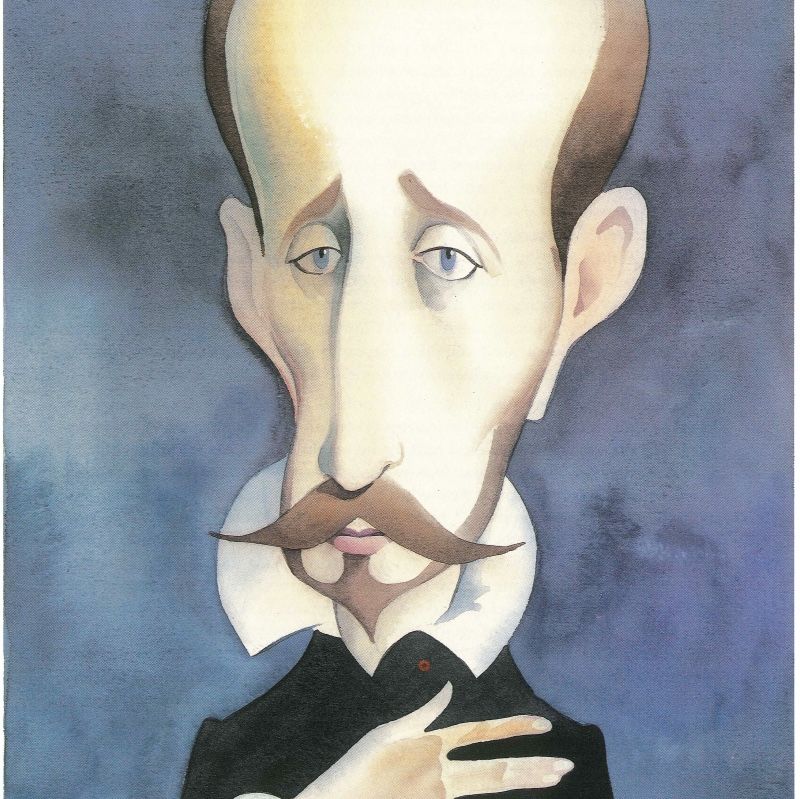

Juan de Lanuza

Short life, long posterity

Saragossa, 1564 – 1591

Juan de Lanuza V has gone down in history for his death: little has transcended a short life of twenty-seven years, but his end on a scaffold, paying the price for the simple fulfilment of his duties and the law, has transcended the centuries and has brought with it his immortalisation as a symbol of the rights and liberties of Aragon.

He has gone down in posterity with the nickname of El Joven or El Mozo, because he never went beyond that. In contrast, his father, Juan de Lanuza y Perellós, who held the office for 37 years after succeeding his brother Ferrer in 1554, is remembered as the Old Man or the Fox (alluding to a cunning that the passing of the years surely gave him and which his son lacked). Perhaps the letters of the young Justicia began to be marked by certain events at the court of the most powerful monarchy in the world.

Life

Antonio Pérez, son of Aragonese who had flourished at the Madrid court of Philip II, fell out of favour with the king. He was certainly no stranger to the intrigues and bad arts that were common in this scene of influence and rivalry, but the attribution of a murder (that of Escobedo, secretary to Juana of Austria) in an episode that could compromise the monarch himself, was a big deal and Pérez landed himself in prison. Amidst torture and facing a foreseeable guilty verdict, he escaped, crossed the kingdom’s border at Ariza and, appealing to his legal status as an Aragonese, availed himself of the right to demonstrate. This allowed him, under the guardianship of the Justice of Aragon, to be held in Saragossa, the capital of the kingdom, in a prison outside the power of the king and safe from mistreatment, while waiting for the trial to be heard with legal guarantees.

The king denounced Pérez as a heretic so that he could be taken prisoner by the Inquisition and overcome the legal obstacle that challenged his power. On 24 May 1591, violent disturbances, during which the Marquis of Almenara, the king’s representative, was mortally wounded, accompanied the coming and going of the prisoner, who was returned from the prison of the Holy Office (in the castle of the Aljafería) to the prison of the manifestados. After months of jurisdictional debates and negotiations, an attempt to transfer the prisoner on 24 September had a tragic outcome, with several dozen dead and wounded and the escape of Pérez (who, after several vicissitudes, ended up in France). The young Lanuza had just succeeded his father, who had recently died, and his hands and feet were tied: he had complied with the provisions established by the monarch but, if he continued along this path, he could not escape popular pressure and the wrath of the mutineers.

Backstop

Executed

The Justicia took refuge in Épila, together with the Count of Aranda and the Duke of Villahermosa and, a few weeks later, returned to Saragossa as if nothing had happened. Some call him unconscious; others say he was simply doing his duty. Negotiations with King Philip’s emissaries to cancel the counter-fuero and return the waters to their course failed, some allude to bad advice, wrong decisions, lack of foresight…. The fact is that the monarch, enraged, signed an order for the arrest and execution of the Justicia Juan de Lanuza V.

On 20 December 1591, with an audience made up exclusively of Castilian soldiers, the Justicia of Aragon was beheaded and then decapitated. With a clear look in front of him, he defied the accusations of “traitor, who raised a flag and other devices of war against his king and natural lord”.

References

-

We show here some of them. In addition to the strictly biographical information about Juana de Lanuza, some contextual references are provided.

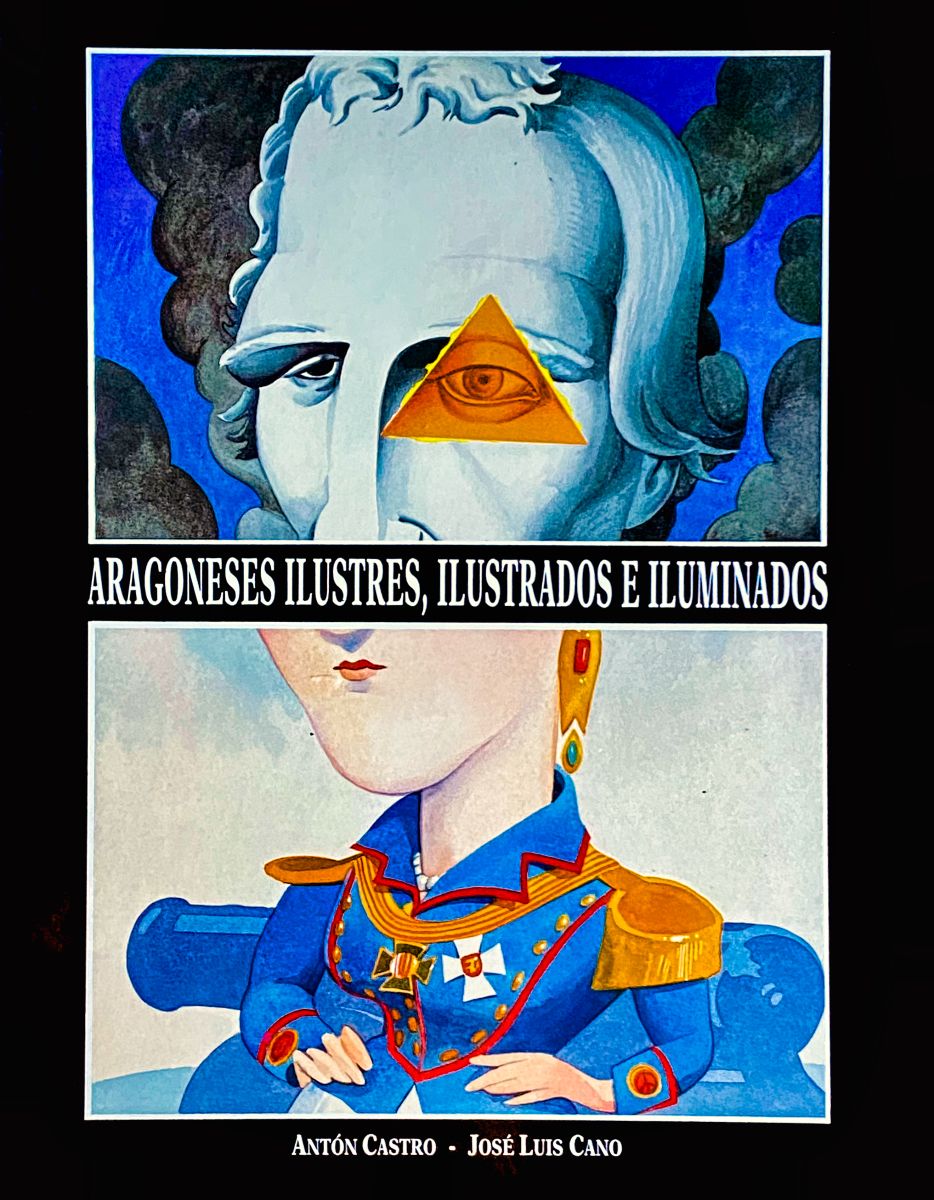

- Antón Castro (1993): “El candor y la muerte de Juan de Lanuza”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (78-83). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Jesús Gascón Pérez (2008): Aragón en la monarquía de Felipe II. Historia, pensamiento y oposición política (2 vols.). Zaragoza: Rolde de Estudios Aragoneses. Libre acceso:

- https://www.roldedeestudiosaragoneses.org/wp-content/uploads/REACCA4748AragnFelipeII.pdf(vol. 1: Historia y pensamiento)

- https://www.roldedeestudiosaragoneses.org/wp-content/uploads/REACCA49AragnFelipeII.pdf (vol 2: Oposición política)

- Encarna Jarque (1991): Juan de Lanuza, Justicia de Aragón. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_de_Lanuza_y_Urrea

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line. Monográficos de Historia: La Edad Moderna en Aragón. Siglo XVI. http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/monograficos/historia/edad_moderna_en_aragon/default.asp In particular, the themes 4 (“El autoritarismo de la monarquía”) y 5 (“La defensa de los Fueros”).

- Emilio Gastón, Guillermo Fatás y José Luis Cano (1991): El Justicia de Aragón. Zaragoza: El Justicia de Aragón. Cómic. https://eljusticiadearagon.es/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2022/01/COMIC-EL-JUSTICIA-DE-ARAG%C3%93N.pdf

- Carlos Serrano, Daniel Viñuales (2015): El Justicia de Aragón, en Ejea se hizo ley. Ejea: Ayuntamiento. Cómic. https://www.roldedeestudiosaragoneses.org/wp-content/uploads/REAsal18cmicjusticiaB.pdf

Teaching activities

The historic moment

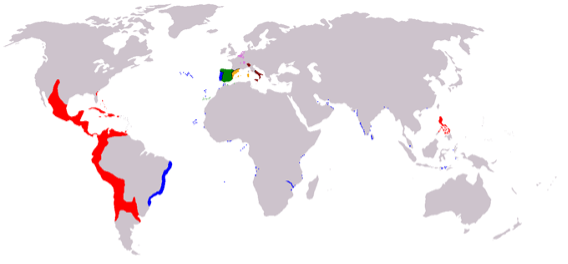

Territories attached to the Council of Castile | Council of Aragon | Council of Portugal | Council of Italy | Council of the Indies | Council of Flanders including those disputed with the United Provinces.

Changing reality

The kingdom of Aragon maintained its charters and institutions, but its role was increasingly secondary and it was very subordinate to the interests of the Empire. The trend, already outlined by the Catholic Monarchs decades earlier, was in the direction of strong, authoritarian and centralised states, which were incompatible with the peculiarities of the territories that made them up. Jealous of their political identity, the ruling classes of the kingdom had been immersed for the whole century in a dispute over powers with the monarchs, who appointed people not born in Aragon as representatives in the kingdom. This legal conflict (the lawsuit of the foreign viceroy) was indicative of a deeper malaise that extended to other layers of society. In the 16th century, production had not increased as much as the population, inequality and injustice prevailed (especially in certain seignorial domains). The rebellion of vassals against their lords (the peasant uprising in Ribagorza was very violent), banditry… were evidence of a situation of great conflict.

The episode in which Juan de Lanuza was involved was a reflection of all this unrest. It also revealed the failure of the kingdom’s institutions to adapt to a changing reality and the contradictions of a ruling class clinging to its privileges. If you read topics 4 and 5 of the Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line cited in the Bibliography, you will be able to answer these simple questions:

1. The reign of Philip II marked the last and definitive stage of the imposition of

-

- socialism crowned

- royal authoritarianism

- monarchical liberalism

- socialism crowned

2. The fueros of Aragon were a compilation of laws which

-

- limited the power of the king

- reinforced the power of the king

- limited the power of the king

3. In the lordship lands, the king’s representatives could take whatever

-

- could take whatever products they wanted

- could judge blood crimes

- were barred from exercising justice

- could take whatever products they wanted

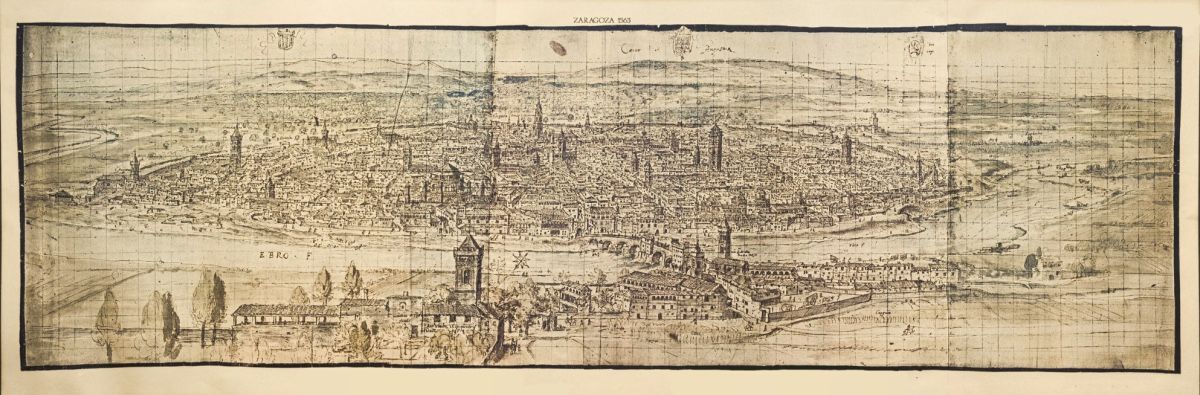

Saragossa: a paradox and many scenarios

However, in that city there were also miseries and inequalities that undoubtedly fuelled the riots and revolts of 1591.

As we have already seen, the life of Juan de Lanuza is strongly marked by a transcendental political and social event that took place in the kingdom of Aragon at the end of the 16th century: the alterations of Aragon, or the Aragonese rebellion against King Philip. An event which, as we also already know, responds to a context. Many of the events linked to this historical moment had very recognisable settings within the space of Saragossa.

On a map of Saragossa, he locates these places linked to the events of 1591:

- The Puerta de Toledo, where the prison for demonstrators was located, in the area around what is now Calle Manifestación (now you know why it is called Manifestación).

- The Plaza del Mercado, which was in the vicinity of the Central Market, where Juan de Lanuza was executed. A plaque on the wall of the Market commemorates him.

- The Aljafería Palace, where the prison of the Inquisition was located.

- The Santa Engracia gate, through which Antonio Pérez fled during the disorders of 24 September.

- In addition to these, there are two other important places of memory: the monument to the

- Justiciazgo in the Plaza de Aragón, and the church of Santa Isabel (or San Cayetano, in the Plaza del Justicia), where the remains of Lanuza are to be found.

Ideally, you should be able to see these places in situ on an excursion around Saragossa, which can be easily arranged.

The consequences

The repression of the rebellion against the king resulted in the execution of Juan de Lanuza and more than fifty other important people, as well as the imprisonment of Aranda and Villahermosa. A few months later, in 1592, Philip convened the Cortes of the kingdom in Tarazona, where the king was given carte blanche to appoint a viceroy at will and dismiss the Justicia, putting an end to the life and hereditary nature of the institution. The Diputación was also stripped of its powers over public order in favour of the Audiencia Real, the king’s officials were allowed to enter manorial lands to prosecute criminals, and measures were introduced to control the printing of books. The Cortes approved a subsidy of 700,000 Jaquesan pounds and the troops were to leave the kingdom, leaving garrisons in the Aljafería in Saragossa and the Citadel of Jaca.

The struggle between the king and the kingdom was decided in favour of the former. The functions of the institutions themselves were greatly reduced. A new era was heralded in which the monarch would take the initiative.

Search the web for information about the Cortes of Tarazona. In the wikipedia entry you can find more information about what you have just read, and also find out when the next Cortes were held. Why do you think it took so long?

The next Cortes of the kingdom were held in Barbastro in 1626, 34 years later! They were convened by Philip IV, after his father Philip III had never convened them. The kings had always been reluctant to convene Cortes because it meant having to make concessions; when they did it was usually as a means of resolving situations of extreme urgency and, above all, in order to obtain subsidies to finance military campaigns. The situation created after the events of 1591, clearly favourable to the interests of the monarchy, made this instrument of control over the king’s actions less and less necessary: the monarchy almost had carte blanche to do and undo as it pleased.

Justice, a “special” institution

Seeing it, you will be able to answer these simple questions:

- In which Cortes (place and year) was the institution of Justice regulated?

- What are the four foral processes included in the Fueros of Aragon (one of them will ring a bell, because we have mentioned it a few times)?

- Complete: From the first half of the 16th century, the Diputación del Reino appointed the ……… del Justicia.

- In what year and by what decrees was the institution of Justicia abolished?

- In which countries did the memory of the Justicia and Aragonese laws have any influence during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries?

- In what year was the first homage to the Justicia held in front of his monument in Saragossa?

Culture and memory

Another type of consequences are those that materialise in the form of homage and recognition, both of the figure of Lanuza and of the institution of Justice in general. The memory of an affront, of an attack on the liberties of the kingdom, was made to correspond with the memory of those same liberties.

In the 19th century, liberal and progressive jurists and politicians claimed Aragonese constitutionalism and the figure of Justice as its most definite contribution, and several history painters reflected the critical moments before and after Lanuza’s death. In panel 5 of the exhibition “El Justicia de Aragón, 1265-2015” you can see works by Eduardo López del Plano, Victoriano Balasanz and Mariano Barbasán.

The inauguration of the monument to the Justiciazgo, the work of Félix Navarro, in 1904, provided an emblematic place of memory for the collective Aragonese imagination. The 20th of December (anniversary of the execution of Lanuza) is instituted as the Day of the Rights and Freedoms of Aragon, and institutional and vindicatory acts are programmed during this day. In panel 8 of the aforementioned exhibition you can find out more details about this issue.

Justice of Aragon 2.0

In 1982, the Statute of Autonomy of Aragon recovered the figure of Justice, adapted to the new times, as a defender of citizens’ rights, of the Statute itself and as a guarantor of the Aragonese legal system. The third highest authority of the autonomous community after the presidents of the Government and the Cortes, he heads an institution that is highly valued by the citizens of Aragon. It is, without doubt, the most useful and effective way in which the historical figure with the tormented image of Lanuza el Mozo can cast his shadow.

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: