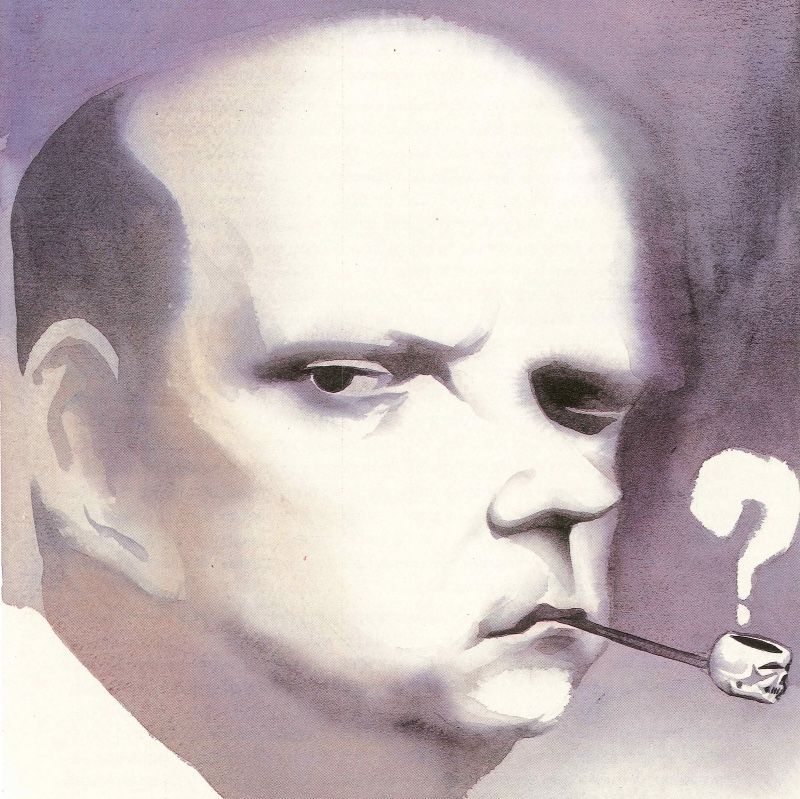

Miguel Labordeta

Wanted… world citizen poet

Saragossa, 1921 – 1969

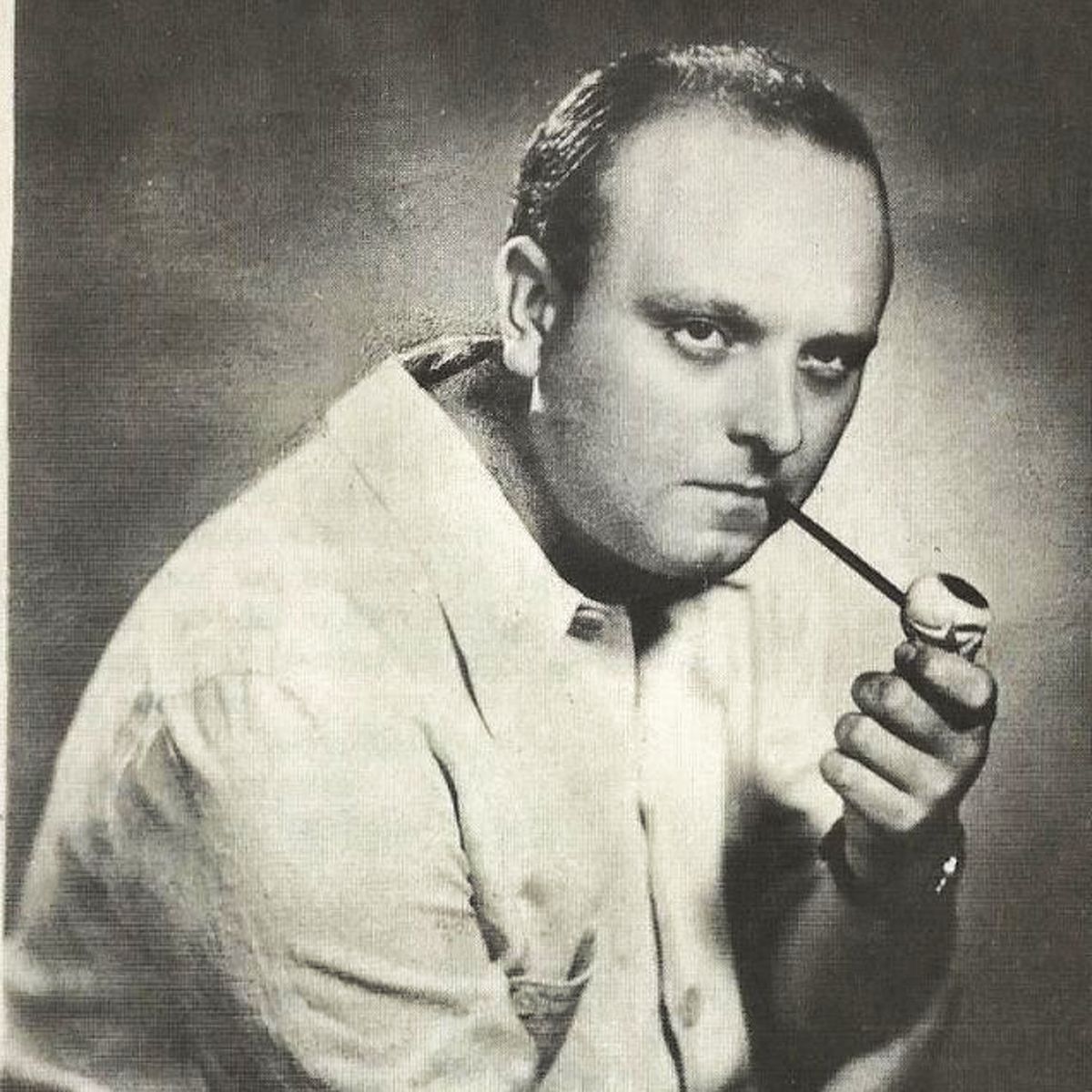

The best Aragonese poet of the 20th century lived his early years in a Saragossa in transformation. In addition to his holidays in the lands of Belchite, where his mother, Sara Subías, had her roots, Miguel’s childhood had its microcosm in the neighbourhoods near the Central Market. In this environment, in the Calle del Buen Pastor, was the Gabarda family house, which housed the family home and the Santo Tomás de Aquino school, run by his father, Miguel Labordeta, a Latin teacher, Catholic, liberal and republican.

That world was savagely cut short by the outbreak of the Civil War. Fear settled in the house, with the threat of arrest hanging over the father and with wounded soldiers, refugees, relatives… passing through. The war ended, but peace never came. The young Labordeta, the eldest of five siblings, studied Philosophy and Arts and went to Madrid to do his doctorate. Although he would abandon his academic career, in the Spanish capital he attended gatherings, made contact with writers and absorbed a multitude of influences which he would make his own.

Life

In 1947 he returned to Saragossa. “I threw up in the Saragossa wormhole”, he later recalled. He was called up, posted to Jaca and later to his home city. Here he began to work as a History and English teacher at Santo Tomás and in 1948 he published his first book of poetry: Sumido 25. The volume opened with a poem entitled “Espejo” (Mirror) and with the line: “Dime, Miguel, ¿quién eres tú? There, in the words of Antón Castro, “he began the existentialist adventure of the quest for the self with a flowing language that partook of surrealist disorder and excess. He possessed a powerful imagination, depth and trembling”.

It was not an easy or popular poetry: Labordeta approached the avant-garde from baroque and romantic roots in his new collections of poems Violento idílico and Transeúnte central. This poetic cycle came to an end in 1951 with Epilírica, which could not be published until 1961 due to problems with the censors.

Work

A lot had happened in those ten years. On the death of his father in 1953, he had taken over the management of the family school together with his brother Manuel. Although he did not feel a special pedagogical vocation, he felt called to continue Don Miguel’s work, promoting initiatives such as the school magazine Samprasarana, but he was too absorbed by bureaucracy. Perhaps he lacked a left hand when dealing with the authorities, who made it difficult for him to manage the school, which was drowning in debt.

Shy with women, unresponsive in love with a young woman idealised under the name of Berlingtonia, Miguel Labordeta was a man who shied away from social relations, not very fond of posturing and somewhat surly, but tender and affectionate. Despite being in contact (mainly through letters) with great writers and artists, from the sculptor Pablo Serrano (author of a bust of the poet) to the playwright Francisco Nieva and the poets Vicente Aleixandre, Gabriel Celaya, Ignacio Aldecoa and Jorge Guillén, among many others… he felt isolated and unrecognised. The failure of his play Oficina de Horizonte contributed to this: it premiered at the end of 1955 in a matinee session at the Argensola. With stage design by the Basque artist Agustín Ibarrola and a surrealist backdrop, it was ignored by the official culture and the possibilities of promotion and representation were very limited.

Café Niké

The poet projected much of his sociability in a more purely creative environment, by promoting an important literary gathering at the Café Niké. Dozens of cultural figures frequented this centrally located café in Saragossa over the years. Julio Antonio Gómez, Raimundo Salas and Guillermo Gúdel accompanied him in the early days of the gathering, which was to be joined by young (and not so young) poets such as Manuel Pinillos, Luciano Gracia, Emilio Gastón, Ignacio Ciordia, Rosendo Tello, Fernando Ferreró, Raimundo Salas, Benedicto Lorenzo de Blancas, José Antonio Rey del Corral, Vicente Cazcarra, José Antonio Labordeta. … playwrights such as Eduardo Valdivia, painters such as José Orús, film people such as Manuel Rotellar, Emilio Alfaro, José Luis Pomarón and Antonio Artero, and so on.

It was there that Miguel set up his International Poetry Office, from which he launched manifestos and issued his world citizen’s cards. Imaginative proposals, jokes and irony were on the menu at the Niké. The members of the OPI were to launch many initiatives: the magazines Despacho Literario, Papageno and Orejudín, several publishing houses (Coso Aragonés del Ingenio, Javalambre) and literary collections (Poemas, Fuendetodos) from which dozens of books of poetry, essays, narrative, theatre, criticism… were published.

Miguel Labordeta would have liked to write more. He did so in magazines (his anthology Memorándum was published in 1959 as number 5 of Orejudín), he was able to publish his delayed Epilírica in 1961, and a new anthology, Punto y aparte, would see the light of day in 1967, but he did not write as much as he would have liked. She was bitter about having to invest so much effort in keeping the school alive. She combined her love of travelling with voluntary and prolonged confinement to her room to read: her extensive library included history, biography, yoga, spiritualism and psychoanalysis; she was passionate about oriental literature, she read French poetry and narrative in English, classical and contemporary Spanish poetry.

But he did not take care of himself and his unhealthy habits did nothing to treat the aneurysm he suffered from. His heart failed a few days after man first set foot on the moon. In 1969, those in love with his poetry could only half console themselves by reading Los soliloquios (which, together with the posthumous edition of Autopía, constitute a more condensed and experimental stage). Later on, re-editions, texts rescued by friends such as Antonio Fernández Molina and Rosendo Tello, the 1983 edition of his complete works… would keep the poet’s flame alive.

References

- Antonio Ibáñez (2004). Miguel Labordeta. Poeta violento idílico (1921-1969). Zaragoza, Biblioteca Aragonesa de Cultura.

- Rolde. Revista de Cultura Aragonesa, nº 67-68, 1994. Monographic issue coordinated by Antón Castro.

- Turia, nº 96, 2010. Monograph dedicated to Miguel Labordeta.

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa on line: http://www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com/voz.asp?voz_id=7561

- Obra completa, edited by Clemente Alonso Crespo, was published by El Bardo. It was presented on 23 April 1983 as the official opening of the Teatro del Mercado in Saragossa.

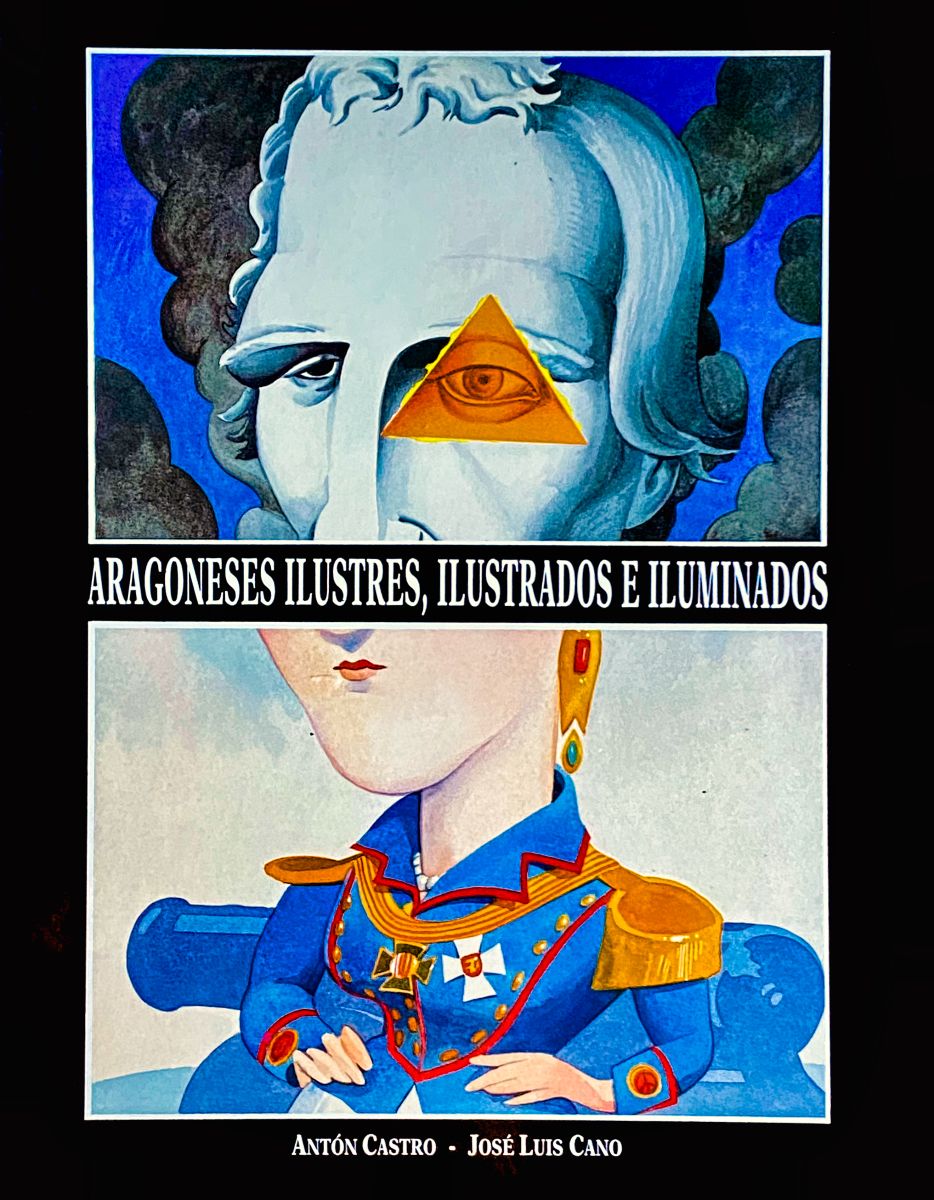

- Antón Castro (1993). “Miguel Labordeta, el orangután celeste”, en Aragoneses ilustres, ilustrados e iluminados (230-235). Zaragoza, Gobierno de Aragón.

(Magnificent studies have been devoted to Miguel Labordeta and his generation. Here we highlight just a few basic references, as well as other references throughout the educational proposals).

Teaching activities

The poet’s styles and influences

After reading it, please answer: In what style could Miguel Labordeta’s poetry be classified, or is it rather difficult to pigeonhole? Where do you think he fits better: as a predictable, conventional and orthodox poet, or as a non-conformist and heterodox poet? Was he attracted to the artistic avant-garde?

Look up the meaning of the currents he cites and which are marked in bold:

In his different creative stages it is easy to identify traces of Dadaism, surrealism, expressionism, existentialism, social poetry, concretism, visual poetry or even elements distantly related to the American beat generation.

In part of his work, specialists also detect the influence of the Generation of 1927 (including some traits of earlier authors such as Unamuno and Juan Ramón Jiménez), contact with Postism, and observe traces of Freud’s psychoanalysis, Jung’s unconscious, Marxism, the world of science fiction, oriental cultures, etc.

Also look up the meaning of the terms in this paragraph that we have marked in bold.

The Saragossa wormhole

Why do you think Miguel Labordeta used such an unpleasant term to refer to Saragossa? Maybe it was a bit unfair?

The “rancio” atmosphere was not exclusive to Saragossa, but after all, it was what Miguel knew first hand. His return from Madrid, where (despite a similar climate of oppression) he had been able to connect with fundamental elements for literary renewal, must have inspired him with this metaphor.

After the war, the Saragossa of the young Labordeta was, like the rest of Aragon and Spain, a place that was not very conducive to creativity. Many authors speak of a cultural wasteland, in a climate of repression and scarcity. Thousands of artists, writers, scientists, teachers (of those who saved their lives after the conflict) had had to go into exile. And others who remained would live in what has been called an “internal exile”.

Nevertheless, there were notable attempts to do things differently. From 1947 the Aragonese capital witnessed the activities of the Pórtico Group which, promoted by the bookseller José Alcrudo, introduced abstract painting and informalism through various exhibitions of works by artists such as Fermín Aguayo, Alberto Duce and Santiago Lagunas. Pórtico (continued in the so-called Saragossa Group with Ricardo Santamaría and Juan José Vera, among others) opened the way for post-war avant-garde painting in Spain.

Also from the 1940s, the Saragossa film club tried, against all odds, to build an original audiovisual culture, which would later bear fruit in the Saracosta or, from 1957, in the constitution of a production company such as Moncayo Films.

Find out more about the Grupo Pórtico: what kind of art they represented, who were their creators, what exhibitions they promoted (only in Saragossa or in other places? Did they have any later influence, for example in the 1960s?)

Madrid wasn’t in the best of moods either, but…

Miguel Labordeta’s revolutionary poetry and his initiatives fit in with this need to “shake off the dullness”, to propose alternatives to an official culture that was too subject to convention and academia. For this reason, his trip to Madrid was crucial in capturing a multitude of influences that would determine his work. There he came into contact with a series of writers whose only possibility of rebellion was through forms and aesthetics different from the official ones (although on occasions they would also derive this rebellion towards contents, messages and vital attitudes, for example towards social poetry).

Search the internet for information about these writers, and match them with the definition that best fits each of them.

| 1. Vicente Aleixandre | a) An exponent of uprooted poetry, after leaving Franco’s prisons, he burst onto the scene with the collections of poems Tierra sin nosotros y Alegría. |

| 2. Gabriel Celaya | b) Poet of the Generation of ’27, from Seville, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1977. |

| 3. Carlos Edmundo de Ory | c) A poet from La Mancha, he moved from postism to realism. In his last years he spent long periods in Calaceite, where he is buried. |

| 4. Antonio Buero Vallejo | d) Basque poet, he evolved from existentialism towards social poetry. |

| 5. José Hierro | e) The tragedy of the individual is at the centre of his dramatic work: in the 1940s his A Ladder Story has a clear denouncing component. |

| 6. Ángel Crespo | f) Born in Cadiz, he is considered the main representative of Postism (post-surrealism). |

Solutions: 1-b; 2-d; 3-f; 4-e; 5-a; 6-c

Miguel Labordeta’s work, eclectic and original, obeys many of these influences.

A very mature and introspective first work

The resignation from his doctorate did not go down well with the family. But Miguel had returned from Madrid with papers and sketches of what was to be his first book.

About the first stage of Miguel’s work, critics say: “The lyrical subject searches for his lost identity in the midst of chaos and the imminence of death. This tragic consciousness is steeped in a prophetic vision of art rooted in romantic and modernist poetics. Although his verses are close to surrealism in technique – hermetic images, syntactic disjointedness and the use of collage – they are imbued with a realist background that embraces the historical circumstance”.

This is a reprint that the Institución Fernando el Católico added to its catalogue, as part of its “San Jorge” collection, in 1988. With a foreword by his brother José Antonio, it respects the original appearance, with a drawing on the cover by the great cartoonist and humorist Antonio Mingote.

The author of the prologue says that Miguel’s was “a voice which, from the moment it appeared in 1948, annoyed the manipulators of official culture with its truth and strength”. Who do you think he is referring to, why do you think he might be annoying, and does it have something to do with the fact that his book, conceived in 1951 under the title Los nueve en punto, ended up being published ten years later as Epilírica?

Choose a poem that strikes you at first glance.

(Suggestions: “Mirror”, “Elegy to my own death” and “Morning”).

What does it suggest to you, what inspires you: joy, sadness, both, neither, another feeling? Is it a love poem or not? Who is the speaker, if there is one? What is the main theme or themes of the poem? On the more formal aspects… Are there rhymes, punctuation marks, and do you notice any internal rhythms (a read aloud may help you find them)?

Look up the definitions of “versos libres”, “versos blancos” and “versos sueltos”: to which does the rhyme and meter best fit in the Labordeta poems you see?

In the poem “Soledad con algo de lamento”, he says: “mis buenos padres / ya casi desmayados / rojaban a Dios / por aquel pobre hijo inútil / viejo de estos 25 estíos”.

As well as planning his relationship with his parents to some extent… Miguel Labordeta feels old at the age of 25. The very title of the book, Sumido 25, has a bearing on that feeling, on that uneasiness. It is an age that will seem “very old” to you, although your parents and teachers will not think the same.

The poet defined his own work as “cathartic and purifying”. Look up the meaning of these terms in the dictionary. In the sense that it is intertwined with a “purifying” and “liberating” sense… do you think he is right in defining it that way? Have you ever experienced relief in making your feelings or something intimate clear, even if it is by writing it down just for yourself, by shouting it out in a secluded place or by sharing it with someone you trust?

The Niké’s club

The Niké café was set up in 1940 in Requeté Aragonés street (which in 1979 would recover its pre-war name of Cinco de Marzo) in Saragossa. It operated until the spring of 1969.

As we already know, in the 1950s Labordeta organised gatherings there, from where he promoted his “Oficina Poética Internacional” (International Poetry Office). The name itself indicates a desire to break out of confinement, to counter oppression through the weapons of words, humour and creativity: the “optical” manifestos, the “citizens of the world” cards already indicated this desire to break down localisms and broaden horizons. It was a revulsive for literary creation in Aragon (as was the Portico Group for the plastic arts).

Without being a continuous hive of activity (the Niké has sometimes been mythologised as if it were the centre of the life of the members of the peña, when most of them attended to their tasks regularly in other environments), it is undeniable that many initiatives came out of it: magazines, publishing houses, literary collections? You have been able to see all this in more detail, as well as the names of the people linked to this environment.

Let’s focus on some of these people. Find out about these six poets and try to relate each one of them to the work that corresponds to him or her:

- Julio Antonio Gómez a) Ese muro secreto, ese silencio

- Raimundo Salas b) Las piedras y los días

- Guillermo Gúdel c) Los pasos cantados

- Luciano Gracia d) Acerca de lo oscuro

- Rosendo Tello e) Al oeste del lago Kivú los gorilas se suicidaban en manadas numerosísimas

- Fernando Ferreró f) Hablan los días

Solutions: 1-e; 2-b; 3-c; 4-f; 5-a; 6-d

Find out more about some of them. For example, Julio Antonio Gómez had a very tormented biography due to the repression of homosexuals at the time. Did you know that until democracy arrived in Spain, homosexuality was punishable by prison?

Some suggestions and recommendations:

- Various authors (1984): OPI-Niké. cultura y arte independiente en una época difícil. Zaragoza, Ayuntamiento. The two-volume work was presented as part of a commemorative week at the Teatro del Mercado, filled with poetry readings and recitals.

- Benedicto Lorenzo de Blancas (1989): Poetas aragoneses. El grupo del Niké. Zaragoza, Fernando el Católico Institution.

- In 2003, the music group Monte Solo published the album-book 25 canciones y poemas de la OPI Niké en su 50 Aniversario

- In 2014, Ignacio Escuín shot a short film about Café Niké.

Poetry for peace

In his Epilirica, along with other poems such as “Salutation to the people in spring” and “A thirty-year-old man asks for the word”, Miguel Labordeta included the text “Kill each other. Severe warning from a citizen of the world”.

You can listen to it in different files distributed on platforms such as Youtube, but we reproduce it here for you to read it in private, or for you to share a collective reading in class.

Mataos

pero dejad tranquilo a ese niño que duerme en una cuna.

Si vuestra rabia es fuego que devora tal cielo

y en vuestras almohadas crecen las pistolas:

destruíos aniquilaos ensangrentad

con ojos desgarrados los acumulados cementerios

que bajo la luna de tantas cosas callan

pero dejad tranquilo al campesino

que cante en la mañana

el azul nutritivo de los soles.

Invadid con vuestro traqueteo

los talleres los navíos las universidades

las oficinas espectrales donde tanta gente languidece

triturad toda rosa hallad al noble pensativo

preparad las bombas de fósforo y las nupcias del agua con la muerte

que han de aplastar a las dulces muchachas paseantes

en esta misma hora que sonríe

por una desconocida ciudad de provincias

pero dejad tranquilo al joven estudiante

que lleva en su corazón un estío secreto.

Inundad los periódicos las radios los cines las tribunas

de entelequias estructuras incompatibilidades

pero dejad tranquilo al obrero que fumando un pitillo

ríe con los amigos en aquel bar de la esquina.

Asesinaos si así lo deseáis

exterminaos vosotros: los teorizantes de ambas cercas

que jamás asiríais un fusil de bravura

pero dejad tranquilo a ese hombre tan bueno y tan vulgar

que con su mujer pasea en los económicos atardeceres.

Aplastaos pero vosotros

los inquisitoriales azuzadores de la matanza

los implacables dogmáticos de estrechez mentecata

los monstruosos depositarios de la enorme Gran Estafa

los opulentos energúmenos que en alza favorable de cotizaciones

preparáis la trituración de los sueños modestos

bajo un hacha de martirios inútiles.

Pisotead mi sepulcro también

os lo permito si así lo deseáis inclusive y todo

aventad mis cenizas gratuitamente

si consideráis que mi voz de la calle no se acomoda a vuestros fines suculentos

pero dejad tranquilo a ese niño que duerme en una cuna

al campesino que nos suda la harina y el aceite

al joven estudiante con su llave de oro

al obrero en su ocio ganado fumándose un pitillo

y al hombre gris que coge los tranvías

con su gabán roído a las seis de la tarde.

Esperan otra cosa.

Los parieron sus madres para vivir con todos

y entre todos aspiran a vivir tan sólo esto

y de ellos ha de crecer

si surge

una raza de hombres con puñales de amor inverosímil

hacia otras aventuras más hermosas.

Miguel Labordeta’s brother, José Antonio, read this poem in the Spanish Parliament, where he was a member of parliament, in 2003, on the occasion of the Spanish government’s support (against the opinion of the majority of the population) for the US military campaign in Iraq.

As you can see, poetry is more than an exercise in style, in aesthetics. We can talk about fabulations, about cosmic visions, but an idea, a message? becomes more powerful if it is expressed by appealing to the intimate feelings that poetic language explores, “touching the fibre”. Creativity and imagination can be powerful instruments of peace, of change, of freedom…

Listen and watch Miguel Labordeta

The project “The booksmovie” collects on Youtube readings of many poets, Aragonese or not. We recommend these two links:

The documentary Miguel Labordeta. Biografía interior (1989), with a script by his brother José Antonio and Antonio Artero (the latter, by the way, author of a television adaptation of Oficina de horizonte).

Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people

Download from this link the PDF of the publication Illustrious, enlightened and enlightened Aragonese people, by Antón Castro and José Luis Cano, published by the Government of Aragón in 1993.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: