Fernando el Católico

Power in capital letters

Sos, 1452 – Madrigalejo, 1516

The son of Juan II of Aragon and Juana Enríquez of Castile, Ferdinand knew power as a child: he was Count of Ribagorza and Duke of Montblanc at the age of six, at the age of nine he was recognised as heir to the Aragonese throne and at sixteen he was King of Sicily. It was 1468 and Ferdinand had already spent some time as lieutenant general of a Catalonia at civil war, where he became familiar with administration and the arts of negotiation.

The following year he agreed to marry his cousin Isabella, Princess of Castile, whose dispute for the throne with Juana (daughter of her half-brother King Henry IV) was already looming and would take the form of open warfare in 1474 on the death of the Castilian monarch. The Concord of Segovia made Ferdinand king of Castile, on an equal footing with Isabella, and everything was clarified after his victory in the War of Castile (where Portugal supported the opposing cause), consolidated at Alcaçovas in 1479.

That same year, the death of his father made him king of Aragon. Here Ferdinand tied down a nobility clinging to their privileges, appointed his (unmarried) son Alfonso archbishop of Saragossa and lieutenant general of the kingdom, and seized municipal control of the capital; later, the Supreme Council of Aragon allowed him to strengthen that government while the Cortes approved generous subsidies for the king’s increasingly costly military campaigns.

Isabella and Ferdinand pursued an authoritarian and centralising policy over the territories they ruled, which differed greatly in customs, laws and institutions. The imposition of the Santa Hermandad and the corregidores, the control of Justice, the increase in the powers of the Royal Council and the scant convening of the Cortes were examples of this. The creation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a court that did not recognise borders between states was fundamental to this agenda of political and religious control.

In Aragon, the inquisitor Pedro de Arbués was assassinated in the cathedral of La Seo, and this made the situation of the Jews even worse. They had already been suffering violence and arbitrariness for decades, and the outcome was the expulsion decree of 1492. In the same year as the conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, the unity between Church and State was staged, and the discovery of the Indies laid the foundations for the global projection of the Hispanic monarchy, in which Aragon would be left behind.

Ferdinand’s relations with France were always very complicated. The Pact of Barcelona enabled him to recover Roussillon, but the conflict moved to Italy, where the French threatened Naples. There, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, the Great Captain, achieved important victories for Ferdinand, although clashes in Catalonia remained constant. Ferdinand combined successes and failures in North Africa, where he took some places as part of his policy of confrontation with the Turks, who were dominating the Mediterranean and threatening central Europe. With the excuse of supporting the Papacy in its conflicts with France, he invaded Navarre (a traditional ally of the French) and imposed a Castilian viceroy.

Regent of Castile after Isabella’s death in 1504, he rivalled his son-in-law Philip of Austria, to whom a large part of the Castilian nobility, who were at odds with Ferdinand, were close. To undermine his rival’s position, he married the very young Germana de Foix, niece of the King of France. The death of his son Juana shortly after his birth aborted the possibility of a line of succession on the Aragonese side, outside Castile.

Frustrated in his attempt to renew his descendants, old and battered… his heart failed him on his way to the monastery of Guadalupe. He asked to be buried in Granada. His son, the aforementioned Alfonso, Don Alonso, was regent of Aragon (as Cardinal Cisneros was of Castile) until the arrival from Flanders of Ferdinand’s grandson, Charles. Juana and Philip’s son was to continue the legacy that was to usher in a new era.

References

-

There is an immense bibliography on Ferdinand the Catholic. Protagonist of an era, with enormous influence on posterity… his life, his time and his legacy have been the subject of a multitude of publications. Here are just a few of them:

- José Ángel Sesma (1991): “Fernando el Católico”. En VV. AA., Historia de Aragón (pp. 265-288). Zaragoza: Heraldo de Aragón.

- John Edwards (2001): La España de los Reyes Católicos, 1474-1520. Barcelona: Crítica.

- José Luis Cano (2005): Fernando el Católico. Zaragoza: Xordica.

- Salvador Rus (2015): Una biografía política de Fernando El Católico: La constitución de una monarquía universal. Madrid: Tecnos.

- Aurora Egido, José Enrique Laplana (coord., 2014): La imagen de Fernando el Católico en la Historia, la Literatura y el Arte. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico.

- Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_II_de_Arag%C3%B3n

- “Fernando II y Aragón”, dentro del monográfico La Corona de Aragón II: Los Trastámara (Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line): http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/monograficos/historia/corona_de_aragon2/fernando_aragon.asp

Ferdinand II of Aragon has been the focus of studies, conferences, exhibitions… During 2016, the V Centenary of his death brought together a large number of activities. The Institución Fernando el Católico (Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza) dedicated to the Aragonese king a lot of publications, summarised in this link: https://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/34/90/_ebook.pdf

The series Isabel, broadcast by Televisión Española for three seasons between 2012 and 2014, was a great success. Apart from its technical and artistic merits, there was no shortage of criticism of the view of Ferdinand. The Aragonese was presented as the main person responsible for decisions that are more difficult to understand in today’s eyes (the establishment of the Inquisition, the expulsion of the Jews…). He provided an unkind (sometimes cruel and selfish) counterpoint to the also firm and ambitious (but sweetened) Isabella. Evidently, she was the protagonist of the series.

The complete series is freely available on the RTVE platform: https://www.rtve.es/television/isabel-la-catolica/capitulos-completos/

Isabel had a sequel in the form of a film, La corona partida, set in the power struggles after the death of the Queen of Castile.

Teaching activities

The cradle of a king. A visit to Sos del Rey Católico

Sos del Rey Católico is well worth a visit. Both the town itself and the surrounding area have a magnificent historical, artistic and natural heritage. Plan an agenda for a possible excursion to Sos del Rey Católico: points of major interest, stops or small detours that are worth making on the route from your place of residence, etc.

A “very Aragonese” king, or not so much?

During his intense life, Ferdinand was, in this order, King of Sicily, Castile, Aragon, Sardinia, Naples and Navarre. With him, the Crown of Aragon (which contained several states, including the Kingdom of Aragon) played an important role in the international politics of the time. This king is considered one of the architects of the construction of Spain and Europe, fundamental in the transition from the Middle Ages to Modernity. In all this, his status as an Aragonese is very much blurred.

Grandson of the Trastámara elected king at Caspe (in homage to whom Ferdinand was baptised), seven of his eight grandparents were Castilian and he was born in Aragon by the skin of his teeth: his mother was in Navarre, accompanying her husband in the war that the Aragonese king was waging with his first-born Carlos de Viana. Aware of the importance of her son being born in Aragonese territory to strengthen her position, Queen Juana gave birth in the Sada manor house in the border town of Sos. Of his 37 years as ruler of Aragon, Ferdinand spent barely three in the kingdom. The affairs of Castile, Granada and Italy kept him much more preoccupied than the vicissitudes of the small state within whose borders he had been born.

We must put ourselves in context. Ferdinand the Catholic was Aragonese, to be sure, but his politics, strategies and interests led in other directions. The logic underpinning the actions of the powerful during the Middle and Modern Ages was not “patriotic” and had nothing to do with “national” sentiment. The states governed by the Catholic Monarchs were family “possessions”, patrimony resulting from inheritance or conquest, in the management of which they had to compete with local lords. Even if they could favour policies that improved the quality of life of their subjects, the kings were not public servants but landowners. Ferdinand had Aragon as one of his possessions (perhaps his most prized?), which he took care to keep under control.

What mechanisms did Ferdinand employ to maintain this control over the kingdom of Aragon? The biography says something about this, but you can look in other sources for more information about the Supreme Council of Aragon, or the occasions on which Cortes of Aragon were held during the reign of Ferdinand II.

A wedding with a twist and an adventure

The marriage of Isabella and Ferdinand was a marriage of political convenience, although there was also a great deal of personal rapport (some would call it “love”). Both had the surname of Trastámara and were second cousins. For their marriage to be recognised, they needed a papal dispensation, which Pope Paul III refused to grant. The solution: a false bull fabricated by Alfonso Carrillo, the archbishop of Toledo. When the pope found out about the trick, he excommunicated the forgers. The marriage would be recognised two years later by the new Pope Sixtus IV, advised by the Valencian Rodrigo Borgia (the future Pope Alexander VI).

The wedding took place in Valladolid and Ferdinand took an enormous risk on the journey from Aragon. The enemies of Isabella’s candidacy for the throne of Castile were watching the border, and were even prepared to kill him. He made the journey disguised as a groom to throw them off the scent.

Why was there opposition to the marriage between Isabella and Ferdinand? What were the interests behind it? Who was it prejudicial to? Look for information about it.

Marriage policy, reasons of State… and another woman left behind: Juana of Aragón

The marriage of Isabella and Ferdinand had been the result of a strategy of Juana II against rival France. And the kings themselves embarked their children on a marriage policy aimed, among other things, at isolating the kingdom beyond the Pyrenees. The first-born Isabella was married to Prince Alfonso of Portugal and, when she was widowed, to his brother, King Manuel, who, on Isabella’s death (in Saragossa), married another daughter of the Catholics, Maria. John was destined to reign and was married to Margaret of Austria, daughter of Emperor Maximilian, whose son Philip was to marry Juana, the third. But John died before his twentieth birthday and the burden of succession would fall to Juana and Philip. To England was sent the younger Catherine who, after the death of her husband Prince Arthur, was married to her brother-in-law Henry VIII, became the mother of Mary Tudor and was involved in the English king’s break with the Church of Rome. Sound like a soap opera? Here is an outline to help you understand it a little better.

In this map you can see the extent of this strategy. Where do you think the will of the children was in all this? It can be a good element of debate.

Find a map that shows the inheritance of Carlos, grandson of the Catholic Monarchs and the Emperor of Germany. What consequences did this have in the following centuries?

The only other woman besides Petronila who was a fully-fledged queen of Aragon was Juana, the second daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand, heiress after the death of her brothers Isabella and Juan and nominal queen of Aragon since the death of her father in 1516. She has gone down in history as a “madwoman”, when her reality was that of a cultured, sensitive woman, a victim of the intrigues and manoeuvres of her father, her husband and, later, her own son.

Disqualified by her father in 1507, after being widowed by Felipe de Borgoña (an intriguer who has passed to posterity as “the Fair”), she was confined for almost 50 years in a palace in Tordesillas until her death in 1555. She may have had the traits of an unstable and very energetic character, but these were deliberately exaggerated to remove her from the struggles for the lords of Castile and Aragon. Her extravagant behaviour, if any, may also have been a strategy to gain a foothold in a man’s world (in which, incidentally, a strong and energetic character is considered a virtue).

Representations of power

Three very specific places in the city of Saragossa offer us very clear images of the authority of Ferdinand II of Aragon. Of course, all three can be visited, and we invite you to do so.

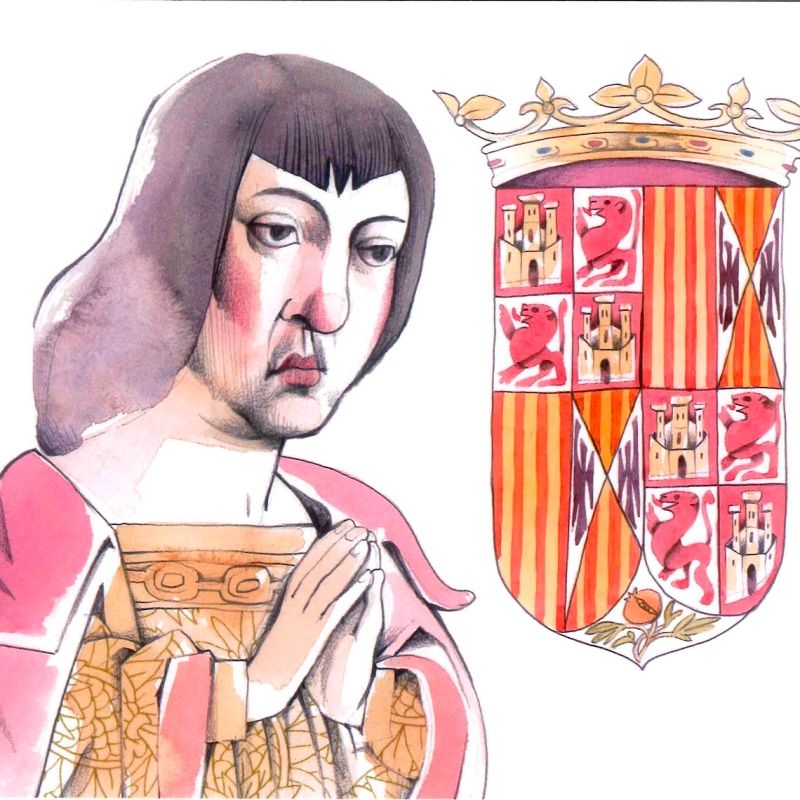

[1] The Aljafería Palace is, as we know, one of the jewels of Muslim architecture on the Iberian Peninsula. However, there are rooms inside that are the result of extensions, such as the one ordered by Isabella and Ferdinand. The Throne Room is the greatest exponent of this. Here you can see the king’s coat of arms, whose quarters represent Aragon, Sicily, León and Castile, crowned by the crest of the dragon, which represents royal dignity.

In the entry on Ferdinand II in Wikipedia you can see the evolution of his coat of arms, as different territories were incorporated. List them and locate them on a map.

There are also other emblems: the yoke and arrows, which represent the initials Y (for Ysabel in its original transcription) and F (for Ferdinand), also alluding to values such as the strength of the union, resistance and unbreakability. We can also see some loose strings, cut, alluding to the “Gordian knot”.

Find out about the origin and meaning of the Gordian knot and which important figure from Antiquity it is related to.

The legend of the Gordian knot, transposed to the time of the Catholic Monarchs, extols determination, efficiency and problem-solving without shortcuts and without contemplation. The words “Tanto monta” (“lo mismo da [cortar que desatar]”) sum up this spirit, which is not alien to negotiation either, as long as the objective is clear.

An example of an expeditious decision with this “justiciary” touch is the sentence of Guadalupe, by means of which the king neutralised the peasant revolts of the remences in Catalonia against the lords, suppressing the bad customs and executing a few wayward people.

Look up information about the thinker and diplomat Niccolo Machiavelli (Florence, 1469-1527), what is his main work, why do you think he regards Ferdinand as a model, why does he praise him? It is curious, too, to draw attention to the negative connotation that the term “Machiavellian” has today.

Machiavelli shared Ferdinand’s poor relationship with France, and considered the king of Aragon to be the model ruler that a divided and warring Italy needed. He therefore praised him, and it is possible to understand that from there he regarded him as a model Renaissance prince.

“The end justifies the means” could be the message that takes to the extreme this pragmatic and utilitarian character in the exercise of power. Ferdinand showed signs of this throughout his life. With Isabella of Castile in an unbreakable partnership (despite occasional differences), he represented authoritarianism as an expression of modernity (which other European rulers would also assume), overcoming medieval feudalism. The “centralist” attempts would follow a path that would have its maximum expression in the absolutism of the 18th century.

Over time, the “tanto monta” was joined by “monta tanto”, forming a verse to which was added, in a couplet, “Isabel as Fernando”. This phrase dates from well after the time of the Catholic Monarchs, and made its fortune, more than for extolling parity between the sexes (which in itself would be praiseworthy today), for placing the two statesmen on an equal footing. In reality, they did not rule the same, for while Ferdinand was king of Castile, Isabella was never king of Aragon. Nevertheless, this “egalitarian” discourse sought to extol the dynastic union as a Spanish “national” union, as if it had been part of a pre-established plan, with a higher purpose. This was never really the case: nevertheless, this message spread in the 19th century and was used to the full during Franco’s dictatorship (1936-1975), in which politics and religion combined to exert a great deal of social control.

[2] The statue of Fernando the Catholic in the Plaza de San Francisco in Zaragoza is not where it is by chance.

The statue is located in the area where the expansion of Saragossa towards the southwest began. The enormous growth of Saragossa during the 1960s was channelled, in part, through the provision of new extensions, wide roads in the suburbs, such as the one that, linking with the districts of Universidad, Romareda and Casablanca, connected the city centre with the exit towards Teruel. These avenues were (and are) Fernando el Católico and Isabel la Católica (joined at the Plaza del Emperador Carlos), which also lead to a belt around the western part of the city: the Vía de la Hispanidad. These names are very significant because of the connotations of the whole complex in the Spanish nationalist imaginary. It is an example of the use of history as a legitimisation of power, the projection of the past to justify the present and its use in public space.

“Saragossa to its great king”, reads the inscription at the foot of the monument. It refers to the city of Saragossa, but could also be extended to the province. Ferdinand was born within the boundaries of the province (although the province as such has existed since the 19th century), and it is no coincidence that he gives his name to the main provincial cultural institution. Look up information about the Fernando el Católico Institution: when it began its activity, what lines of work it has developed and maintains, the county centres it hosts, etcetera.

[3] The church of Santa Engracia. Its beautiful Plateresque façade (the work of the Gil Morlanes family, father and son) has something very unusual: the representation on it of people from outside the saints’ calendar and the biblical world. Contemporary” people who financed the work and wanted it to be very clear: Isabella and Ferdinand. It is a good example of an instrument of political propaganda for the monarchy.

Speaking of patronages related to King Ferdinand, it is obligatory to mention Don Alonso of Aragon. Son of Ferdinand and the Catalan noblewoman Aldonza Ruiz de Ivorra, Alonso (or Alfonso) was appointed archbishop of Saragossa in 1480, at the age of ten, in what was an obvious manoeuvre by his father to control the kingdom. In fact, his actions are more linked to politics and the military than to religion. His activities as a patron of the arts were noteworthy: a major reform of the Seo of Saragossa bears his stamp.

The first census

Among the few occasions on which King Ferdinand convened the Cortes, those of Tarazona in 1495 are of particular significance: they ordered the first fogaje, or counting of fires, in the kingdom of Aragon (there had been one at the beginning of the century, ordered by the Cortes of Maella, but it was partial). The purpose was fiscal: to keep the population under control so that no one would escape from their obligations to the Treasury (specifically the payment of the “sisas”).

Look up information on the “sisas”: what products and activities were affected by this tax?

According to this census, the kingdom of Aragon had 51,450 homes, which, at an average of 4.5 inhabitants per household, gives around 230,000 inhabitants. The city of Saragossa must have had around 18,000 inhabitants, followed by Calatayud (4,500).

Look at the comparison of that first census with the current data.

| 1495 | 2021 | |

| Aragón | 230.000 | 1.329.391 |

| Saragossa | 18.000 | 701.102 |

| Percentage of Saragossa in relation to the total for Aragón | 7,83 % | 52,74 % |

Figures for 2021 are from the Aragonese Institute of Statistics (Aragon) and the Municipal Register (Saragossa).

What do these figures suggest to you? By how much has the population of Aragon multiplied? By how much has the population of the city of Saragossa multiplied? Try doing the same operation with “Aragon without the city of Saragossa”. Many things have happened in so many centuries: industrialisation, emigration, the concentration of economic activities, the loss of weight of rural areas… Look for data that give an idea of this evolution in intermediate periods. Are the percentages more or less the same? Do the imbalances accelerate at any specific moment? Reflect on these phenomena in class.

A last impression

At the end of the 15th century, during the reign of Ferdinand II, the invention of the printing press in Germany brought about a cultural revolution of the first order. The faster flow in the transmission of knowledge and exchange of ideas brought with it many other social changes and changes in mentalities. Aragon played an important role in this process.

It is a good way, through beauty and culture, to bid farewell to this era, marked by the life of the Aragonese who most consciously and decisively directed the reins of power in history.

Fernando el Católico

Download from this link the PDF of the publication edited by Xordica publishing house with the sponsorship of the Obra Social de Ibercaja.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: