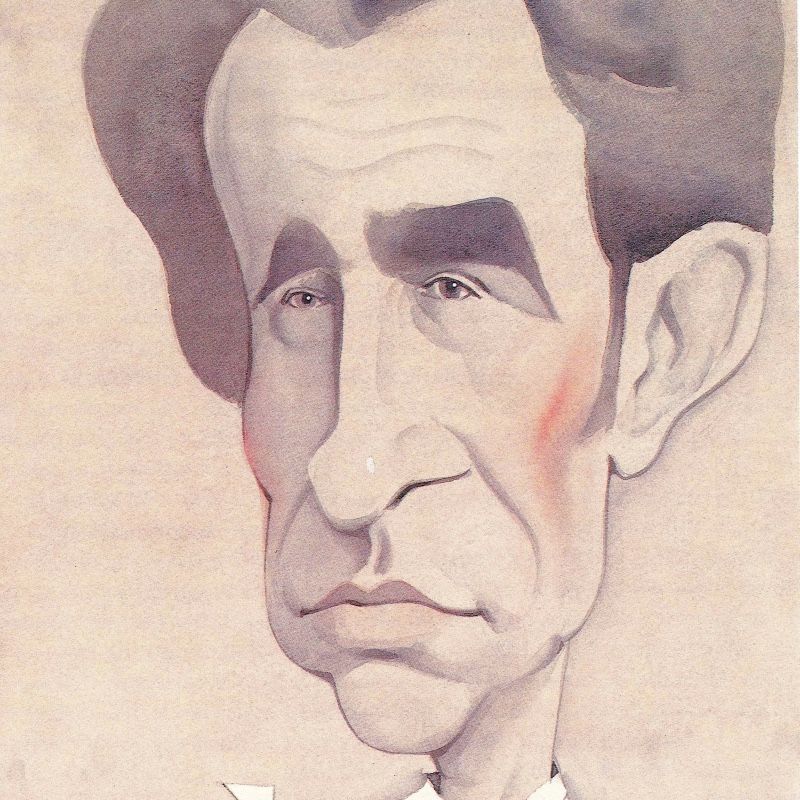

Ramón Acín

Consistency, boldness and kindness

Huesca, 1888 – 1936

Ramón Acín was born in a manor house in Huesca, known as the Casa de la Ena, which, after a more nomadic youth, he would share with his wife Conchita and his daughters Katia and Sol until the end of his life.

The youngest of the four children of María Aquilué and Santos Acín (a non-practising teacher and a surveyor), he showed an interest and talent for drawing from an early age. With the painter Félix Lafuente he acquired fluency and learned to paint still lifes and landscapes while he was still at school. He began a degree in Chemical Sciences in Saragossa, which he abandoned to go to Madrid to take the unsuccessful competitive examinations to become a draughtsman for Public Works and to experience a bit of bohemian life. Back in Huesca, he resumed classes, this time with Anselmo Gascón de Gotor, and began to publish illustrations in the press.

Life

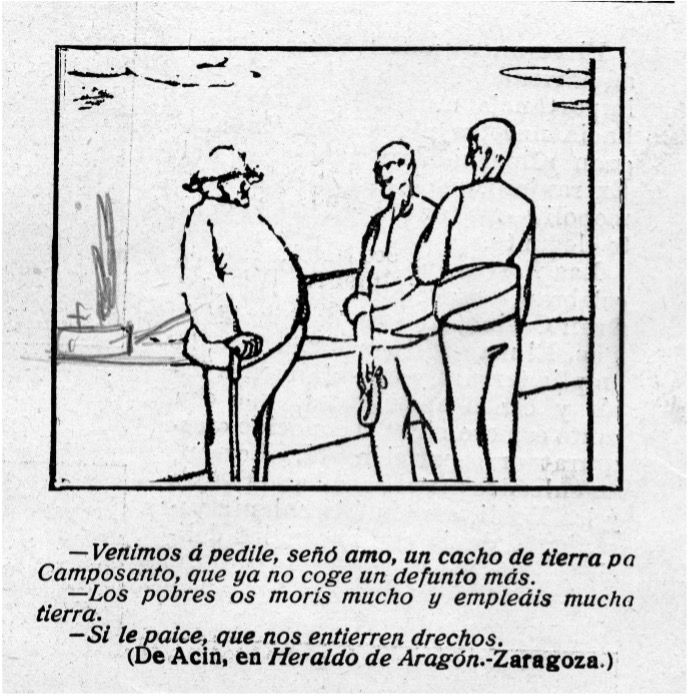

The programme for the San Lorenzo festivities in 1911 opened the doors of the Diario de Huesca, directed by Luis López Allué. There he collaborated with critical cartoons on current affairs under the pseudonym of Fray Acín. A draughtsman with simple, effective strokes, familiar with the modernism of Ramón Casas, he did not shun costumbrist prints or caricature (in the manner of Castelao or Bagaría), depicting stylised, expressive figures with incisive, sharp texts. He shared gatherings with the writer Manuel Bescós Silvio Kossti, became fond of photography and accompanied the documentary maker Ricardo Compairé on his travels in the Alto Aragon region.

He was also attracted by writing, by a journalism of political denunciation and social vindication that he put into practice in Barcelona with his friend, Ángel Samblancat from Graus, through a newspaper: La Ira (“Organ of expression of the disgust and anger of the people”) did not exceed two issues due to the problems that its inflammatory content caused with the authorities. It was 1913 and at the end of that year the Diputación de Huesca granted him a pension to further his artistic studies, which he carried out for two years in Madrid, Toledo and Granada. On his return, he took up an interim post as a drawing teacher at the Escuela Normal de Maestros y Maestras in Huesca, which became his permanent position after passing the competitive examinations in 1917.

Work

In those years he consolidated a radicalism that he had already espoused in the weekly Talión, conceived with friends such as the aforementioned Samblancat, Felipe Alaiz, Gil Bel and Joaquín Maurín. Anticaciquism, a left-wing reading of his always admired Joaquín Costa and anarchism converge in his ideological universe. Together with some of his former colleagues in Talión, he also collaborated in the Saragossa republican newspaper Ideal de Aragón.

At that time he founded the magazine Floreal, collaborated in the trade union press, wrote the Manifesto de los Jóvenes Oscenses, and formed the Agrupación Libre de Huesca Nueva Bohemia. His students at the Normal School, such as Paco Ponzán and Evaristo Viñuales, also moved along these lines. In 1919 he attended the Congress of the National Confederation of Labour held in Madrid as a delegate from Alto Aragón and took part in propaganda campaigns and trade union organisation with Maurín and Andreu Nin.

Reprisals

His political activity did not divert him from his commitment to teaching, which he saw as a fundamental part of the training of citizens. He opened a private drawing academy in his house in Huesca and continued to explore different facets of creativity, such as sculpture, where he began to work on clay modelling, bronze castings, etc. In 1923 he publishes a futurist satire: Las corridas de toros in 1970.

Married to Conchita Monrás, he had two daughters: Katia and Sol. His significance within anarcho-syndicalism led him to prison for crimes of opinion (the first time in 1924, in the midst of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship). In spite of this, as an increasingly recognised artist, he received institutional commissions: for the Huesca City Council he created the monument to Lucas Mallada in 1925 and, a few years later, the sculpture of the Fuente de las Pajaritas in the Park. He took part in the First Exhibition of Aragonese Humorists (Saragossa, 1926) and in the Goya Centenary Committee. He was in contact with the artistic avant-garde, with Luis Buñuel (with whom he met in Paris), with Ramón Gómez de la Serna… in December 1929 he exhibited his work at the prestigious Dalmau gallery in Barcelona, and months later at the Rincón de Goya in Saragossa.

Acín was one of those involved in the Republican uprising in Jaca in December 1930. His failure led him to go into exile in France, from where he returned after the proclamation of the Republic, regaining his professorship at the Normal de Huesca. The jackpot of the 1932 Christmas lottery fell in Huesca and Ramón Acín, who was one of the lucky ones, used the prize money to finance Luis Buñuel’s film Las Hurdes: tierra sin pan (The Hurdes: land without bread).

The real Republic was distancing itself from the dream Republic. Ramón Acín, an active CNT militant, was imprisoned more than once during those years (more for suspicions than for actions). He remained committed to pedagogical renewal, taking part in 1935 in the Congress on the Technique of Printing in Schools held in his city.

On 18 July 1936, Huesca fell into the hands of the rebels. Ramón’s political significance made him easy prey. He hid at home but the mistreatment and threats against Conchita led him to give himself up. On the same day, 6 August, he was shot at the walls of the Huesca cemetery. His death certificate states that he died “in a scuffle during the Civil War”. Conchita would fall shortly afterwards, on the fateful day of 23rd August, on which a hundred republicans from Huesca were murdered.

The murderers’ viciousness knew no bounds: the Tribunal of Political Responsibilities condemned and fined Ramón and Conchita after their deaths, even locating and seizing a bank account in her name. The orphaned girls, Katia and Sol, were taken in by their uncle Santos, Ramón’s brother. They studied, taught and had children. Sol wrote poems and Katia was a painter. Both maintained the essence of the Casa de la Ena.

References

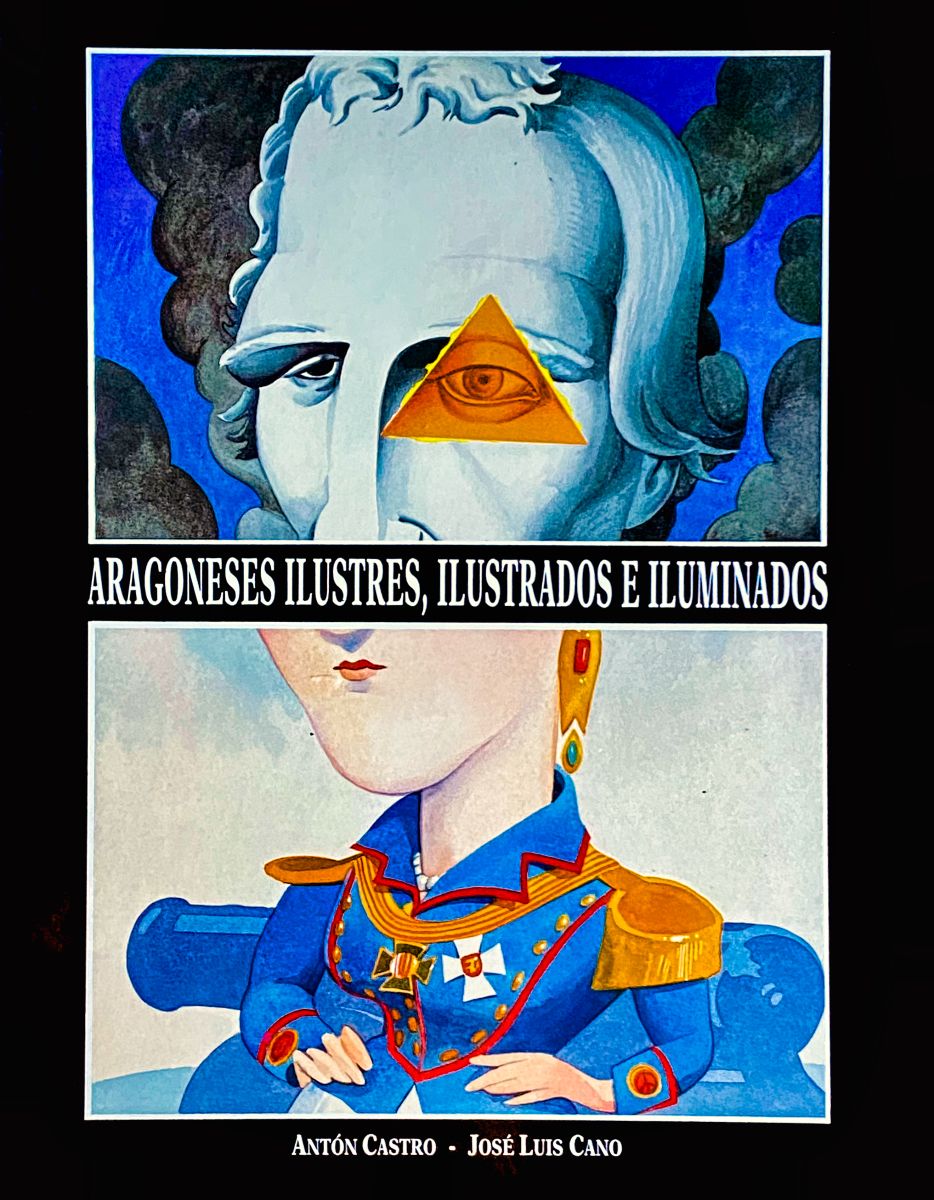

- Antón Castro (1993): “Ramón Acín, apología de la libertad”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (180-185). Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- AA. (2003): Ramón Acín. Catálogo de exposición. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.

- Víctor Juan (2020): Ramón Acín. In any of us a piece of you. Huesca: Government of Aragon – Acín Foundation.

- Spanish Biographical Dictionary, Real Academia de Historia: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/31605/ramon-acin-aquilue

- Website of the Ramón and Katia Acín Foundation: https://fundacionacin.org/

- Chalk in his pockets. Ramón Acín, the incorrigible good name. Documentary directed by Emilio Casanova (2019). Trailer: https://vimeo.com/319209908

Teaching activities

The Huesca of Ramón Acín

In the text we have mentioned people who were well known in the culture and society of Huesca and Alto Aragón in the first decades of the 20th century. Somewhat older than Ramón Acín, he learned from all of them and was friends with all of them.

Relate them with their appropriate descriptions.

- Félix Lafuente

- Luis López Allué

- Manuel Bescós

- Ricardo Compairé

- a) Writer of local customs, director of the Diario de Huesca, lawyer

- b) Painter, well known author of Huesca landscapes.

- c) Photographer and documentarian of villages, landscapes and people of Alto Aragon.

- d) Trader and lawyer, real name of writer Silvio Kossti

Solutions: 1-b; 2-a; 3-d; 4-c

Look for these emblematic places in Acín’s life on the map of Huesca:

Casa de la Ena – Fuente de las Pajaritas – Facultad de Educación (where he taught) – Museo de Huesca (where there are works of his).

You can look for some more, if you like, and design a “Ramón Acín route” in the city, with an itinerary that could end at the Pedagogical Museum of Aragon.

The renovator of pedagogy

Ramón Acín believed in new ideas for a new, freer, more cultured and fairer world, based on a profound humanism. This was the basis of the hard work of pedagogical renewal that he undertook. He wanted a school that would banish “the letter enters with blood” and make room for equality and natural goodness.

He approached learning as discovery and play, based on experimentation, imagination and collaboration. He inherited the postulates of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza and of his admired Joaquín Costa, adding to them more advanced ideas of self-management, of autonomous but supportive decisions.

His extensive pedagogical work was not confined to schools. He believed that society would be freer with more culture and with means of survival that would humanise the lives of the working class. As the Acín Foundation points out, “he did not write treatises or give canonical instructions on the subject. He built a coherent life and practice in all areas. The personal, the pedagogical and the artistic intermingled in his actions, in his works, in his excellent journalistic writings and in his intense anarcho-syndicalist work”.

Select: Exhibitions / Permanent Exhibition. Choose one of its short chapters: can you summarise the main ideas, is anyone named in particular, is there anything that stands out to you, that is relevant to the present day? Share this work in class and discuss it together.

It can be a good preparation for visiting the Pedagogical Museum and getting to know Ramón Acín’s Huesca better.

The agitator, the activist

From his youth, Ramón Acín was close to friends with whom he shared social and political attitudes. All of them were admirers of Joaquín Costa and defended an increasingly radical left-wing republicanism, which led them to come closer, to varying degrees, to Marxism and anarchism. Some became political leaders, others had some success as writers and edited newspapers. All of them will survive the Civil War, but in unenviable conditions (one will be saved from the wall by a miracle, others will die in exile in Paris, Mexico and New York).

He does a little research on the young Acín’s revolutionary companions and relates each of them to their place of birth and to an important element of their biography.

A) Ángel Samblancat 1.- Utebo a) Marxist Unification Workers’ Party

B) Felipe Alaiz 2.- Bonansa b) Director of Land and Freedom and Workers’ Solidarity

C) Gil Bel 3.- Belver de Cinca c) President of the Barcelona Court of Appeal during the Civil War.

D) Joaquín Maurín 4.- Graus d) Novel Down with the bourgeois

Solutions: A-4-c; B-3-b; C-1-d; D-2-a

Ramón Acín had to go into exile after the failure of the Republican uprising in Jaca. Who was this uprising against? Who had previously governed Spain between 1923 and 1929? Who was behind this uprising? What were its immediate consequences? And in the medium term, was the monarchy saved?

Define these concepts: “Marxism”, “anarchism”, “anarcho-syndicalism”. What does the acronym CNT stand for and what ideology does it hold?

Leader of the Huesca CNT, Acín is an anarchist who hates violence (including violence against those who think like him); he is an atheist who questions the abusive power of the Church, but does not criticise the faith of believers and respects their spirituality. His humanism places reason and understanding between different people at the top of his list. He hates sectarianism. Perhaps all this made him more dangerous for the enemies of democracy and the Republic: “the intolerant knew that in pedagogy, in freedom of thought and action, lay their enemy. That is why he was one of the first people killed in Huesca after the fascist uprising of 1936. That is why so many teachers and free intellectuals died. The death of intelligence facilitates slavery”.

As a writer and journalist, Ramón Acín exhibits very personal and direct opinions, without half-measures. His social and political criticism is already very marked in his first known text.

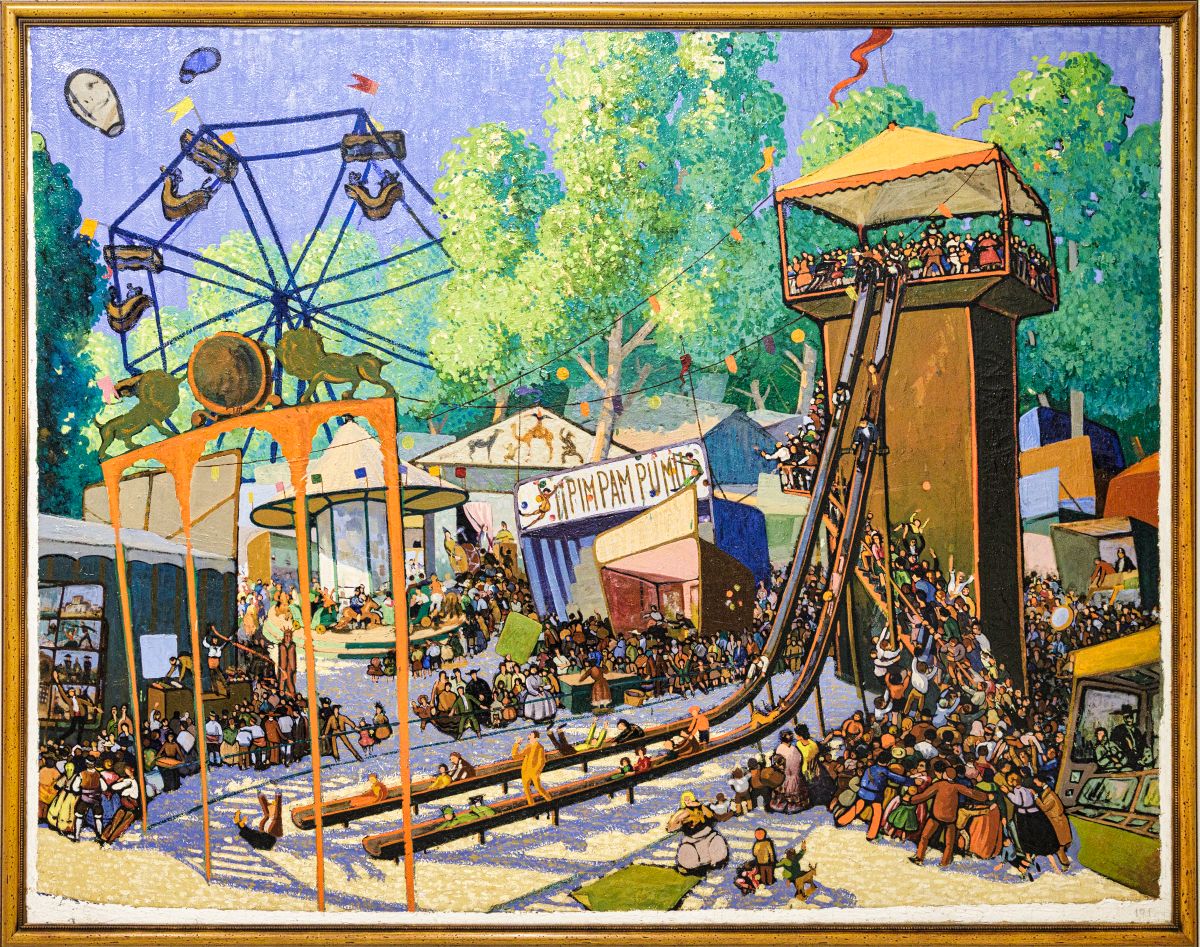

The artist

Ramón Acín translated his aesthetic ideas and his way of seeing the world into artistic expression. Endowed with a broad culture, he assimilated the new concepts of the avant-garde in a very personal way. He defies convention and does not renounce the multiple facets and forms of art conceived as manual work: bold typographies, posters, drawing, collage, metal sheet pieces, modelling, fusing, etc. He reveres his masters, respects them, and is a man of art. He reveres his masters, respects the classics, but is not silent in the face of those who are short-sighted. For example, he defended the much criticised rationalist architecture undertaken by Fernando García Mercadal in the Rincón de Goya, in a very strong plea in defence of the new arts.

Visit the website of the Acín Foundation. Choose a work from each of these links:

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: