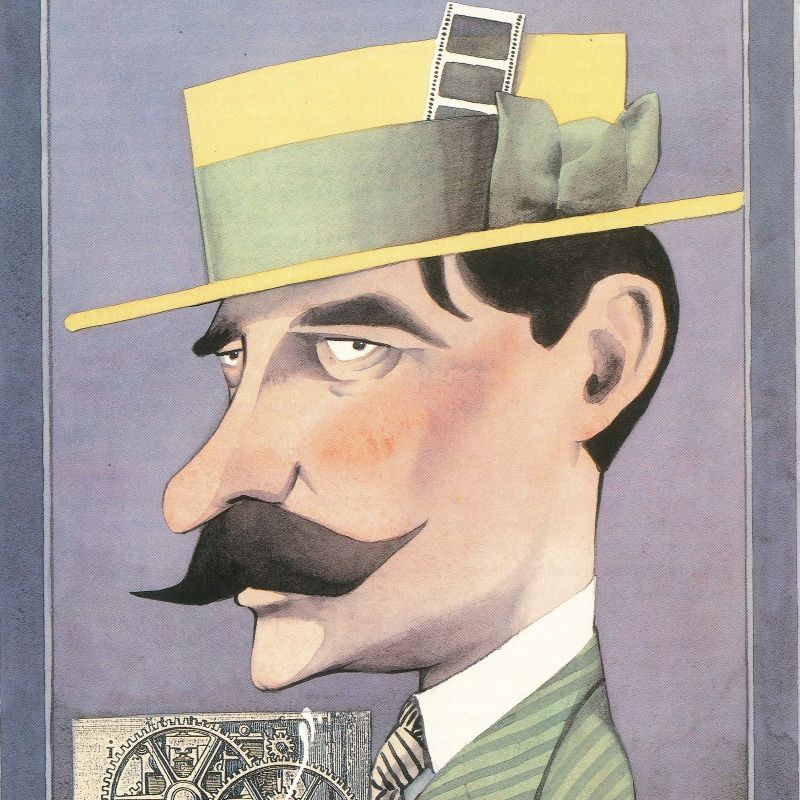

Segundo de Chomón

The magician of cinema

Teruel, 1871 – París, 1929

Who doesn’t like to watch a cinema film, whether in a large cinema, in the company of family or friends and dozens of strangers, or at home, alone, comfortably ensconced on the sofa? Well, that pleasure would not be the same without the brilliant ideas of an exceptional Aragonese, Segundo de Chomón, who in the early years of the industry’s existence introduced innovative special effects and participated in the development of a new language, cinematographic, which had hitherto been non-existent.

Life

Segundo Víctor Aurelio de Chomón y Ruiz was born in October 1871 in Teruel, where his father worked as a doctor. At the time, Teruel was a small town of some ten thousand inhabitants, quite isolated from the major national and international capitals. His childhood and early youth are not very well known. It seems that he wanted to study engineering and perhaps began his studies. The fact is that in 1895 he travelled to Paris and there he met what were to become the two great passions of his life, his wife, Julienne Mathieu, and the cinema, the moving image.

It was precisely at the end of December 1895 that the Lumière brothers projected the first “films” in history in the French capital. They were less than a minute long. One of them showed the arrival of a train at a station, a scene that frightened the spectators, who had never seen anything like it before and ran away believing that the train was going to run them over. The invention attracted attention and soon spread as a fairground spectacle, along with the booths exhibiting exotic animals, the bearded woman or the magician who could tell the future.

Work

Over time, silent and black-and-white films became more refined. They became longer, began to tell short stories and included “visual effects” that amazed audiences. Chomón became interested in film early on, first through his wife, who belonged to a family of actors and who became involved in the hand-colouring of short films, frame by frame (there were 16 frames on each second of tape). Between 1897 and 1899 he had to do his military service in Cuba, where a war of independence was being fought. But on his safe return to Paris, he also took up the task of colouring films. He invented an automatic colouring system, with stencils, and was then hired by a large company, Pathé.

In 1902, Pathé sent him to Barcelona to market his invention.

In the Catalan capital, Chomón shot his first short films, full of tricks. With special cameras, filters, transparent backgrounds, models, shadows, articulated dolls, double exposure, overprints (he used the same tape twice at different distances, so that some actors appeared giant and others small, as in Gulliver or Tom Thumb) or shooting frame by frame, he managed to make things happen on the screen as if by magic.

Special effects

Pathé, the world’s leading film production company at the time, decided to bring him back to Paris. And it put huge studios and big budgets at his disposal. For a few years, Chomón produced acclaimed special effects for fantasy and entertainment films. In the film Elusive Jim, for example, when the protagonist is chased by the police, he turns himself into a thin piece of paper to get out of a closed boot; then he escapes from a sack thrown into the water; he flees on a bicycle that he kept folded up like a cardboard box and rides it onto a moving train; While trying to stop him, one of the policemen is run over and broken in two, but a worker who is putting up posters and sees him hits him with paste and manages to revive him; Jim leaves two pursuers flattened with a slam of the door; they catch him and put a big box on him, but in the end he slips through a hole and turns into a kind of sausage.

In 1910, Chomón returned to Barcelona. The cinema was no longer a fairground show. Films were seen in theatres, lasted longer, had a script and told complex stories. In Spain he filmed films of many different genres: comedies, dramas, zarzuelas, historicals, documentaries… And for some he also wrote the screenplay. In many of them he introduced narrative novelties and original tricks.

Only two years later, in 1912, he was hired, with an astronomical salary, by Itala Films, the Italian film company that had replaced Pathé as the most important in the world. In Turin he was involved, among others, in the shooting of Cabiria, a feature film directed by Giovanni Pastrone, which tells the story of the struggle between the Romans and the Carthaginians. He used his imagination to create spectacular scenery, erupting volcanoes, mass battles, fires, the battle of war fleets, disturbing dreams… He made the sequences dramatic through the lighting and made the camera move, not the actors. In the editing, moreover, general shots and close-ups were interspersed. Cinema was no longer a “filmed theatre”. It now had a vocabulary of its own.

The First World War devastated the European film industry. From then on it was the United States where it developed and triumphed. After the conflict, Chomón settled in Paris. There he experimented with colour film. But he still had time to take part in another great film, Napoleon, by the French director Abel Gance, a super-production of more than six hours, eventually reduced to three, about the French Revolution. And also in a Spanish film with the actress Concha Piquer, El negro que tenía el alma blanca, famous for a dream sequence featuring a gorilla. In 1929, he returned ill from a trip to Morocco, where he had gone to rehearse his coloured film. He died shortly afterwards. His name, little known to the general public, soon fell into oblivion. Despite this, today he is recognised worldwide as one of the most brilliant film pioneers. Those who succeeded in making motion pictures as we know them today.

References

- José Luis Cano (2001): El mago Chomón. Zaragoza: Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Segundo de Chomón, la alquimia del pionero”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (168-173). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Carlos Fernández Cuenca (1972): Segundo de Chomón, maestro de la fantasía y de la técnica. Madrid: Editora Nacional.

- Juan Gabriel Tharrats (1988): Los 500 films de Segundo de Chomón. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias.

- Agustín Sánchez Vidal (1992): El cine de Chomón. Zaragoza: CAI.

- Spanish Biographical Dictionary, Royal Academy of History: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/14147/segundo-de-chomon-ruiz

Teaching activities

The birth of cinema

Lumière brothers, August (1862-1954) and Louis (1964-1948), inventors of the cinematograph, which served both as a camera and a film projector.

Gerorges Méliès (1861-1938), fantastic cinema. He founded the first film studio to use mechanical systems to hide areas from the sun, trap doors and other mise-en-scène mechanisms. In 1902 he created what is considered his greatest work, Journey to the Moon.

Charles Pathé (1863-1957), founder of the Pathé Fréres (Pathé brothers) company, which, during the early years of the 20th century, was the largest film production company in the world.

Giovanni Pastrone (1883-1959), director and producer, pioneer of moving pictures in Italy. In 1907 he became managing director of Itala Films. He introduced a filming system, the tracking shot, which became a key element in the industry. His filmography includes his film Cabiria (1914), in which Segundo de Chomón participated.

These are names that are mentioned in the text and which, together with Segundo de Chomón (less known but no less important), are associated with the birth and early years of cinema.

Find out more about the cinema of the time and write a brief account of the birth of cinema and the primacy of Europe during the early years of the film industry.

The first film to be shot and shown to the public in Paris was Exit of the Lumière factory workers (1895), which was less than a minute long.

Another early film, The Arrival of the Train at Ciotat Station (1895), caused a great sensation in the auditorium where it was shown. Both were shown at the Salon Indien du Grand Café à Paris on 28 December 1895. Cinema was born.

Watch these videos and comment on what you think of them and the major differences you observe with respect to today’s cinema.

Segundo de Chomón, father of special effects

He was a specialist in trick and development, lighting and photography technician, director, pioneer of fantastic and animated films. Chomón carried out all these tasks throughout his career.

The text mentions some of the techniques that were used at the dawn of cinema to achieve effects and greater spectacularity, many of which were devised or perfected by Chomón, such as travelling, the overhead shot, overprinting, inverted movement, crank movement, transparencies…

Make a glossary of these terms and look for examples on the internet to understand them better:

Director

Lighting technician

Photographic technician

Trick and development specialist (in special effects)

Fade to black

Crank step

Transparencies

Travelling

The search for colour

On the left, Julienne Alexandre Mathieu, Chomón’s wife, shown in the photo above.

One of the obsessions of the first producers, Pathè and Méliès, was the quest to reproduce colour on film. As in photography, this was initially only achieved by manual colouring. It was in this field that Chomón’s first works in cinema began.

On his return from the war in Cuba, Chomón settled in Paris where his wife Julienne Alexandre Mathieu, a theatre and vaudeville actress, had acted in some films and worked in the workshop for hand-colouring films, frame by frame, founded by Georges Méliès. The man from Teruel joined this laborious task. At that time, a film had 16 frames per second.

Chomón soon devised a procedure for faster colouring, based on stencils. Pathé later perfected this system and registered it under the name “Pathécolor”. The French production company only hired girls with perfect eyesight and drawing skills for this work.

The film The Tulips, directed by Segundo de Chomón in 1907 for Pathé and which you can see in the following link, has a duration of 3 minutes and 20 seconds. If films at that time had 16 frames per second, how many frames had to be coloured? A lot of work, isn’t it?

In the last years of his life, Chomón collaborated with Ernesto Zollinger to develop a colour film system. Basically, it consisted of a device with two velvet-covered wheels impregnated with red and green that alternately inked the film so that one frame was in red and the next in green. It used very clear filters that allowed shots to be taken in any lighting and were suitable for any type of projector without the need for accessories.

Colour in film as we know it today, not coloured but recorded at the same time as the film is shot, was not achieved until the 1930s, in the already dominant Hollywood film industry.

France, Italy, Spain…

Segundo de Chomón accompanied the early years of cinema like no other professional, having worked in the main studios and with the most outstanding producers and directors of the time.

Research and comment on which companies he worked for, in which countries and to what extent his work was valued at the time.

Also look up some of the films in which he was involved as a technician.

Highlight some of his films as a director.

Do you think that this outstanding figure of Spanish cinema is sufficiently well known today? Give your reasons for your answer.

Perhaps his most popular film is Hotel Eléctrico, which he directed in 1908 and which you can see at the following link. It is considered a masterpiece of early cinema. It was shot on one hundred and forty metres of Pathé virgin celluloid film. In it Chomón offers his best version of the “crank step” and shows all his talent in the use of a whole portfolio of special effects.

For you to do it

Before the cinematograph was invented, there were numerous devices that somehow achieved the longed-for reproduction of the moving image. Among these devices were:

The thaumatrope, the first device, invented in Great Britain in 1825, which made it possible to give motion to static images.

The phenakistoscope, invented in Belgium by the physicist Joseph Plateau in 1832, which was the first device to animate a sequence of static drawings broken down into different phases of movement.

The zootrope, invented in Great Britain in 1834, which made it possible to animate several phases of a cyclical movement.

The folioscope, patented in Great Britain in 1868, is a book that generates a sensation of movement in the images it contains by turning its pages.

Look for images to see how it works.

In these links you will find instructions on how to make a phenakistoscope and examples to inspire you. See how it turns out.

The magician Chomón

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: