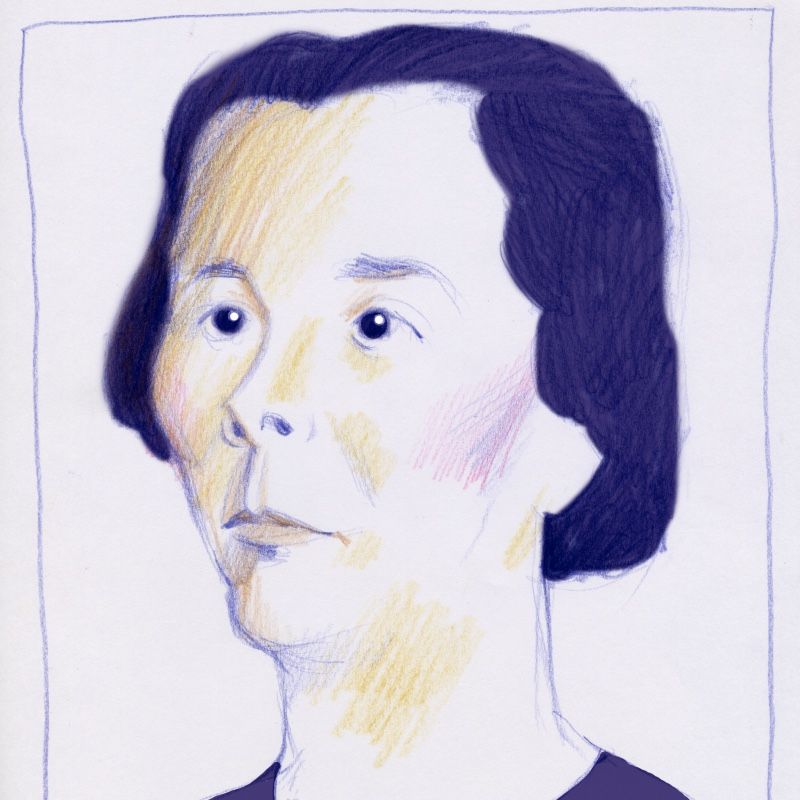

María Domínguez

The awakened voice, the rescued voice

Pozuelo de Aragón, 1882 – Fuendejalón, 1936

The first woman to hold the office of mayor in Spain under a democratic system was the daughter of a farm labourer. María Domínguez Remón governed the Gallur Town Council between July 1932 and February 1933. But, although this was important, it would remain an anecdote if we did not take into account the context and the rest of her life: a life of work, continuous effort and self-improvement.

María Domínguez Remón, daughter of Sixto and María, went to school very little. The months of the year dictated her chores, like those of so many others, whether it was gleaning, harvesting grapes or picking olives, among many other tasks in the fields and in the house. In his free time, he read everything he could get his hands on (printed matter, romances, stories…), much to the chagrin of his mother, who probably thought that to stray from the stipulated role could only bring him misfortune.

Life

“Maria the fool”, she was called by those who saw her as shy, not looking men in the face (she would use this nickname with ironic intent in some of her journalistic writings), following the dictates of the family. This obedience led her to marry at the age of eighteen to a man of bad character who mistreated her. The humiliation and vexation lasted seven years: the time it took María to flee to Barcelona, where she worked as a servant. A determined woman, large of body and strong of mind, defying her husband’s accusations, she returned to Pozuelo; with her savings in Barcelona she bought a sewing machine that allowed her to earn her own living.

She began to give free rein to her passion for reading and writing: in 1914 she sent an opinion piece to the Madrid newspaper El País, which had republican and socialist affinities. The editor of that newspaper, Roberto Castrovido, viewed it with a certain paternalism, describing it as “a naïve cry of protest from a peasant girl”, but the article was published.

Teacher

From then on, María maintained an intense cultural life. While continuing to sew, she worked as a teacher in Saragossa (she would later obtain her official qualification), studied at the School of Arts and Crafts and began to contribute regularly to the newspaper Ideal de Aragón, the organ of the Partido Republicano Autónomo Aragonés, directed by Venancio Sarría. In her articles (which she usually signed with pseudonyms such as “Imperia” or “Almina”) she was anti-war and opposed to the death penalty.

For a time she lived in Navarre, working as a teacher in the Baztan valley and obtaining her degree at the Pamplona Teacher Training College. She apparently contracted influenza around 1918 and, quite ill, returned to Saragossa. Although she had been separated from her husband for several years, she must have experienced a certain liberation when he died in 1922. Shortly afterwards she married Arturo Segundo Romanos, a socialist shearer from Gallur. The couple settled in this town on the banks of the Ebro and organised the local section of the General Workers’ Union. María returned to her journalistic collaborations, this time with the Saragossan socialist weekly Vida Nueva and in Avance, in Tolosa. She was an advocate of the emancipation of the underprivileged and of women, and was hopeful when the Republic was proclaimed on 14th April 1931.

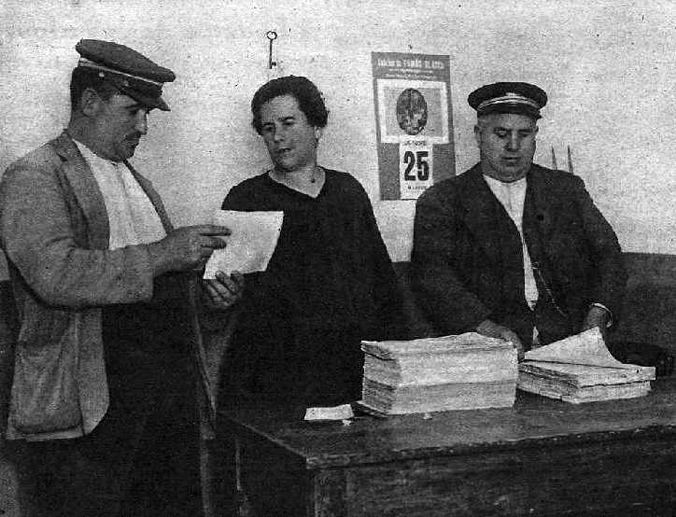

Mayoress of Gallur

In the summer of 1932, a crisis within the Gallur municipal council, which had a socialist majority, led the civil governor of the province of Saragossa to appoint a management commission chaired by her, who had taken part in the 17th UGT Congress (at which Juián Besteiro was to replace Francisco Largo Caballero as head of the union). Her work in the City Council lasted only a few months, but she had the opportunity to promote policies that improved workers’ lives and dignified education.

When in February 1933 the management commission was dissolved by law, María resigned from her post, satisfied that she had conceived of the mayor’s office as a service to the people and never as an object of ambition or a means to a political career. La Tacona (as she was affectionately called by her students at the Gallur school) returned to her classes and her contributions to the press. Perhaps her popularity as the only woman mayoress in Spain facilitated the publication of a series of her lectures in a compilation volume by the Madrid publishing house Castro. Opiniones de mujeres included the following contents: “Feminismo”, “La mujer en el pasado, en el presente y en el porvenir”, “El socialismo y la mujer” and “Costa y la República”. It also had a foreword by the precocious lawyer Hildegart Rodríguez.

Her texts have a great deal of personality: in them, the author offers her own original, intelligent and ironic view of the world and current affairs. She advocates women’s equality, freedom of thought, universal suffrage, women’s suffrage, divorce, freedom from prejudice, education and culture as engines of change, self-improvement, freely chosen love, and so on.

On 18 July 1936 everything collapsed. The failure of the coup d’état by military traitors to the Republic unleashed a civil war that split Spain and Aragon in two. The political significance Maria had acquired made her hostile to the rebels, who had imposed themselves on western Aragon. She took refuge with Arturo at her sister’s house in Pozuelo, but a few days later they were both arrested and locked up in a dungeon, from which they were taken to a van bound for Fuendejalón. On 7 September 1936, shots were fired at the cemetery walls and the body of María Domínguez was found in their path.

References

- María Domínguez (1933): Opiniones de mujeres. Madrid. Foreword by Hildegart Rodríguez. Reissued in 2005 (Zaragoza, Diputación Provincial, with introduction by Julita Cifuentes and Pilar Maluenda). There is another reprint by Pregunta Ediciones (2021). Information about this book:

- http://www1.dpz.es/prensa/elcuartoespacio/2005/numero4/num4pg18.pdf

- María Domínguez, la palabra libre. Documental (28 minutos) directed by Vicky Calavia, 2015.

- Rosa Montero (2005): “Para honrar la memoria”. Column of El País Semanal (24 de abril de 2005): https://elpais.com/diario/2005/04/24/eps/1114324016_850215.html

- Biography on wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mar%C3%ADa_Dom%C3%ADnguez

Teaching activities

María after María

Spain’s first female mayor was buried in a mass grave and her memory was also buried. She had had no descendants, the couple’s property had been confiscated… and moreover, for decades, Franco’s dictatorship had glorified the fallen of his side and ignored the dead of the defeated.

In the 1990s, the historians Julita Cifuentes and Pilar Maluenda (who had methodically researched the repression during the Civil War in the province of Saragossa under the tutelage of Julián Casanova) made public some findings about María Domínguez and a few articles and reports began to remember her and do justice to her memory. In 1999 the Diputación de Zaragoza awarded her the Santa Isabel Medal posthumously and a few years later her Opiniones de mujeres was republished. A Foundation was created in her name, dedicated to promoting the values for which she fought, and a series of tributes and acknowledgements followed.

In January 2021, her remains were recovered from the grave where they had been buried for more than eighty years. DNA analysis allowed them to be identified and they were given a dignified burial in the Fuendejalón cemetery.

Look for news about the exhumation of corpses from the Civil War. Some people think that this would reopen old wounds and rekindle revenge. Others consider that in order to turn the page and move forward in history, one must read all the lines, even if they are crooked and painful, and that everyone has the right to search for their dead and to bury them with dignity if possible. [No opinion or value judgement is asked for: it is an invitation to reflect on a complex subject.]

The feminism of María Domínguez and other women of her time

From her very inclusive feminism in pursuit of equal rights and opportunities, one of the fundamental things María Domínguez demanded was the right to vote for women.

When was women’s suffrage established in Spain?

The feminism of our protagonist has a great social projection, as it is linked to the integral formation of the person, to education and culture as tools for the transformation of society. Her own biography is a continuous breaking of moulds, progressing from below, with tenacity and defying a destiny that seemed marked from birth. María Domínguez is an extraordinary case, but in her time there were other women who also showed courage or raised the flag for equality between men and women.

These six women were great feminists, each from her own point of view and with her own personality, and even with political differences between some of them. Do some research on them and match their names with the corresponding phrase or idea.

- Clara Campoamor

- Victoria Kent

- Carmen de Burgos

- María de la O Lejárraga

- María de Maeztu

- Amparo Poch

a) A very successful playwright, overshadowed by her husband (also a playwright, for whom she wrote most of her plays in the shadows), she founded several feminist organisations.

b) Pedagogue, director of the International Residence for Young Ladies.

c) Lawyer and Member of Parliament, Director General of Prisons during the Second Republic.

d) Journalist, writer, translator and women’s rights activist.

e) Doctor and writer, libertarian activist, founder of the magazine Mujeres libres.

f) Lawyer and leading advocate of women’s suffrage.

1-f, 2-c; 3-d; 4-a; 5-b; 6-e

Except for Carmen de Burgos, who died in 1932 in Madrid, what are the places of death of the other five women? Why did none of them die in Spain?

Campoamor (Lausanne, Switzerland), Kent (New York, USA), Lejárraga (Buenos Aires, Argentina), Maeztu (Mar del Plata, Argentina), Poch (Toulouse, France). They were luckier than María Domínguez because they survived the Civil War, but were unable to return to their country, under a regime that persecuted their ideas and those who defended them.

As an Aragonese, it would be very interesting to delve deeper into the figure of Amparo Poch y Gascón. Wikipedia provides a comprehensive and well-documented approach to her figure.

The collection of Ideal de Aragón

War in Europe

In her articles in Ideal de Aragón published around 1916, María was anti-war. For her there is only one weapon: “Let the book be our weapon of combat”. Europe was bleeding to death at the time in the Great War, and republican and socialist principles coincided with a certain theoretical pacifism. However, he is also particularly critical of the side led by Germany (more aligned with conservative ideas), and more favourable to those represented by countries such as France and the United Kingdom, with more liberal and democratic traditions.

Look up information about World War I. What was Spain’s position in World War I? Who were the Alliedophiles, who were the Germanophiles?

The importance of school

María Domínguez was a woman of the people, a hard worker, and a teacher by vocation. During her brief term as mayor, she transferred her personal experience to improving living conditions in the world of work and education.

On the one hand, she ensured compliance with the labour laws of the Republic, and created rural labour exchanges to reduce unemployment. As for education, he set up a unitary school for boys and girls, allocated municipal funds to whitewash the walls (so that the school would be clean and dignified), to hire cleaners so that the children would not have to clean (which was the custom in many places) and to buy sacks of coal for the cookers, so that the pupils would not have to bring it from home.

Do some research at home: ask your parents and (even better if possible) your grandparents about their memories of their school days: their games, how they studied, what their schools, teachers were like. Select what interests you most and tell them about it. Share these experiences of your elders in class.

María Domínguez currently gives its name to the primary school in Gallur. What is the name of your school or high school and is it a name of a person? If so, collect information about it.

A tremendous evil to combat

During her youth, María Domínguez suffered violence in her own home. María suffered abuse, but she did not accept it and left her husband in defiance of social norms, in defiance of the unwritten law of her own neighbours. Unfortunately, domestic abuse and gender-based violence have always existed. Today we have more information, there are more reports, more awareness, more resources… but the information that reaches us still hurts and shocks us.

What do you think is most important to neutralise and contribute to putting an end to these evils? Actions from the base, in the long term, education from an early age in values of equality and respect? Advertising campaigns to raise awareness? Other specific actions, such as tougher penalties for abusers? Perhaps there is no single answer, and everything must be taken into account, right? Surely it is also necessary to monitor low-intensity or apparently “innocent” sexist attitudes in everyday life, in our daily environment (at school, at home, among friends…). It is a good topic to discuss in the classroom.

An epilogue to María, whom the writer Rosa Montero defines as “a woman who burned with the desire to live and to do”.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: