María Moliner

The woman who deciphered all the words

Paniza, 1900 – Madrid, 1981

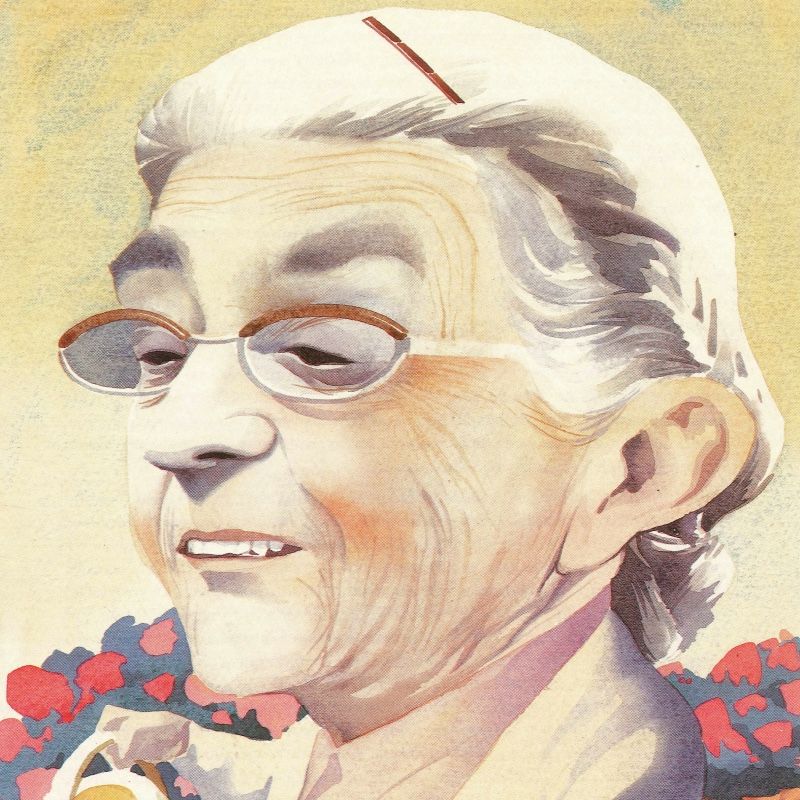

When the name María Moliner is mentioned, almost no one knows who we are talking about. Only those who are dedicated to the world of letters have heard it mentioned and instantly identify it with a dictionary, a useful but boring type of book, often “difficult to decipher” and which not infrequently clarifies little of what it is intended to find out. However, this name is not only the title of a “different” reference work, as useful as it is entertaining. It was also the name of its author, a fascinating person of flesh and blood who fought selflessly all her life, without giving up, even when circumstances were against her, to raise the cultural level of her fellow human beings so that they could prosper in life.

Life

María Moliner Ruiz was born in 1900 in the town of Paniza in Saragossa, the daughter of a country doctor. When she was four years old, her father joined the navy and the family settled in Madrid. In the Spanish capital, María and her siblings began their education at the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, a novel, private, secular educational project that emerged at the end of the 19th century.

In 1914, on one of his visits to Argentina, the head of the family, who was travelling as a ship’s doctor, decided not to return. This marked the beginning of a complicated period for María and the rest of her family. They settled in Saragossa and to earn some money María began to give private lessons, even though she was still almost a child.

Work

Economic difficulties did not prevent her from continuing her studies and she was one of the few women who at that time went to university. She studied Philosophy and Letters, specialising in History, the only one there was at that time in Saragossa. She was involved in the preparation of an Aragonese dictionary (as part of a project, the Estudio de Filología de Aragón, led by Juan Moneva and supported by the Diputación de Zaragoza), which was never published, and she immediately obtained a position in the Simancas archive in the province of Valladolid, where she remained until 1924, when she obtained a better position in an archive in Murcia. In that city she met the physicist Fernando Ramón, one of the university professors who introduced Albert Einstein’s theories to Spain, and married him.

A few years later the couple moved to Valencia, already with several children. Concerned about their education, he joined with several married friends to create one of the most advanced schools of its time, the Cossío School, similar to the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, of which María had excellent memories. At this school she taught Grammar and Literature.

Pedagogical missions

In the early days of the Second Spanish Republic, established in 1931, education was intended to be the engine of progress and social advancement. Hundreds of schools and institutes were built, teacher training was improved and the so-called Pedagogical Missions were created to bring art, theatre, cinema and books to the rural world. María Moliner was enthusiastically involved in all these initiatives. She took part in an international congress on libraries in 1935 and drafted instructions to help librarians in small towns. However, a year later, the Civil War broke out and the whole project collapsed.

In the middle of the war, she was appointed director of the University and Provincial Library of Valencia, which became the provisional capital of the Republic, as Madrid was under siege. She prepared a plan to organise all the libraries in the country. But the Republicans lost the war and nothing could be done. The Institución Libre de Enseñanza and the Cossío School were dissolved in favour of a traditional Catholic education. Many of her friends were executed, imprisoned or went into exile. And María and her husband suffered severe reprisals. Fernando Ramón was imprisoned in Murcia and his job and salary were taken away. Because María was well spoken of by some of the leaders of the winning side, she was allowed to work, although she was demoted. From being one of the country’s top educational leaders, she became just another librarian, with a humble salary.

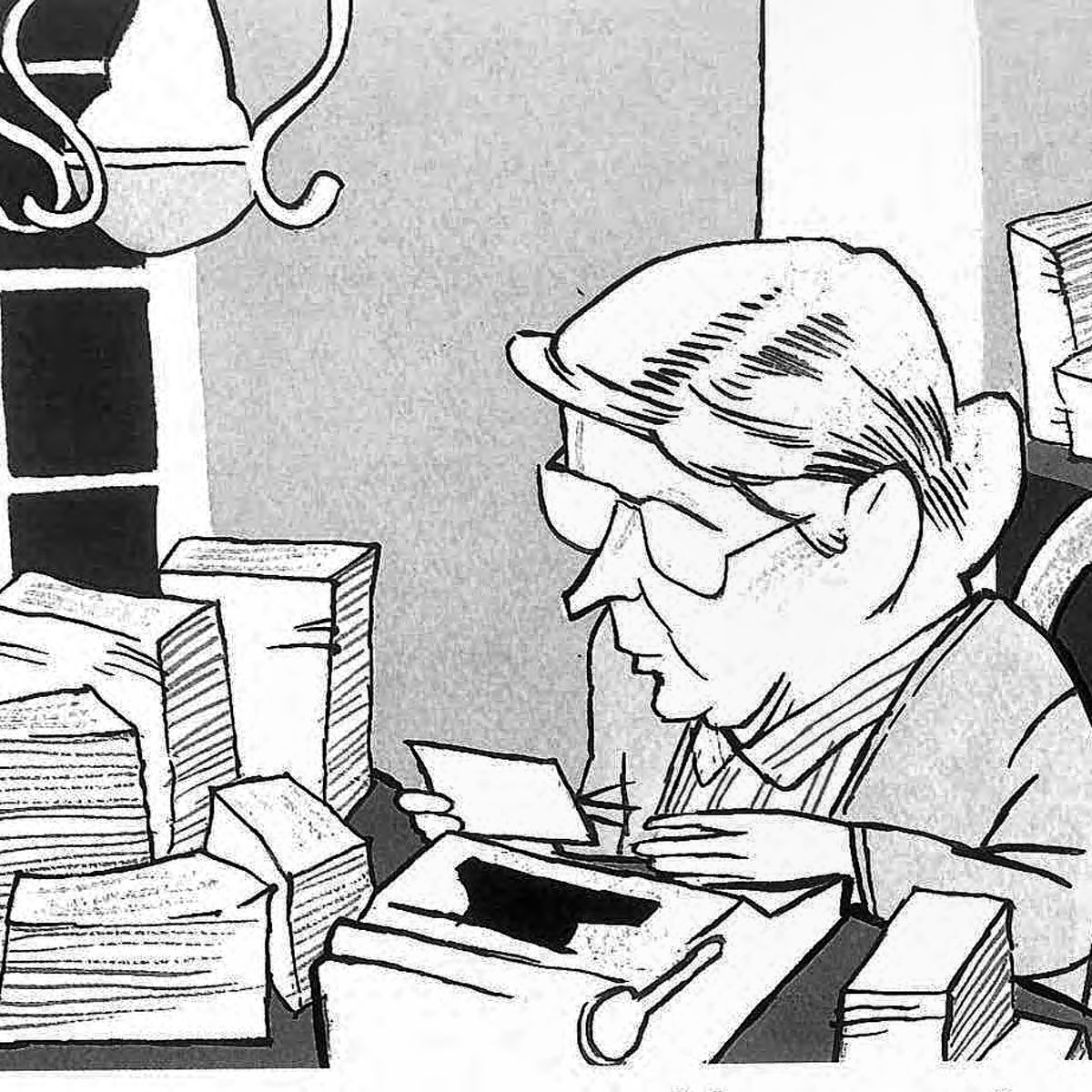

Years later, her husband was able to return to the University and was posted to Salamanca while María got a job in Madrid. Bored with her daily routine, with her children already grown up and far from her husband, whom she only saw at weekends, she had the idea of creating a dictionary that would help to improve the use of the language. And so she began her task.

At that time there were no computers or internet. So, in her spare time, armed only with her typewriter, pens and pencils, she began to write, without any help, thousands of sheets of paper containing all the existing Spanish words and their meaning. But not only the one established by the Real Academia Española but also the one used by people in the street, with plenty of examples and using simple vocabulary. He eliminated words that were no longer used and included others that were, even though they were not in the official dictionary, along with swear words and onomatopoeias. In addition, those that had a common root and origin were grouped into families to make them easier to understand.

After years and years of solitary and tenacious work, her Dictionary of Spanish Usage was published in 1966, which astonished everyone. How was it possible that a woman alone, in her own home, without being a specialist in the subject, could have written such a monumental and valuable work? It seemed an inexplicable miracle. Praise and admiration multiplied. Many felt that María Moliner should be a member of the Royal Academy, and in 1972 her name was put forward for membership of the institution. But no woman had ever done so. And neither had she. She was a woman and, moreover, a history graduate, not a philology graduate. The decision and the great controversy that ensued affected her. And it is quite possible that it accelerated the brain disease she was suffering from and which finally caused her death in 1981.

References

- Mª Pilar Benítez (2010): María Moliner y las primeras estudiosas del aragonés y el catalán de Aragón. Zaragoza: Rolde de Estudios Aragoneses.

- Hortensia Búa Martín (2012): María Moliner. La luz de las palabras. Madrid: HBM.

- Manuel Calzada (2013): El diccionario. Madrid: Artezblai.

- José Luis Cano (2000): María Moliner y su Diccionario. Zaragoza, Xordica.

- Antón Castro (1993): “María Moliner o el cultivo de las palabras”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (204-209). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Pilar Faus (1990): La lectura pública en España y el Plan de Bibliotecas de María Moliner. Madrid: Anbad.

- Inmaculada de la Fuente (2011): El exilio interior. La vida de María Moliner. Madrid: Turner.

- Diccionario Biográfico Español, Real Academia de Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/12970/maria-juana-moliner-ruiz

Teaching activities

Instructions to rural librarians

During the Second Republic, in the first half of the 1930s, hundreds of libraries were created in Spain, especially in rural areas, which until then had lacked artistic and cultural activities. In 1937 María Moliner wrote Instructions for the service of small libraries, with the aim of guiding and encouraging inexperienced librarians, especially those assigned to small towns, where everyone knew each other. In these instructions, he indicated to them that the success of the library depended to a large extent on their work, that of stimulating reading and knowing how to guide the reader. Giving each person the book that will interest them, capture their interest and make them want to read it again, according to their tastes and interests.

Read the following excerpts written by María Moliner and comment on them.

The librarian, in order to put enthusiasm into his task, needs to believe in these two things: in the capacity for spiritual improvement of the people he is going to serve, and in the efficacy of his own mission to contribute to this improvement.

A librarian will not be a good librarian if he invariably greets the stranger with words that those of us who have visited Spanish villages on a cultural mission have engraved in our brains by dint of hearing them: “Look: in this village they are very closed-minded: you can talk to them about going to the dance, football or the cinema, but… To the library…!

In your town the people are no more closed-minded than in other towns in Spain or in other towns in the world. Try talking to them about culture and you will see how their eyes widen and their heads nod, and how they invariably reply: “That’s what we need: culture! They sense, in fact, that it is culture that they need, that without it there is no possibility of effective liberation, that it alone will give them sufficient impetus to join the fatal march of human progress without the risk of being overturned: they also feel that the culture denied to them is just another privilege conferred on certain people with no intrinsic superiority over them, sometimes with no moral value at all, an effective superiority in the estimation of society, in economic position, and so on. And they revolt against this, which they vaguely understand, by asking for culture, culture, culture…

Reading a book or watching a film can take you to unknown worlds, to meet other people and other ways of life or to live exciting adventures. María Moliner also wrote

Education is the basis of progress; I consider that reading is even a spiritual right and that, therefore, any citizen anywhere should have at hand the book or books he or she would like to read.

Do you think that reading stimulates imagination and creativity? Do you think that having more education helps you get a better job and prosper in life? Argue your answers.

María Moliner’s dictionary and the opinion of great writers

The dictionary written by María Moliner was somewhat different from the one published by the Real Academia Española. The latter indicated how words had to be used correctly, whereas the Moliner’s dictionary also explained, with examples, how they were used in reality, how people used them in the street, even indicating colloquial or vulgar expressions. It did not impose rules but was a dictionary of usage. In this way, both those who spoke Spanish and those who wanted to learn it could better understand the meaning of each word and, moreover, handle it in an appropriate way.

Because of its characteristics, many writers preferred it as an aid when writing their literary works. Thus, Miguel Delibes said of it: “it is a work that justifies a whole life”. And Fernando Savater: “it was the only dictionary that could be handled in this country”.

On 10 February 1981, just a few days after María Moliner’s death, the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, published a letter in the newspapers in which he pointed out how much he owed María Moliner. He thought it was an extraordinary feat that she had been able to write alone, by hand, at home, without any help, a work that seemed to have been put together by a large group of renowned specialists with abundant resources and a large budget. According to the novelist, it was more than twice as long as that of the Real Academia Española and more than twice as good. He always needed to have at hand the dictionary written by the Aragonese, the “most complete, the most useful, the most thorough and the most entertaining of the Castilian language”, in which he had managed to capture the reality of a living language. This, as if it were sand, slipped through the fingers of the academics, who favoured obscure definitions and were reluctant to accept the use of new words until they were already rigid and worn out by use.

A few years earlier he wanted to meet such an amazing woman. He travelled to Spain believing she would be famous, but, to his great surprise, it turned out that few knew her. He finally managed to find one of her sons, who told him that his mother was very ill and was not receiving visitors. When María Moliner died, García Márquez said he felt as if he had lost a loved one. Someone who, without knowing it, had worked tirelessly for him. A unique person who “tried to grasp all the words of life on the fly” to make them available to all those who speak Spanish.

Do you know who Miguel Delibes, Fernando Savater and Gabriel García Márquez are? Search the internet for a summary of their literary careers. Also look up the title of some of their works. Have you read any of their works? What was their plot?

The world of words

If there is one thing that differentiates us from the rest of the living beings we know, animals and plants, it is language, the use of words, which allows us to communicate with each other and to elaborate complex thoughts. Things that do not have names do not exist, because without a word to identify them we cannot inform anyone of their existence.

In all languages, words have an origin, an etymology, and María Moliner liked to group them according to that origin. In her book, the thematic order took precedence over alphabetical order. Thus, for example, we could know that balón derives from bala or that cultura and cultivo have the same origin and, therefore, the same root.

Is it correct to say that a field remains uncultivated, and that a person is uncultivated?

Try to find out if the word “assassin” has any relation to hashish. Or if the word “inaugurate” is related to the augurs, soothsayers from Roman times.

Also search the internet for the origin of the words “paper”, “book”, “library” and “parchment”. To give you a hint: two of them are related to plants and the other two to ancient cities. Do you know why?

In each region, even within the same country with the same language, there are particular words used only by the people who live there. In Aragon there are quite a few, which are not understood by the inhabitants of other parts of Spain.

Match the words used in Aragon in the left column with the meanings in the right column.

Chipiar Desaguisado

Esbafar Calambre

Chandrío Chismoso

Encorrer Goloso

Laminero Barrer

Garrampa Perseguir

Escobar Perder el gas

A cordetas Limpio

Escoscado Mojar

Alparcero A caballito

Solutions: 1-i, 2-g, 3-a, 4-f, 5-d, 6-b, 7-e, 8-j, 9-h, 10-c

The Royal Spanish Academy and women

When María Moliner’s dictionary was published, it caused great admiration. Who was this woman who had written an entire dictionary? Praise followed one after the other, and there were even several academics who argued that the author should be a member of the Real Academia Española. Three of them, as stipulated in the regulations, proposed in 1972 that she should occupy a place that was vacant at the time. In the end, however, it was decided to choose a different candidate. Among the reasons given for rejecting her appointment was that she was not a philologist but a history graduate. Moreover, no woman had ever been a member of the Academy since it was created in 1713.

And the latter was true. The first woman whose name was put forward to join the Academy was the poet and playwright Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda. She tried in 1853, but, after intense debate, an agreement was reached that year to ban women from the institution. In later years, other women of real merit were mentioned, such as Rosalía de Castro and Concepción Arenal. But the doors of the Academy remained closed to women.

An exceptional case was that of the writer Emilia Pardo Bazán, whose works were among the most widely read in her time, both in Spain and abroad. She tried to become an academic on several occasions, in 1889, 1891, 1912 and 1914. But she never succeeded because of her status as a woman, despite the widespread support of the press and literary figures of the stature of Benito Pérez Galdós.

Who was the first woman member of the Royal Spanish Academy? When did she join? How many female academicians have there been in the more than three hundred years of the institution’s history? Have they all devoted themselves exclusively to literature?

There are currently several women academicians and two of them have a special relationship with Aragón: Soledad Puértolas and Aurora Egido. What do you know about them? Search the internet for information about their lives and careers.

María Moliner on the internet, on television, in the theatre and at the opera

16-03-2004.

The Aragonese filmmaker Vicky Calavia filmed a documentary entitled Tendiendo palabras.

And not only that. In 2012, a play entitled El diccionario (The Dictionary), starring María Moliner, was premiered. It was written by Manuel Calzada and published in book form a year later. And in 2016, María Moliner… an opera was premiered at the Teatro de la Zarzuela in Madrid! Focusing on the moment when she embarked on the elaboration of her dictionary, it revealed her intuitions, her passions, her nostalgia and fantasies, as well as the cruel illness which in her final years made her forget all the words she herself defined.

María Moliner and her dictionary

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by the Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: