Miguel Servet

Martyr for freedom of conscience

Villanueva de Sijena, 1511 – Geneva, 1553

The son of the notary Antón Serveto, from a noble family, Miguel showed talent and application for the arts from an early age: he learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew at the abbey of Montearagón and later studied law and theology in Toulouse. Called by his relative Juan de Quintana, who was to become confessor to Charles I, he accompanied him as a page and secretary in Germany and Italy. In 1530 he attended the coronation of King Charles as emperor in Bologna: such ostentation seemed to him unworthy of the true Christian spirit. He was also with Quintana in cities such as Granada and Valladolid (where he attended Inquisition trials) and attended the Diet of Augsburg, where he saw the impossibility of understanding between Catholicism and Lutheranism.

Life

The Reformation, which was being proclaimed by sections of the clergy, was already a fuse that had been lit in Europe. Servet felt close to the moderate proposals of Erasmus of Rotterdam. He had met reformers in Toulouse: he was interested in their ideas, but he did not agree with them, raising questions, questioning many things and not believing anything at all. In his early twenties, he travelled to cities in Central Europe, met the reformers Oecolampadius in Basel and Bucer in Strasbourg, and persuaded a printer to publish his theological treatise Seven Books of Errors on the Trinity. The book unleashed the wrath of Protestants and Catholics alike. From Spain, the Inquisition tried to get him to hand himself in for trial. The Aragonese not only did not recant, but in Dialogues on the Trinity and on Justice in the Kingdom of Christ he reaffirmed his theses: he recognised one God, but denied the dogma of the Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit), of which he saw no reference in the Bible, and maintained that Jesus, the Son of God, was human, an intermediary for man to know God.

After meeting the reformist John Calvin in Paris, with whom he soon clashed, he changed his name and, as Michel de Villeneuve, settled in Lyon, where he worked as a proofreader in a printing house. He acquired knowledge of medicine and philosophy and gained prestige with reprints such as Ptolemy’s Geography. He studied medicine in Paris, where he learnt anatomy with Vesalius, practised dissection and wrote about syrups.

In the French capital he taught Geography, Astronomy and Astrology. Heterodox to all, his Discourse in favour of astrology unleashed new anger (his book was burnt), he travelled to Montpellier to further his studies and resumed his relationship with the printers of Lyon; he edited and corrected scientific books and bibles for them. He practises as a doctor in Charlieu and, from 1540, in Vienne in the Dauphinate. There he was naturalised as a Frenchman.

He lived quietly in Vienne, but did not give up his plans. Calvin, who was already the political and religious leader in Geneva, sent him his book Christian Institution, and the Aragonese sent it back to him full of erasures and annotations, together with a copy of his book Restitution of Christianity (secretly published under the initials MSV), which ended up by alienating him from the reformist leader. In this work, Servet insists on his theories against the dogma of the Trinity, explains that everything that exists in the world emanates directly from God, considers that man is incapable of sinning until the age of twenty and that the sacraments (only baptism and the Eucharist are indispensable) should be administered from that age onwards. He proposed the abolition of bureaucracy and hierarchy in the Church, with a more direct contact of the believer with God.

Work

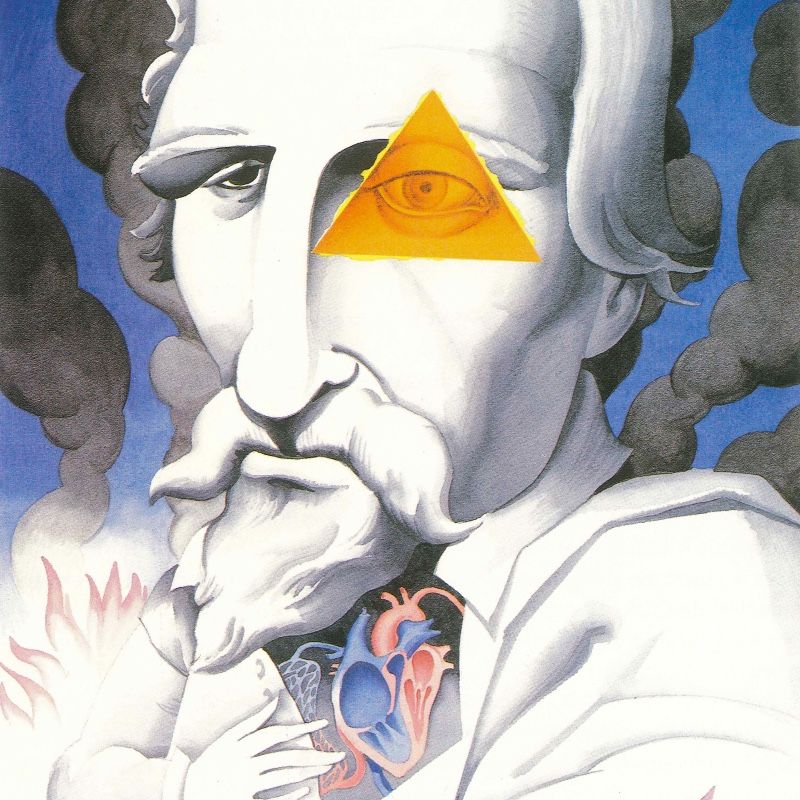

Servet’ work is a hymn to religious tolerance. He shares arguments with different Protestant factions, but is viewed with suspicion (and even hostility) by many of their leaders. In the Restitution of Christianity he describes the minor or pulmonary circulation of the blood. For Servetus, the soul resides in the blood and as it passes through the lungs it is revitalised by the spirit of God, which is in the air.

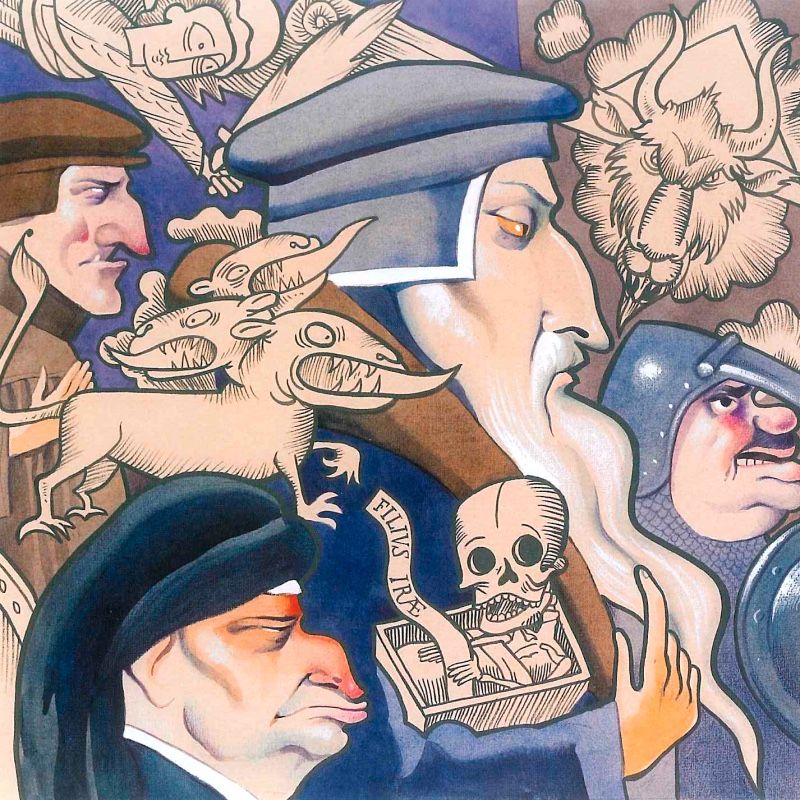

All this was a scandal to many. The ideas put forward by Servet in his greatest work were condemned, and his copies were seized and destroyed. The question of the anonymous authorship was soon cleared up because of the copy sent to Calvin some time before.

Servet was arrested in Vienne, but managed to escape. Sentenced to death, a mummy of him was burned in Vienne along with his books. After four months of being unaccounted for, he was recognised in Geneva and betrayed to Calvin. Tried as a heretic in an irregular trial, a court condemned him to death at the stake. On 27 October 1553, in the Geneva district of Champel, one of the champions of freedom of conscience was burned at the stake amid great suffering.

References

- Obras Completas, in six volumes, edited by Ángel Alcalá, between 2003 and 2006 by Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

- José Luis Cano (2002): Miguel Servet y el doctor de Villeneuve. Zaragoza: Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Miguel Servet o la transparencia del mal”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (66-71). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/monograficos/biografias/miguel_servet/default.asp

- Podcast of the programme “Acontece que no es poco”, by Nieves Concostrina on SER dedicated to Servet.

Teaching activities

Servet time

Servet lived in a period of great change. The first half of the 16th century saw the consolidation of trends outlined in previous centuries, which would lead the transition from the Middle Ages to the Modern Age.

Look up these definitions: Humanism – Renaissance – anthropocentrism.

Humanism, linked to the Renaissance as a cultural and artistic movement, overcame the approaches of medieval scholasticism: man now became the centre.

Feudalism gave way to the formation of strong, centralised powers and the kings imposed themselves on the lords, but rather placed them at their service. Authoritarian monarchy became the general concept of power, and the Church became a strong ally.

Despite this consideration that God is no longer at the centre of everything, there remains a decisive alliance between political authority and religious power. Even if they are sometimes in competition, both powers are aware that they need each other.

In addition to the global perspective built up by contact with a new world on the other side of the Atlantic, the field of mentalities was greatly stimulated by the invention of the printing press. The flow of knowledge and the exchange of ideas gained speed and reached more people. This greater access to culture meant that many dogmas were challenged and, with them, certain instances of power.

Currents of religious thought arrived from northern Europe, rethinking some of the doctrines of Catholicism. Without confronting them, Erasmus of Rotterdam promoted a religiosity far removed from ceremonies, personal, based on the simplicity of the origins, faithful to the scriptures. Erasmus was very influential… not only on Servet. In the kingdom of Aragon (which had already had contact with Italian humanism), many scientists and thinkers were attracted by his ideas.

In it, you can read brief biographies of Juan Sobrarias, Gaspar Lax, Pedro Sánchez Ciruelo, Fernando de la Enzina, Miguel Mezquita and Miguel Donlope. What disciplines did they excel in, and what consequences did holding opinions outside the official and authorised have on their lives? Delve a little deeper into the life of one of them, whichever one you prefer.

Erasmus will open one of the channels through which the German friar Martin Luther and others, such as John Calvin (our protagonist’s declared enemy, and in what way), will circulate with greater noise.

The Protestant Reformation. A religious… and political issue

In 1517, the Augustinian Martin Luther nailed to the door of the church in Wittenberg (where he taught theology at the University of Wittenberg) sheets of paper with the so-called “ninety-five theses”, in which he questioned the practices of the Church, denounced the luxury and corruption of its hierarchy, questioned many dogmas, and invited debate.

Cite the main ideas reflected in Luther’s theses.

Luther opposed the power of the Pope and his monopoly on the interpretation of the Bible. He calls for the reform of the curia, the abolition of celibacy and the abolition of the sacraments (except Baptism and the Eucharist).

The document was widely distributed thanks to the techniques of printing and distribution. The Catholic Church, accustomed for centuries to participating in temporal power and administering influence, took a dim view of this challenge, which, in reality, also affected the political powers in place.

Many German princes took advantage of the situation to oppose the emperor. That dignity was in the hands of Charles, the hereditary head of the Spanish monarchy and the German Empire. Attempts to bridge the gap (such as the Diet of Augsburg) failed, and many thinkers (Servet himself, as we have seen) were attracted to the Reformation. But many of them (Calvin and others) also fell into dogmatism and the belief that they alone were right.

Europe was to be embroiled in religious wars for decades. In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg established that each German prince could choose his own religion, which would be the religion of his subjects.

The theological response to the Reformation came from the Catholic Church itself: the Council of Trent (1545-1563) sought to clarify doctrinal and organisational points, correct abuses and improve the training and moral care of the clergy. But it failed to build bridges with the reformers: the Counter-Reformation would emerge from Trent, the Church became more inward-looking and repressive mechanisms such as the Inquisition Tribunal were strengthened.

The coronation of Emperor Charles

As has been said, the young Servet was shocked (negatively) by the pomp and pageantry surrounding the coronation of Emperor Charles in Bologna, with the submission of a Church which he saw as far removed from the true Christian spirit.

This event had a very notable artistic manifestation in a place worth visiting: Tarazona. Its town hall, a magnificent Renaissance palace built in the mid-16th century, displays a frieze depicting this event.

And if you can see it live, so much the better. This Aragonese city and its surroundings, in the vicinity of the Moncayo, have many things to see.

Misunderstandings about its origin

There are still some biographies of Miguel Servet in which his birth is placed in Tudela (Navarra), and it is also dated in 1509. But no: Miguel Servet Conesa was born in Villanueva de Sijena in 1511. The misunderstandings are due to the fact that he himself was forced to play a game of deception in his eventful life, hiding under pseudonyms and acronyms in the authorship of polemical texts that could cause him problems, imposing names and placing false data in judicial processes… Thus, we find references such as Michael Servetus, Michael Villanovanus, Michel de Villeneuve or M.S.V.

What he also did was to remove the final “o” from his surname (Servet, a place in the Chistau valley where his family came from). For a time it was also thought that this game of hidden identities was due to a Judeo-Converso origin that he considered it appropriate to hide, but this does not seem to be the case, despite the fact that his maternal branch did have links with the Zaporta lineage.

Another essential visit: Villanueva de Sijena. The town where Miguel Servet was born has a monastery which has gone through enormous vicissitudes and which is well worth a visit today. And of course, the house where our protagonist was born, which is the headquarters of the Miguel Servet Institute of Sijena Studies:

The Pulmonary Circulation of the Blood / Servet, persecuted even after death

Servet has gone down in history for something that, in reality, was secondary to his work and thought. Perhaps that is why it went unnoticed for centuries. In Book V of the Restitution of Christianity he describes the minor or pulmonary circulation of the blood: the blood is propelled from the heart to the lungs (through the pulmonary arteries), where it is oxygenated and returned through the veins to the heart; from there it is distributed to all parts of the body to return once the oxygen concentration has dropped and restart the cycle.

It may seem strange that an anatomical process is described in a treatise on theology. According to the Bible, the soul is in the blood, injected by God through the breath. Servet believed that in order to understand the human soul, one must first understand how the blood circulates through the body.

In the 13th century, the Egyptian physician Ibn an-Nafis had anticipated this theory. His manuscript, forgotten for

centuries, is recorded to have been in Venice in 1521, and may well have been known to Servet a little later. Servetus, after all, was the first to describe this process in the West. However, the credit would later go to the Englishman William Harvey, who had made the same description in 1616 (several decades after Servet’s death). It would be the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz (one of the great rationalist thinkers of the 17th century) who would recover the memory of the Aragonese. Even after his death, Servet was haunted by the air of a cursed and clandestine man.

After his death, the Calvinist authorities, the Catholic and Protestant inquisitors in France and Germany tried to destroy all of Servet’s work. In some clandestine circles (Basel in Switzerland, Padua in Italy…) an attempt was made to preserve his legacy. Only three originals of the Restitution of Christianity (of the eight hundred that were printed) have survived to the present day. The Enlightenment writers of the 18th century, with Voltaire at their head, claimed him as a champion of freedom of conscience.

Servet nowadays

Miguel Servet is a true humanist, interested in a wide range of knowledge, always ready to learn and to experiment. To this he adds courage, firmness (which some might call arrogance and insolence), certainty in his approach even when expressing his many doubts. Coherence and faith in his right to freely express his ideas would end up costing him his life, but they reserved a place for him in posterity.

Today, the merits and genius of Miguel Servet, who gives his name to the main hospital complex of our autonomous community (the one that many people from Saragossa still call “la Casa Grande”), are recognised. As Ángel Alcalá says, “to ignore him is a crime against the Aragonese homeland”.

Look for references to Miguel Servet in different everyday spheres, in Aragon and outside Aragon (streets, awards, monuments, etc.).

Miguel Servet and the doctor from Villeneufve

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of Ibercaja’s Obra Social.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: