jour (Golden Lion at Venice and a great success with the public), The Milky Way, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1972) and The Phantom of Liberty. In these films, in which the screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière played a very important role, he further exploited the surrealist vein, playing with chance and the contradictions of human beings. He had previously filmed Tristana in Spain and would do so again with That Obscure Object of Desire, his last film in 1977.

His last years were full of tributes and reunions. In the 1960s he returned to Saragossa and his native Calanda. In 1972 the great filmmaker George Cukor offered him a tribute dinner at his home in Los Angeles, attended by true legends of universal cinema such as Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Milder, William Wyler, Robert Mulligan, Robert Wise, George Stevens and Rouben Mamoulian. He was also the subject of a major tribute at the George Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1982. By then he had already undergone prostate and gall bladder operations, and cancer was eating away at him. He breathed his last in Mexico City in July 1983. His ashes were scattered in 1997 on Mount Tolocha, near Calanda, where he returned never to leave again.

References

- There is an immense bibliography and written work on Buñuel. His memoirs, Mi último suspiro (written with Carrière), 1982, have been reprinted many times.

- José Luis Cano (1999): Buñuel y don Luis. Zaragoza, Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Buñueliana de caprichos”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (210-217). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Agustín Sánchez Vidal (2004): Luis Buñuel. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/voz.asp?voz_id=2653

- Diccionario Biográfico Español, Real Academia de Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/9265/luis-bunuel-portoles

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Bu%C3%B1uel

- In 2000, the Aragonese singer-songwriter Ángel Petisme dedicated a book-disc to him, Buñuel del desierto (LCD Prames), available on platforms such as Spotify. This work was part of the activities for the centenary of the filmmaker’s birth, of which there is still interesting information available today:

- Website of the Government of Aragon:

https://web.archive.org/web/20070118042616/http://bunuel.aragob.es/ - Centro Virtual Cervantes Exhibition (It is dangerous to look inside. Buñuel, 100 years): https://cvc.cervantes.es/actcult/bunuel/indice.htm

- Exhibition Luis Buñuel.. El ojo de la libertad. (Residencia de Estudiantes): http://www.residencia.csic.es/expo/bunuel/ficha.htm

Teaching activities

A recommendation to start with

Buñuel’s cinema

Buñuel has a very extensive filmography. We have already talked about some of his works, those considered the most important, in the biography. Without counting others in which he acted, was a producer or screenwriter… the films he directed were the following:

- Un perro andaluz (Un chien andalou, 1929).

- La edad de oro (L’âge d’or, 1930).

- Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan (Las Hurdes, 1933).

- Gran Casino (En el viejo Tampico, 1947).

- El gran Calavera (1949).

- Los olvidados (1950).

- Susana (Demonio y carne, 1951).

- La hija del engaño (1951).

- Una mujer sin amor (Cuando los hijos nos juzgan, 1952).

- Subida al cielo (1952).

- El bruto (1953).

- Él (1953).

- La ilusión viaja en tranvía (1954).

- Abismos de pasión (1954).

- Robinson Crusoe (realizada en 1952 y registrada en 1954).

- Ensayo de un crimen (La vida criminal de Archibaldo de la Cruz, 1955).

- El río y la muerte (1954-1955).

- Así es la aurora (Cela s’appelle l’aurore, 1956).

- La muerte en el jardín (La muerte en este jardín, La mort en ce jardin, 1956).

- Nazarín (1958-1959).

- Los ambiciosos (La fiebre sube a El Pao, La fièvre monte a El Pao, 1959).

- La joven (The Young One, 1960).

- Viridiana (1961).

- El ángel exterminador (1962).

- Diario de una camarera (Le journal d’une femme de chambre, 1964).

- Simón del desierto (1964-1965).

- Belle de jour (Bella de día, 1966-1967).

- La Vía Láctea (La Voie Lactée, 1969).

- Tristana (1970).

- El discreto encanto de la burguesía (Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie, 1972).

- El fantasma de la libertad (Le fantôme de la liberté, 1974).

- Ese oscuro objeto del deseo (Cet obscur objet du désir, 1977).

Of course, this selection is very subjective and responds to the personal criteria of the author of the article. But through this one you can get an idea of the characteristics of Buñuel’s cinema. Read the comments and say which film corresponds to each of these traits:

- It was banned in Spain until after Franco’s death.

- French production, won an Oscar from Hollywood

- A group of rich people can’t leave a room.

- Part of Unesco’s “Memory of the World” programme

- A bourgeois woman, bored with convention, leads a double life.

- She was able to film it because a friend won the lottery.

Solutions: 1. Viridiana / 2. El discreto encanto de la burguesía / 3. El ángel exterminador / 4. Los olvidados / 5. Belle de jour / 6. Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan

Which one catches your attention the most, and are you curious about any of these films? Discuss it in class: perhaps you could screen one of them, and then exchange impressions, opinions and reflections on what you have seen.

Of all these films, the most groundbreaking and shortest was Un perro andaluz. It can be seen on the internet under public domain, and we propose a specific activity about it.

Provocation as art. From surrealism…

This piece was born from the confluence of two dreams (Dalí dreamt that ants swarmed through his hands and Buñuel dreamt of a knife that cut the moon in two). In barely twenty minutes, it skips all conventional narrative schemes. It uses non-linear time (with jumps forwards and backwards); through the aggressiveness of the images and the disturbing, it seeks to provoke a moral impact on the spectator, constantly referring to delirium and dreams. Instincts, carnal desire, memories of the past, religious upbringing, oppression, punishment, authority and criticism of a society that is considered rotten (such as those carnuces in drag) also parade through the film. A sense of humour (a black, somber and sardonic humour), death always on the horizon, insects, weapons (which he was passionate about but never used), eroticism? In a more or less explicit way, to a greater or lesser extent, his filmography covers all these subjects.

In this paragraph we have used two Aragonese words: “carnuces/carnuz” and “somarda”. What do they mean, and are they both included in the Diccionario de la Lengua Española?

We agree that it is a difficult film to define and understand. Cinema, like art in general, is also there to make us think, but also to shake us up a bit, to make us uncomfortable.

Do you think this kind of cinema is easy to watch? What kind of films or series do you like to watch? Do you prefer fiction that tells you pleasant things or fiction that forces you to ask yourself questions and question things? After watching Un perro andaluz… Which image struck you the most? Do you think it seems to be an accumulation of dreams and nightmares? Which representatives of authority appear in the film? Why do you think this film caused so much controversy?

Look for information about surrealism, where and when it was born and developed (why precisely in those years?).

Surrealism was born in Paris in the 1920s, although it expanded in different directions. It was inspired by psychoanalysis and the exploration of the subconscious, leaving aside the rational. As a literary and artistic avant-garde, it sought to question traditional values, to upset their balance… in this sense it obeyed the consideration of art as something revolutionary. The interwar period in Europe, the twenty years between the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and the outbreak of the Second World War (1939), were turbulent times of crisis and excitement. A fertile ground for reaping the fruits of all this defiant creativity in an erupting world.

… to realistic drama. Passion and suffering as art

A tragic story in the wake of Italian neorealism, it belongs to another historical dynamic (that of the post-war world) and offers the less friendly face of a country, Mexico, whose economic growth and cultural development in those years did not reveal pockets of poverty and inequality.

If twenty years earlier, in Un perro andaluz, he had shown violence, tempest and anguished lyricism, now in Los olvidados Buñuel shows solidarity with the weak, whose misery he depicts in stark, unsweetened terms (with a similar expressionism to that which he had captured in Las Hurdes). The writer Octavio Paz defined Los olvidados as “passionate and ferocious art, contained and delirious, cold lava, volcanic ice”.

The readings of young Luis

Luis Buñuel was a great reader from an early age: seduced by adventure and detective novels, he was not averse to essays and more complex works from his father’s extensive library. He also wrote a lot (“A good writer has to be a good reader”): lyrical pieces in the 1920s, surrealist poems with echoes of the greguerías and ultraísmo, film reviews, his own screenplays which are literature in its purest form…. The very narrative of his films contains elements of the picaresque of the Golden Age, of romantic heroes, of the impulses of nature, of realism, of expressionism?

Some of these elements could be guessed from the books that seduced him as a teenager. We have selected five of them (some of which he would adapt for film when he grew up). Relate them to their authors:

- Robinson Crusoe a) Charles Darwin

- El Buscón b) Daniel Defoe

- Tristana c) William H. Ainsworth

- Rookwood (Dick Turpin) d) Francisco de Quevedo

- El origen de las especies e) Benito Pérez Galdós

Solutions: 1-b; 2-d; 3-e; 4-c; 5-a

Calanda in the childhood and maturity of the filmmaker… Calanda in his legacy

Calanda is a town in the Bajo Aragón region of Teruel. It is part of the Drum and Bass Drum Route.

Find the names of the other towns that make up this route.

Albalate, Alcañiz, Alcorisa, Andorra, Calanda, Híjar, La Puebla de Híjar, Samper de Calanda and Urrea de Gaén

The crucial moment of the celebration of Santa Week in this town is the “breaking of the hour” at midday on Good Friday.

Look for images on the internet of the “breaking of the hour” in Calanda. Do you know what it is meant to represent?

It represents the roar that is said to have been heard on Earth after the death of Jesus Christ on the cross.

Buñuel, who had experienced this celebration as a child, always kept the beating of the drums in his memory: he made them sound in some passages of his films (La edad de oro, Nazarín y Simón del desierto) and, when he was already a famous filmmaker and could re-enter Spain, he joined in this celebration (there are images of Buñuel drumming with his son Jean-Louis in 1963).

Calanda (which is also famous for its stupendous designation of origin peaches, and for a miracle attributed to the Virgen del Pilar in the 17th century, when a lame Calandino apparently recovered his leg) is part of the rich personal universe that Buñuel transferred to his films. As Antón Castro says, “once he knew he wanted to make films of eminent visual power about a conflicting subjectivity – sex, religion and destiny – he only had to turn his gaze to the yellowed photographs of his domestic universe: Calanda, the Buñuel family mysteries, peasant life, childhood nourished by prodigies and horrors”.

Nowadays, the Buñuel Calanda Centre is a reference for research and dissemination, for those who understand Buñuel’s work and for those who wish to come into contact with the Aragonese artist and the environment that marked his life and his work. It hosts a permanent exhibition and other temporary exhibitions and organises different activities.

Spanish directors at the Oscars

Luis Buñuel was the first Spanish director to win an Oscar from the Hollywood Academy. As you know, it was for The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (a parable about decadence to the point of absurdity), which won him the award in the category of “Best Foreign Language Film”. The film was a French production. After Buñuel, four other Spanish directors would go on to win the same award in that category.

We give you the names of these directors, and the Oscars in which each of them was awarded. All you have to do is find and complete the table with the title of the corresponding film:

| 1982 | José Luis Garci | |

| 1992 | Fernando Trueba | |

| 1999 | Pedro Almodóvar | |

| 2004 | Alejandro Amenábar |

Solutions. In the same order: Volver a empezar; Belle époque; Todo sobre mi madre; Mar adentro

Other Aragonese filmmakers of the 20th century (and also of the 21st)

Buñuel has gone down in the great universal history of cinema. But there are other Aragonese who have also written glorious pages of the seventh art. Their works have stood the test of time very well.

We recommend that you take a look at the creations of these three great Aragonese filmmakers

José María Forqué (Zaragoza, 1923 – Madrid, 1995). His most famous work, Atraco a las tres, from 1962, projects a very acid criticism of the society of the time and a tender look at human ambitions and frustration: the comic tinge allowed him to avoid censorship (in the face of the ignorant and obtuse, wit and wit always win).

José Luis Borau (Saragossa, 1929 – Madrid, 2012). Also a prestigious screenwriter and director, his best-known film is Furtivos (1975), which won the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Festival. Characters trapped in an atmosphere of claustrophobia which, due to the year in which it was released (1975, the same year as the death of the dictator Franco), has given rise to many interpretations.

Carlos Saura (Huesca, 1932). Although it was not the first of his films, “La caza” (1965) was a boost to his career, and consolidated a very extensive and recognized filmography, which in 2022 is still producing results. This film is seen as a metaphor for the Civil War, and delves into the primal instincts of human beings.

Epilogue

Buñuel was described by his wife, Jeanne, as “jealous and domineering” but at the same time “tender, cheerful and with a sense of humour”. He considered himself “an atheist, thank God”, paradoxical and a man of contrasts.

Antón Castro says that Buñuel’s work is “an admirable and corrosive synthesis of Hispanic tradition, of the lights and shadows of the Golden Age, of the influence of religion and of his commitment to the language of the avant-garde. He creates a gallery of characters whose existence oscillates between violence, sexual repression, a deep obsession with death and the consideration that goodness often leads to failure and disaster”.

His influence on the cinema of the second half of the 20th century and even today is unquestionable. The cinema of other world-famous authors (Hitchcock, Fellini or David Lynch) owes much to the worlds dreamt and explored by Luis Buñuel.

Buñuel and Don Luis

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: