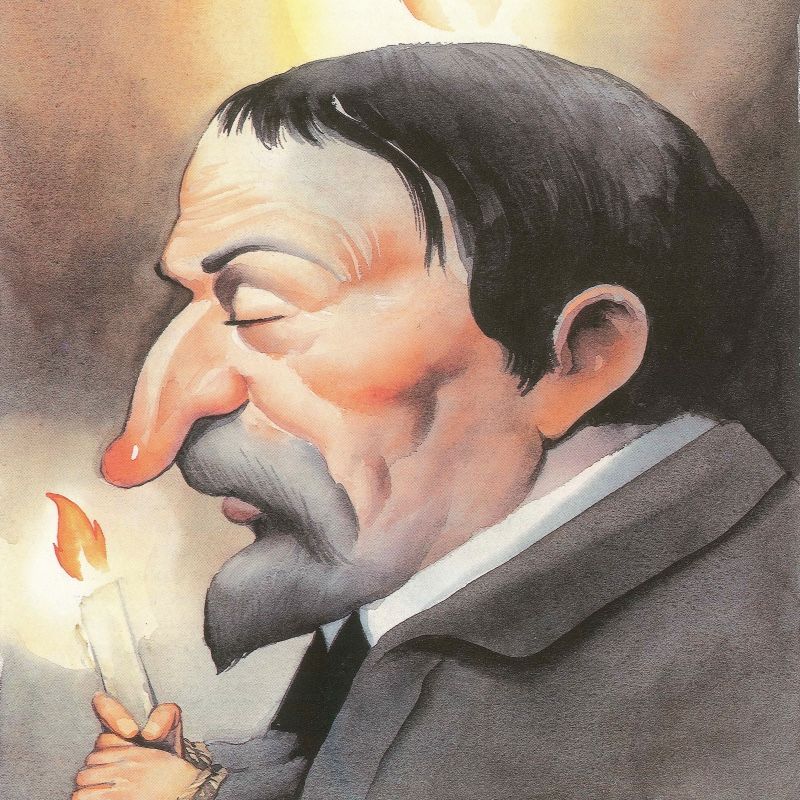

Miguel de Molinos

Free and self-absorbed spirit

Muniesa, 1628 – Rome, 1696

Miguel de Molinos continued in a peculiar line of Aragonese heterodox led by Miguel Servet. His end was not as violent as that of Servet, but it was dramatic and slow-motion. All for defying dogma and upsetting the powers-that-be, even if that was not his aim.

Born “among olive groves and rye in the Muniesa moors” (as Antón Castro says), and after a childhood and adolescence of which very little is known, the young Miguel, son of Pedro Molinos and Ana María Zujía, settled in Valencia, benefiting from a scholarship granted by the church of San Andrés. In the Levantine city he studied at the Jesuits, studied theology and was ordained a priest in 1652. He was a confessor to nuns and a member of the School of Christ, a very strict congregation devoted to spiritual reflection.

Life

In 1663 he was sent to Rome by the Provincial Council of the Kingdom of Valencia as a delegate to speed up the beatification of the Valencian priest Francisco Jerónimo Simó. He never returned from the Eternal City. There he joined the Roman delegation of the School of Christ and began to gain fame as a great preacher and spiritual director of prominent personalities, including women of high society. As an ascetic and “enlightened” man, he practised an austere lifestyle in pursuit of moral and spiritual perfection.

Preceded by a Brief Treatise on Daily Communion, in 1675 he published the Spiritual Guide which disburdens the soul and leads it on the inner path to perfect contemplation and the rich treasure of inner peace. This work already says a lot in its long title. For Molinos, the soul must be pure, without sin, far from worries and meditations. This spiritual emptiness, this nothingness, is the shortest way to God. Some see in these doctrines a kinship with Buddhism and the search for nirvana.

Work

The Spiritual Guide met with the approval of theologians (several of them censors of the Inquisition) and in later years it was translated into Spanish (in several editions, one of them in Saragossa), Italian, French, Dutch, English, German and Russian. Molinosism and its “quietist” methods gained followers.

At first, these doctrines met with no opposition, but soon the tables began to turn. Molinos had written Letters to a disillusioned Spanish gentleman to encourage him to have mental prayer, giving him a way to perform it, trying to correct some points that he perceived were not being well interpreted in his Spiritual Guide. But that was not enough, because his doctrines annoyed very powerful people in Rome and in Christendom.

Relentless attacks

The Jesuits felt that, in his defence of contemplation over meditation, Molinos was disparaging their founder Ignatius of Loyola and his Spiritual Exercises. Molinos was accused of initiating “any nun or woman” into the contemplative system (lofty and complex and only within the reach of “a few privileged souls”). This explains a lot. What bothered the Jesuits was that not a few convents of nuns had moved from Jesuit direction to Molinassian methodology.

The influence of the Society of Jesus was being tested and its shadow was very long. Some Jesuits began to launch relentless attacks and to point directly at him as a heretic. Molinos wrote his Defence of Contemplation without much success, because both it and the Spiritual Guide were included in 1681 in the Index of books banned by the Holy Office. Pope Innocent XI, despite his friendship with Molinos, yielded to these pressures.

The Quietist doctrines were put on trial, considered a cancer spreading through Spain and France. Molinos was arrested in the summer of 1685. The trial was slow because it was not easy to obtain proof of the Aragonese priest’s alleged doctrinal deviations. Under torture, he admitted absurd accusations of immorality and abjured his doctrines. Humiliated and sentenced to life imprisonment, he died on April Fool’s Day 1696. His figure and his work (an innovative spirituality based on the experience of the individual) were to be recovered well into the 20th century.

References

-

Here are some of them.

- Antón Castro (1993): “Miguel de Molinos. El tormento de la nada”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (108-113). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miguel_de_Molinos

- Jesús Ezquerra (2014): El profundo de la nada. El desapego de Dios en el místico aragonés Miguel de Molinos. Zaragoza, IFC.

- Francisco Martín, Miguel Ángel Motis (2019): Miguel de Molinos. Heterodoxia, mística y escritura. Muniesa-Utrillas, Centro de Estudios Miguel de Molinos, Comarca Cuencas Mineras.

Teaching activities

Mysticism

As you can see, these characteristics coincide with what we know of his life and thought. Miguel de Molinos continued a long mystical tradition, which had been strongly established in the Hispanic territories for centuries. Mysticism not only corresponds to the Christian world, but also has significant Muslim and Hebrew exponents.

Look up information on these terms: Sufism / Kabbalah

The mystical tradition is covered by different faiths and religious confessions. It often wanders on the fringes and runs the risk of being regarded as dangerous if there are such rigorous and strict advocates of dogma that alternative or slightly ‘different’ views are seen as directly attacking the core of the faith.

Look up the definition of dogma: Do you think dogmatism is contrary to freedom of thought? Write a short explanation of these questions in a few lines. The biography of Molinos may help you to exemplify this, but also the entries we have on this website about Miguel Servet and (though not so crudely) Baltasar Gracián.

Before Molinos, many religious men had followed the Christian mystical path that St. John of the Cross and Santa Teresa of Jesus personify so well (and with great literary quality). These two authors were glorified and canonised even though they said things that could have been interpreted in a twisted way. In fact, they were not without problems during their lives either, and often encountered censorship and intolerance.

Although the author died in 1591, this work was not published until 1630. Why do you think this is? Do you think that the poems of the Spiritual Canticle are very religious according to “the rigorous”… or perhaps the ways of expressing them indicate something else?

Some clues: this poet speaks of love, beauty, recreation… assimilating them to the divine. This (and other things) got Juan de la Cruz into trouble in his order, the Carmelites, and cost him prison… although he was finally able to develop his work.

As Martín and Motis say, the mysticism of Miguel de Molinos “had nothing that had not received the approval of the Church in the writings of the great Spanish mystics and Saint Francis de Sales, abandoning all apparatus of ecstasy and visions, very abundant in the writings of Santa Teresa, reducing his path of perfection to the Brahmanical ideal of the annihilation of sense and understanding, mystical silence or death, where word, thought and will vanish and God speaks to the soul and teaches it the highest wisdom”.

But the priest from Teruel did not receive the approval that other mystics did. Not only that, but he was severely punished. The approach to divinity through contemplation as annihilation and recollection, the prayer of stillness, the suspension of speech and understanding… all of this would fall under theological suspicion. Molinos’ misfortune was that his popularity, the success of his doctrines, attracted envy in the papal curia, driven by political interests.

The Society of Jesus wielded immense power in Rome and in much of Christendom. Its influence was immense in doctrinal and educational matters, and Molinos’ closely followed doctrines were an obstacle. This explains the furious attacks that led to his prosecution. The Spanish Inquisition welcomed the condemnation of Molinosism (which was widespread in France, Italy and Spain) and its leader and followers.

Perhaps, in rejecting and punishing Molinos’ quietist doctrines, the Catholic Church missed an opportunity to move closer to a more universal understanding of religion.

A parallelism, “real” relations and influences by Miguel de Molinos

Another illustrious Aragonese in Rome

A few decades earlier, another Aragonese, this one from Peralta de la Sal, had left an important trace in Rome. José de Calasanz (1557-1648) is one of the great names in the history of pedagogy. It was in the city of the popes that he undertook the initiatives that bore fruit in the creation of free and popular schools. The founder of the Pious Schools, friend and supporter of Galileo and Campanella, had also clashed with the Jesuits, who did not take kindly to alternatives to their educational monopoly.

Explore the biography of Saint Joseph Calasanz and summarise his contributions to the history of education.

Christina of Sweden, a different queen

Miguel de Molinos maintained an intense relationship, especially epistolary, with the former Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689). A woman of great intellectual restlessness (in her youth she had called the philosopher René Descartes to her court in Stockholm), after her abdication and subsequent conversion to Catholicism, she had lived between Rome and other European cities. She had been noted for her freedom of thought (which attracted a great deal of criticism in the very conservative Roman milieu) and was attracted by the quietism proposed by Molinos.

Christina of Sweden is a very interesting character because she broke many moulds in her time. She swam against the tide on very sensitive issues (such as religion, by renouncing the strong Protestant tradition of her dynasty, or the gender and affective-sexual roles she challenged). Explore his biography a little. There is an all-time cinema classic: the film Queen Christina of Sweden (1933). It has a rather sweetened romantic plot, but just to see the way the great actress Greta Garbo fills the screen… it’s worth it. It is easily accessible on different platforms. More recently, from 2015, the Canadian film Queen Christina Red Arms (based on the play La Reine-Garçon) also focused on her figure.

Influential author

Miguel de Molinos has influenced the literary works of Ramón María del Valle Inclán (who in his book La lámpara maravillosa deals with questions related to reincarnation and karma) and Ramón J. Sender (especially in his novel El verdugo afable). Also, very clearly in María Zambrano (she speaks of nothingness as a “creative exercise”, seeking the ideal in truth). This great philosopher, who reflected on the relationship between the divine and the poetical, takes up the ideas of the Aragonese thinker in many of her books (including Claros del bosque) and published an article entitled “Miguel de Molinos reappeared” (Ínsula magazine, 1974), in which she asked: “Is it not that poetry is always paired with mysticism, that it is itself in a certain way a mystic?

Quietism has been locked up in a cliché that is not accurate: its almost exclusive identification with Eastern thought. According to Tellechea, Molinos is the pioneer of free thought and the father of modern rationalism; he is a theosophist related to the East (…), he is the peak of Spanish mysticism (…) and represents an Aragonese way of being a heretic”.

Almost by way of conclusion… looking at all this with 21st century eyes, it is not easy to understand how the details and nuances surrounding questions that are so intimate at heart (the soul, self-knowledge, inner peace…) could raise so many passions, lead to death or imprisonment for those who strayed from dogma, although they did not question the authentic subject of faith at all. In class you can compare and discuss conflicts and situations that today may remind you of those of the past. The topic has many, many readings.

Molinos, recovered

From Muniesa, his native town, the figure of Miguel de Molinos, who gives his name to a Study Centre, is also being vindicated. This cultural entity, attached to the Instituto de Estudios Turolenses, tries to recover the memory of one of its most illustrious sons.

We have selected four sentences that give way to some of the first chapters of the main work of Miguel de Molinos, the Spiritual Guide.

- For God to rest in the soul, the heart must always be pacified in any restlessness, temptation or tribulation.

- Even if the soul is deprived of speech, it must persevere in prayer and not be afflicted, for that is its greatest happiness.

- The soul is not to be afflicted, nor is it to give up prayer because it is surrounded by dryness.

- For the soul to reach the supreme inner peace, it is necessary that God purges it in his own way, because the exercises and mortifications that it can take by his hand are not enough.

The word “soul” appears in all four sentences: why do you think he gives it so much importance, do you think the message is optimistic or pessimistic, does he give hope, does he give advice, does he point out obstacles and inconveniences, does he think they can be overcome?

Although little known, it can be said that Miguel Molinos can be appreciated today because he addresses universal questions that have concerned human beings since the beginning of time. Whether you are a believer or not… there is always a part of us that at some moment, however fleeting it may be, seeks a transcendent explanation, a small light, a connection with an ideal something… “And poor man in dreams / always looking for God in the mist”, said the great poet Antonio Machado (poem “It is an ashen and misty afternoon”, in Soledades, Galerías y otros poemas, 1907).

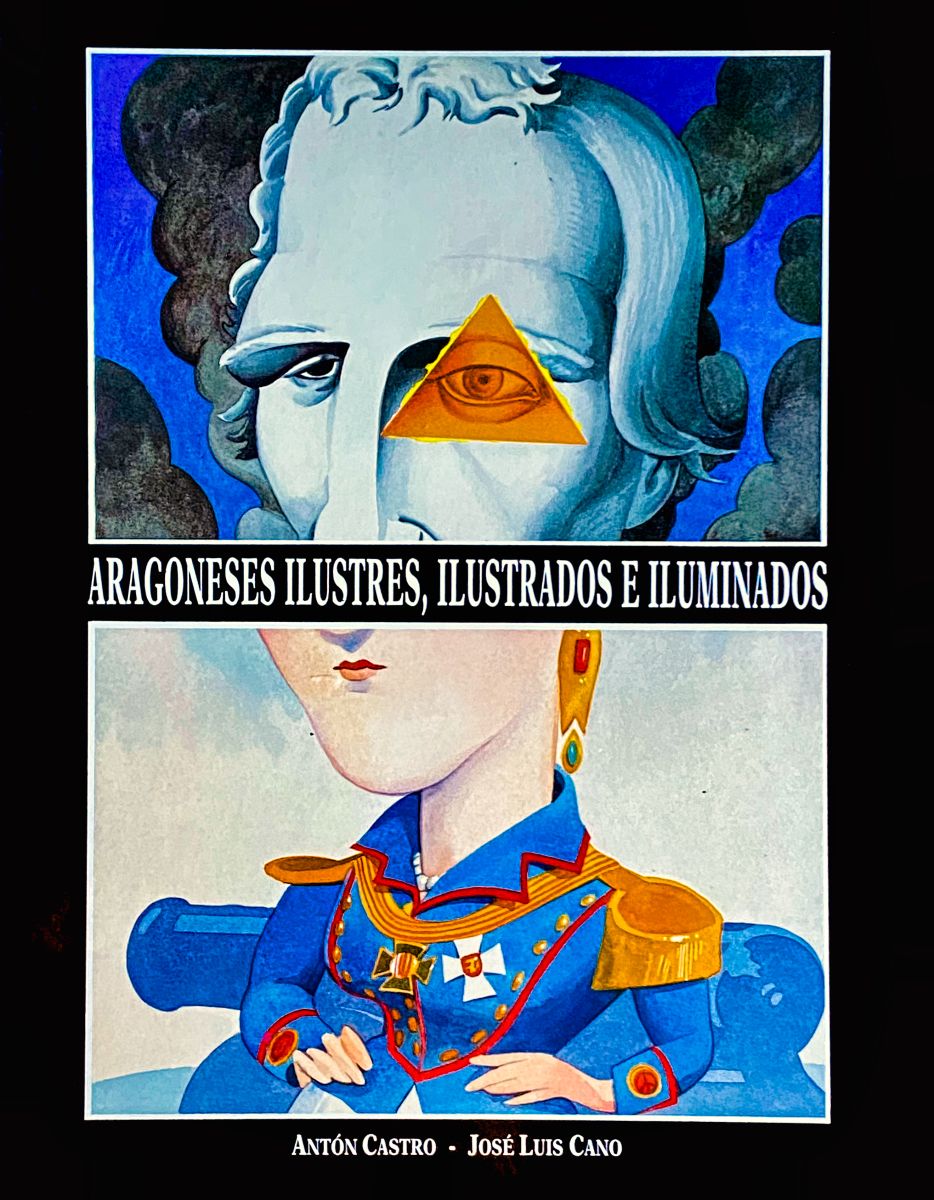

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: