Santiago Ramón y Cajal

The culture of effort, the value of willpower

Petilla de Aragón, 1852 – Madrid, 1934

Ramón y Cajal spent his early years in Larrés (his family village), Luna, Valpalmas and Ayerbe, where his father, Justo Ramón, completed his string of postings as a rural doctor. Santiago was a restless, mischievous child with an innate curiosity. His father, stern and not very fond of jokes, did not allow him to develop his great love of drawing (which he would later apply very well to his research), but he instilled in Santiago a culture of effort that he himself (who had progressed from barber to second-rate surgeon, until he obtained the post of professor of dissection at the University of Saragossa) had followed to the letter.

After attending the Escolapios in Jaca, he finished his baccalaureate studies at the Institute of Huesca. In the holidays, his father tried to keep him on a short leash, to dominate his untamed tendencies and to instil in him knowledge of anatomy with skeletons from the Ayerbe cemetery. Passionate about physical education, fantastic literature and philosophy, he went to Saragossa to study medicine. He never lost his rebelliousness, but he was disciplined, studied, allowed himself to be guided by his father, and obtained his degree in 1873.

Life

Our protagonist took up a post in the Military Health Service, witnessed episodes of the Carlist War in Catalonia and was posted to Cuba. On that island he was horrified by the corruption of the commanders and the helplessness of the troops, and contracted malaria. He returned weak and ill to Saragossa, and became an intern at the Hospital de Nuestra Señora de Gracia and assistant lecturer in anatomy at the University of Saragossa.

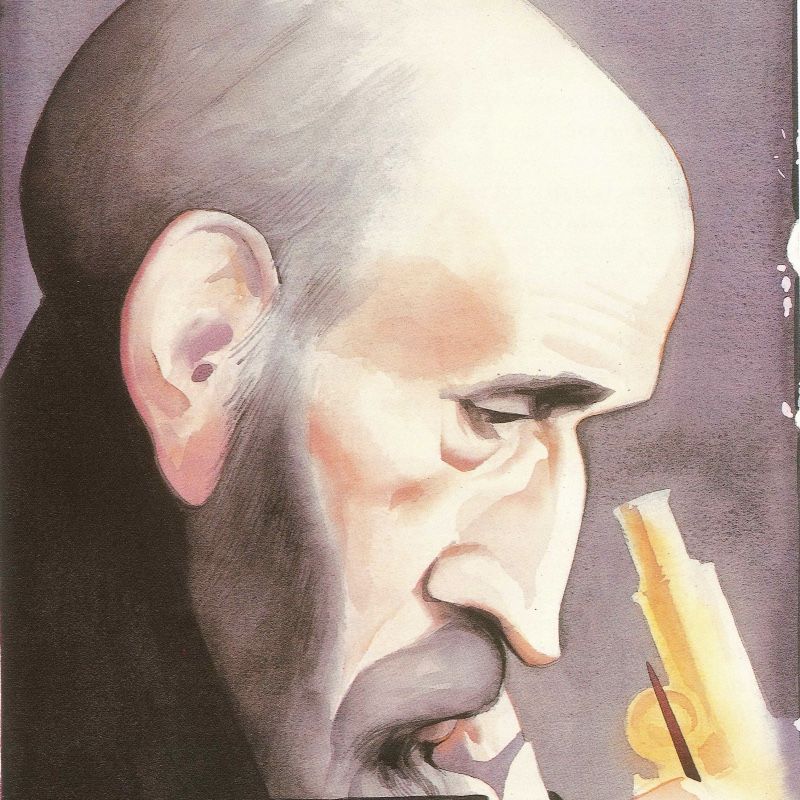

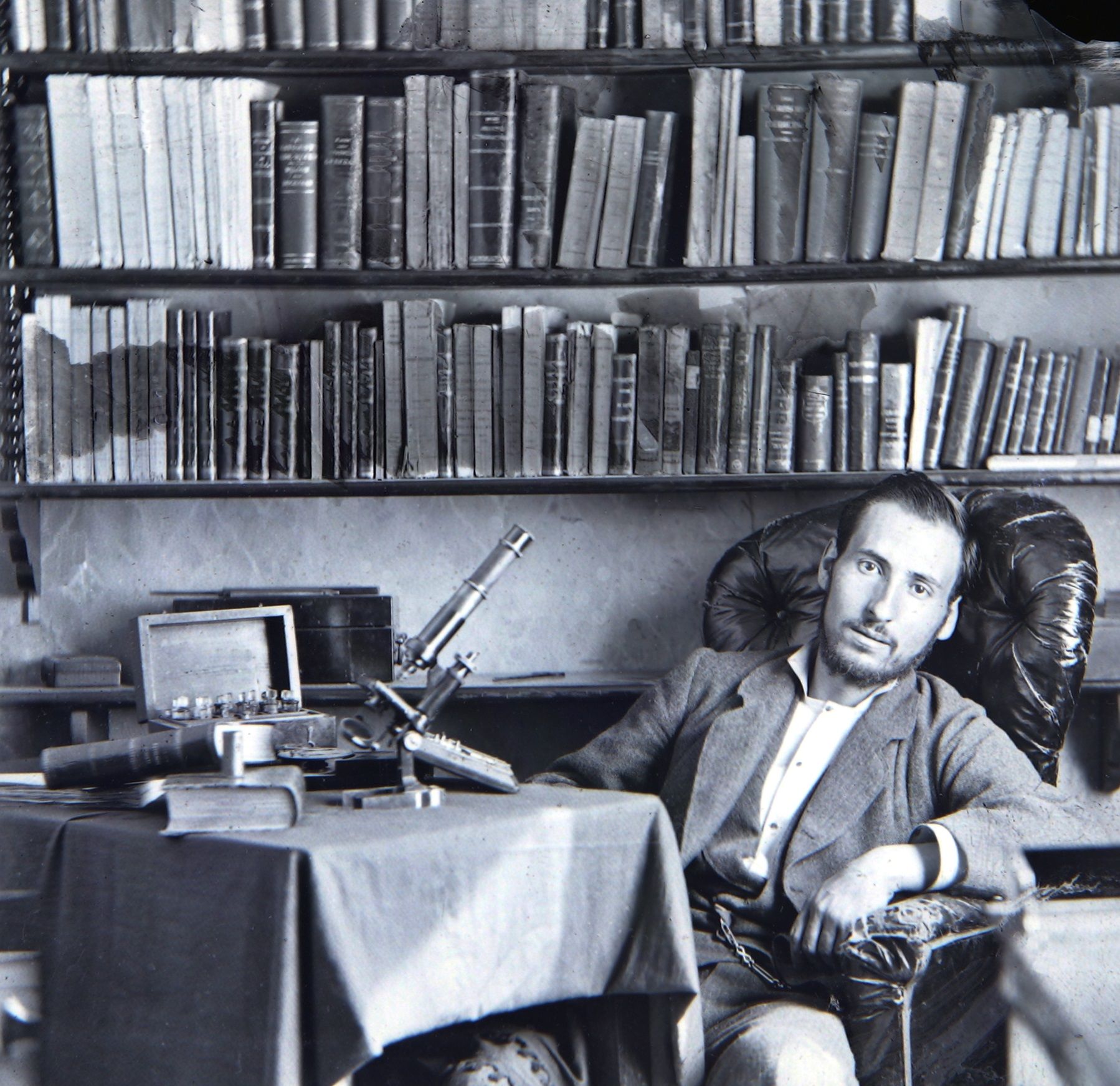

At that time he obtained his doctorate and, under the influence of Professor Maestre de San Juan, he became interested in Histology (the part of Anatomy that deals with organic tissues) and bought, with enormous effort, a mycoscope to make progress in its study. He won the post of director of Anatomical Museums and began to publish scientific works, but had no luck in the competitive examinations for professorships in Saragossa and Granada. Seeking to improve his battered lungs, he travelled to the Pyrenees and became enormously fond of photography, where, among landscapes, portraits and still lifes, he found a unique field of experimentation: he became one of the pioneers of colour photography and a highly recognised innovator in this art.

Work

Married to Silveria Fañanás from Saragossa, in 1883 he obtained a professorship at the University of Valencia. In that city he read, wrote, became interested in hypnotism, played chess and, when a cholera epidemic broke out in 1886, he studied the work of Dr. Ferrer and wrote a report for the Saragossa Provincial Council. He won the chair of Histology at the University of Barcelona and in 1892 he took up the vacancy for the same subject in Madrid, where he settled permanently. By then he was already studying the nervous system in depth and his work received praise from the German Anatomical Society in Berlin. In Spain, his work, which had been completely ignored, gradually began to be recognised.

Cajal researches, publishes, attends international congresses at which his prestige increases. He was honoured at Cambridge and Harvard, among other universities, and in 1900 he received the prestigious Moscow Prize at the International Congress of Medicine in Paris. He joined the Royal Academy of Sciences and in 1902 he was appointed director of the recently created National Institute of Hygiene and the Laboratory of Biological Research (the forerunner of the Cajal Institute of Biological Research, in 1922, which would later be incorporated into the CSIC). His multiannual publication Textura del sistema nervioso del hombre y de los vertebrados (Texture of the nervous system of man and vertebrates) (1897-1904) is an impressive body of research.

The Nobel

Around 1903 he developed his research into the physiology of the nervous system. Based on the work of Camillo Golgi, whose microscope preparations he improved, he was able to see the endings of nerve cells (neurons) and demonstrate that they were independent units, moved by impulses (by chemical or electrical transmission, “synapses”). Thus, although the Italian researcher held a different position (“reticularist”, defending a more intertwined structure of neurons), the Aragonese valued this contribution despite the fact that his theories were fundamentally refuted. In fact, the Nobel Prize for Medicine (1906) was awarded to them jointly, although their personal relationship was null and Golgi did not recognise his colleague’s merits.

The year before the Nobel, Cajal’s work had been recognised with the Helmholtz Gold Medal of the Berlin Academy: an award which at that time was even more prestigious than that of the Swedish Academy.

President of the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios (which he directed until 1932), he never stopped researching, testing methods and innovating. An example of this is his work Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System (1912-1914). The European War filled him with sadness: for him it was the failure of reason and of the values that had always guided him. He created and maintained a school, with disciples of great academic and research experience. For him, all of this was much more important than the honours and the honours of the authorities (he had already been offered, unsuccessfully, the post of Minister of Public Instruction in 1907; later, he would be made a senator).

The father of modern neuroscience, whose research continues to reveal new clues and to stimulate researchers all over the world, died in Madrid on 17 October 1934, and was consecrated as a national glory, pining in his last years for Silveria, also devoted to sorting out his memories.

References

- José Luis Cano (2002): Don Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Zaragoza, Xordica.

- Francisco Cánovas (2021): Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Maestro, científico y humanista. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Ramón y Cajal en el desván de la sabiduría”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (156-161). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Great Aragonese Encyclopaedia on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/monograficos/biografias/santiago_ramon_y_cajal/default.asp

- Spanish Biographic Dictionary, Real Academia de Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/10967/santiago-ramon-y-cajal

- Alberto Jiménez Schumacher, José María Serrano (coord.) (2020): Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 150 años en la Universidad de Zaragoza. Zaragoza: Universidad, free access in https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/88353/files/BOOK-2020-019.pdf This is the catalogue of the exhibition with which the University of Saragossa celebrated in 2019 the 150th anniversary of Ramón y Cajal’s arrival as a student at what he always called his alma mater.

Teaching activities

Santiago’s childhood. The villages

The childhood of our protagonist takes place in different places because of his father’s postings as a rural doctor. Justo Ramón was working in Petilla de Aragón, a Navarrese enclave in the north of the province of Saragossa, when Santiago was born. But both the family and the childhood experiences of the future doctor are clearly Aragonese, with a strong presence of the lands of the Pre-Pyrenees.

Locate these places on a map of Aragon: Larrés – Luna – Valpalmas – Ayerbe – Jaca.

Which regions do they belong to?

Larrés (Alto Gállego) – Luna (Cinco Villas) – Valpalmas (Cinco Villas) – Ayerbe (Hoya de Huesca) – Jaca (Jacetania)

Two recommendations to learn more about the early years of Santiago Ramón y Cajal:

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal (2006): Recuerdos de mi vida (Edited by Juan Fernández Santarén). Barcelona: Crítica.

- José Luis Cano (2007): Cuando yo era un niño. La infancia de Ramón y Cajal contada por él mismo (Introduction, edition and notes by José Luis Nieto Amada). Saragossa: University Presses of Saragossa. Larumbe Chicos Collection.

Two recommendations to get to know Ramón y Cajal “in his own sauce”:

A unique contribution by Cajal

Ramón y Cajal has gone down in the universal history of science for his studies on the functioning of the nervous system and for his observations on the degeneration and regeneration, development and plasticity of this system. His theories are still today a reference in the research of neuroscientists on the complex inner world that each of us harbours inside our bodies (a world with much to explore and discover).

For Cajal, intellectual activity does not depend so much on the number of neurons as on the number of connections established between them: more important than quantity is the relationship, the dynamism between these microscopic elements. The importance of “innate capacities” is not so important, since these capacities can be exercised: with will and study, we can all shape our brains.

Since he was young, he himself had been concerned about his physical form (among other reasons to defend himself from some “bad guys” he met when he arrived at high school in Huesca) and he knew how important physical exercise is… and mental exercise. Hence, in addition to the body, he also cultivated hobbies that exercise and challenge the mind: his passion for chess, his incursions into the field of hypnotism, his interest in literature and philosophy, his eagerness to experiment and innovate photographic techniques?

Look up the meaning of the Latin expression “mens sana in corpore sano”. How does it relate to what you have just read?

Ramón y Cajal once said: “I am a microscope worker”. How do you interpret that, what terms would you relate it to?

For example: work, patience, humility, tenacity?

In your entrance speech to the Royal Academy of Sciences, you took the opportunity to explain how young people should be trained to become good scientists: with tenacity, patience, independence of judgement and intellectual curiosity. And also… with scholarships to study abroad. This brings us to another issue.

Let them invent? Yes, but so can we

The phrase that opens this statement is an expression by Miguel de Unamuno taken out of context and which has been stretched like a cliché about conformism and the scant entrepreneurial and research spirit in Spain throughout its history. Today, this is an old-fashioned phrase, but it must be recognised that investment in education and research, which is a sure asset with which it is easier to face the future… is still insufficient. The crises of the last fifteen years have slowed down a trend which, at the turn of the century, was on the rise. Today we are trying to overcome this situation, but it is not easy…

Look up the definition of “brain drain”. Search the internet for news in the press about this phenomenon in relation to Spain and, if possible, Aragon. Look for references about investment in research in Spain: where does it stand in Europe, how has it evolved? Look for any news regarding the situation of grant holders, those contracted in universities and research centres, the precariousness of their employment, comparison with other places abroad…

Science in Spain, science in Aragon… is not going through the best of times, it is true, although there have been much worse times and some progress has been made. Progress owes much to the efforts of the scientific people of the past. People whose main exponent is Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

In 1900, Spain had more than 60 percent illiterate people. The university, limited to a few, had a stale smell; the academic world was incapable of taking on board the scientific and technological revolution that other places were already experiencing. Cajal was a breath of fresh air. Thanks to him, part of the enormous backwardness that had existed for centuries was recovered and, in addition to being in contact with the vanguard of international science, research infrastructure was created. He was at the head of the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios: an ambitious project to regenerate and modernise the education system, with research training stays abroad as a key element.

There have been many others. Not everything is due to Cajal, of course, but his figure goes beyond the exclusively “researcher”, becoming a reference for management and public policy in relation to education and science. In the sense that he aims to help transform inherited inertias… Ramón y Cajal is a regenerationist.

Other Aragonese scientists and Aragon

More or less contemporaries of Cajal, between the mid-19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, there were men of science from Aragon (or who developed their careers in Aragon) who made very important contributions to the different branches of scientific knowledge.

Look for information about these people, find out a little about them, and associate them with the discipline in which they excelled:

- Zoel García de Galdeano a- Botany

- Julio Palacios b- Chemistry

- Francisco Loscos c- Geology

- José Pardo Sastrón d- Physics

- Lucas Mallada e- Botany

- Miguel Catalán f- Mathematics

- Bruno Solano g- Physics

Solutions: 1-f; 2-d (o g); 3-a (o e); 4-e (o a); 5-c; 6-g (o d); 7-b

This… What about scientists?

Find information about the International Day of Women and Girls in Science: when is it celebrated, what are its objectives?

11 February

Look for information on Blanca Catalán de Ocón, what was her distinguishing feature?

From Calatayud (1860-1904), she is considered the first Spanish botanist.

Look up information about these three women and find out what makes them unique: Antonia Zorraquino, Jenara Vicenta Arnal Yarza and Ángela García de la Puerta.

They were the first three women to obtain a doctorate in Chemical Sciences in Spain, at the University of Saragossa, in 1929.

Man of science and… humanist

In spite of the obvious the distances, Santiago Ramón y Cajal resembles one of those Renaissance types, like Leonardo, who hit all the right notes. In addition to his contributions to world science, this man from Aragon cultivated and practised athletics and gymnastics, drawing, photography and chess, studied hypnosis and philosophy, cultivated literature and was concerned about the world around him. However absorbing his work may have been, he does not conform to the cliché of the “absent-minded, self-absorbed, out-of-this-world sage”.

It shows how artificial it is to label and speak of “sciences” and “letters” as watertight compartments, how simplistic it is to differentiate between natural and experimental sciences on the one hand, and social sciences and humanities on the other.

In the scholar’s literary work, we can highlight his autobiographical books Recuerdos de mi vida: Mi infancia y mi juventud (1901) and Recuerdos de mi vida: Historia de mi labor científica (1917), which he would later republish. He also published Cuentos de vacaciones (1905), in which he took up writings from his youth, and Charlas de café (1921), as a leisure and escapist activity. He also wrote essays such as La psicología de los artistas (1902), Psicología de Don Quijote y el quijotismo (1905) and La fotografía de los colores. Scientific Bases and Practical Rules (1912).

In his last work, El mundo visto a los ochenta años: impresiones de un arteriosclerótico (1934), Cajal makes an ironic analysis of the world in the last days of his life, and despite his demoralisation with what he sees, he never abandons his hope for man and progress.

In his foreword he shows a significant degree of self-criticism and humour:

If the learned public likes these literary trifles, the present series will be followed by another to complete the dozen tales; if, on the other hand, and it is to be presumed, my scientific sermons and outdated lyricism do not find grace in their eyes, the rest of these compositions will sleep the sleep of ill-fated ghouls, which must be much deeper than the so-called sleep of oblivion.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal in popular (TV) culture

In the 1980s, Santiago Ramón y Cajal acquired a certain popularity thanks to a high quality television series, which was widely followed (in those days there was not as much audiovisual offer as there is now). It was Ramón y Cajal (historia de una voluntad), directed by the Aragonese director José María Forqué, starring Adolfo Marsillach and Verónica Forqué, and broadcast in 1982.

Mr Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: