María Andresa Casamayor

Prosperity through mathematics

Saragossa, 1720 – 1780

The Saragossa mathematician María Andresa Casamayor y de la Coma was the first woman known to have published a scientific book in Spain. She did so during the first half of the 18th century and, judging by the content of her work and the way it is presented, her intention was to “democratise” knowledge and provide her fellow citizens with useful tools so that they could prosper in their daily tasks.

Born on the banks of the Ebro in 1720, on 30 November, St. Andrew’s Day (hence her name, which, incorrectly transcribed by a later commentator, has been known until recently as Andrea), she was one of the eldest of nine children born to a merchant father.

Life

The Aragon in which this pioneer of science lived experienced one of the most flourishing periods in its history. It had left behind the ravages of the War of Succession, and with the arrival of the Bourbons to the throne, the theses of the Enlightenment gradually made their way into the country. This cultural current held that ignorance and superstition had to be combated, and that reason, science and education had to be used to promote economic progress and improve society.

Only a minority accepted such an ideology, which could change the social order. But it was taken up by a wealthy elite, including María Andresa’s family, as she received a thorough education, which was unusual for a woman in the Spain of her time. During her childhood, there were still no girls’ schools in Saragossa and mixed schools were unthinkable. A few privileged girls had private tutors. But, as a rule, the girls only received notions of Catholic doctrine and housework. Learning to read and write, for example, was considered secondary.

Work

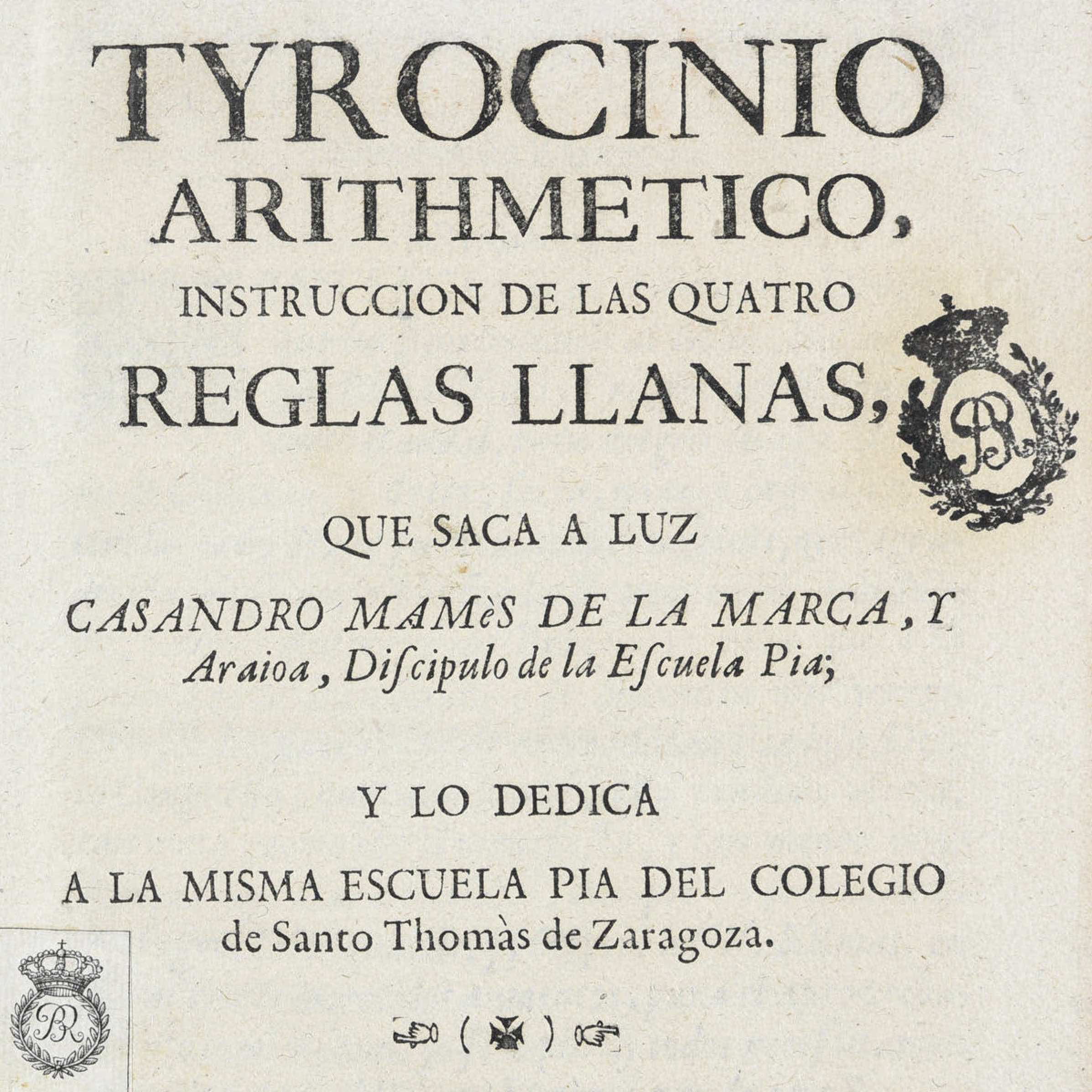

Maria Andresa reached an admirable level in the mathematical sciences and worked on complex arithmetical calculations to open up new avenues of research. However, in the first book she wrote, she abandoned these complexities to explain in a very simple way the most basic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. He brought it to press in 1738, before he was eighteen years old, and entitled it Tyrocinio Artihmetico, i.e. Arithmetical Learning.

There were already other publications on the same subject, although they were all more difficult to understand. Maria Andresa’s book provided accessible examples taken from real life in areas such as commerce, agriculture and animal husbandry. It also included a complete set of the weights and measures in force in Aragon (there were many, whose values varied in some cases depending on the region), as well as the different currencies in use (also many), with detailed tables of equivalences.

Casandro Mamés de la Marca y Araoia

As at that time nobody would believe that a mathematics book written by a woman existed, she had to sign the text with a male name, Casandro Mamés de la Marca y Araoia, an anagram of her own. That is, he reversed the order of the letters of his real name to compose his pseudonym.

He dedicated the book to the Escuelas Pías school in Saragossa, of which “the author” acknowledged himself to be a disciple. And this may be another of the keys to a text in which several principles prevail: to be accessible, didactic, useful and to offer tools for prosperity. The Piarists settled in Saragossa in 1731 and with them they brought the primitive philosophy of the order, founded in 1597, in Rome, by José de Calasanz from Huesca: the free education of the poorest, a revolution since it could provoke enormous changes in society. Moreover, in order to ensure that the education would enable the pupils to earn a living when they reached adulthood, they paid special attention to mathematics and its practical applications. The powerful saw all this as a threat and tried to eliminate the order, which went through deep potholes, although it eventually spread throughout Europe and to other continents.

Shortly after publishing her book, the young mathematician’s father died and the family foundered in a sea of debt. Despite this, Maria Andresa never married, nor did she seek refuge in the Church, almost the only viable means of survival for a woman of her time in her circumstances. She went to work outside the home to make ends meet, an exception to the norm. She taught girls in public schools for a modest salary.

She wrote another work, this one on higher mathematics, now lost. Neither she nor her brothers, who inherited it, published it, as it was not profitable. It was only read by a few scholars and onlookers, who praised it.

Little else is known about this exceptional woman from Saragossa, to whom the scholars of her time dedicated few but praiseworthy lines. She enjoyed knowledge and its dissemination at a time when both activities were forbidden to women. And although most of her life and achievements are unknown, she does not appear in any textbook and no one has ever heard her name mentioned, she is the first Spanish woman scientist whose work has been published. She was, however, hidden under a male pseudonym.

References

- Julio Bernués, Pedro J. Miana (2019): “Soñando con números, María Andresa Casamayor (1720-1780)”, Suma: Revista sobre Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de las Matemáticas, 91, pp. 81-86.

- María José Casado Ruiz (2006): Las damas del laboratorio. Mujeres científicas en la historia. Barcelona: Debate.

- R. Domínguez (1999): La enseñanza de las primeras letras en Aragón (1677-1812). Zaragoza: Mira.

- Fico Ruiz (2017): Aragoneses olvidados. Zaragoza: Anorak.

Teaching activities

Women’s education in the 18th century

As the eighteenth century progressed and the Enlightenment spread, there was growing concern among the wealthy classes for the education of children and young people, both boys and girls. However, female education was not yet regulated and was less widespread than male education.

The custom of the ancien régime of separate education for the sexes continued. And there was a clear difference between the first elementary schools for girls, run by public bodies, which taught the first letters to the lower classes, and the schools run by women’s religious orders, for girls of higher social standing. In all the centres, however, Christian doctrine and domestic work, such as sewing and embroidery, were the main subjects.

Over time, the religious schools also began to include new subjects such as arithmetic, geography and history, language and music. But their numbers were few, so many aristocrats were educated by private tutors, while girls from the middle classes learned at home, supervised by their mothers. Lessons included French and dancing, taught by hired teachers, who advertised themselves as such in the press.

Find information about women’s education in the 18th century and answer true or false to the following statements:

| In the 18th century all women received an education | T | F |

| University studies were only for boys | T | F |

| Boys and girls studied the same subjects | T | F |

| Men and women could teach equally | T | F |

| Girls could receive some form of education | T | F |

| Education was compulsory for boys | T | F |

| Education depended on the will and possibilities of families | T | F |

| The Enlightenment defended education as the only means of attaining knowledge | T | F |

Solution: 1-F / 2-T / 3-F / 4-F / 5-T / 6-F / 7-T / 8-T

The “escolapios” (piarists), in Saragossa

Calasanz perceived the importance of mathematics and science for the future and repeatedly instructed that both subjects should be taught in his schools and that his teachers should have a firmer grounding in these subjects as they could help pupils to prosper in business and in life.

Initially, Piarist schools, like all schools, were open only to boys. Not for girls.

Andresa’s family was well-to-do and as such provided education for their sons, but also for their daughters, with private teachers. As has been said, Andresa soon excelled in Mathematics and came up with a way to make it more accessible to all.

Who studied at the Piarist

Some authors claim that Goya himself studied at the Piarist. Do you know who else studied there?

Here are some of their illustrious students from that period (there are even streets named after them), look up some information about them.

José Palafox

Francisco Bayeu

Santiago Sas

Pedro María Ric

Other women mathematicians

Match these names of women mathematicians from history with their work and their times

|

Hypatia of Alexandria |

Age of Enlightenment | Self-taught French mathematician and physicist. She was one of the pioneers of the theory of elasticity. Under the pseudonym Antoine Auguste Le Blanc, she signed several articles sent to the mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange. |

|

Ada Lovelace 1815 – 1852 |

Present

|

Mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. She commented on great works of classical Greek mathematics. She is one of the first known female scientists. |

|

Mariam Myrzakhani 1977 – 2017 |

Late roman period | A British mathematician and programmer, she wrote the first algorithm for an analytical machine, which is why she is considered the mother of computer science and programming. |

|

Sophie Germain 1777 – 1831 |

Industrial Revolution | Iranian mathematician, she was the first woman to win the Fields Medal, considered the Nobel Prize in Mathematics. Her most important contributions to science are in the field of geometry. |

Solution: 1-C-II / 2-D-III / 3-B-IV / 4-A-I

Find out more about them and describe the environment in which they developed their activity as scientists and compare it with that of María Andresa.

Which one is the most similar to our protagonist? Why?

Are there any women in your family who work in science? Do you know what they do?

Andresa’s work and her signature

Andresa wrote her first and only surviving book Tyrocinio Artihmetico (arithmetical learning) when she was 17 years old and, unlike other manuals of the same period, it is characterised by its clearly didactic and practical purpose. As mentioned in the text:

it provided accessible examples from real life in areas such as commerce, agriculture and animal husbandry. And, in turn, it included a complete set of the weights and measures in force in Aragon (there were many, whose values varied in some cases depending on the region), as well as the different currencies in use (also many), with detailed tables of equivalences.

Look up some measures of weight, length and capacity used in Aragon in the 18th century, such as the arroba, the fanega, the cahíz, the libra, the alquez, the cántaro or the vara. Also look for some of the coins that existed in Aragon at the same time, such as the Jaquesan pound.

Have you found many? It was useful to know their equivalence so as not to be cheated in business, wasn’t it?

Casandro Mamés de la Marca y Araioa is the pseudonym used by Andresa to sign her first and only surviving book. She had to do it with a male name because nobody would have believed at that time that a woman was capable of writing a book on Mathematics. This pseudonym is a perfect anagram of her full name, the same letters that compose it distributed in a different order.

CASANDRO MAMÉS DE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA

CASANDRO MAMÉS DE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA MARÍA

CASANDRO MAMÉS DE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA ANDRESA

CASANDRO MAMÉS DE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA CASAMAYOR

CASANDRO MAMÉS DE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA DE LA

CASANDRO MAMÉSDE LA MARCA Y ARAIOA COMA

Do you know what an anagram is? Try to form an anagram with the letters of your full name. You will see how easy it is.

As a complement to these activities, it is recommended to watch the following documentaries

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: