Ana Abarca de Bolea

Between seclusion and literary excellence

Saragossa, 1602 – Casbas, 1686

Ana Francisca Abarca de Bolea y Mur was born into an influential Aragonese noble family based in Saragossa, Huesca and Siétamo. To this illustrious lineage would belong, many years later, the Count of Aranda. Daughter of the writer, humanist and poet Martín Abarca de Bolea and Ana de Mur, at the age of three she was taken to the Cistercian monastery of Santa María de la Gloria in Casbas, at the foot of the Sierra de Guara, where she was to spend her entire life.

This monastery had a prestigious girls’ school, where the little girl received a thorough religious and humanistic education. After suffering the early death of her parents while still a teenager, she continued her education and became a cloistered nun from the age of twenty-two, working as a novice mistress. Ana Abarca is a self-taught and erudite woman, always interested in learning and in creatively occupying the time left free by her religious obligations: she paints, studies, embroiders, reads, makes music and writes.

Life

In the 1640s she made very interesting contacts with cultural and intellectual circles in Huesca and Saragossa: she corresponded with the chronicler of Aragon Juan Francisco Andrés de Uztarroz and other personalities of the time and was encouraged to submit her own compositions to literary competitions, such as the funeral contest held in 1646 on the occasion of the death in Saragossa of Prince Baltasar Carlos, son of King Philip IV. A sonnet by the nun won third prize.

Around this time, Ana Abarca de Bolea began to associate with the group based in Huesca around the patron and scholar Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa. She met Baltasar Gracián, the canon of Huesca Cathedral Manuel de Salinas, the poet Francisco de la Torre and the historian Fray Jerónimo de San José. His relations with this circle are mostly epistolary, but he also receives occasional visits to the monastery, during a summer stay in the castle of Siétamo and makes personal visits to Saragossa and Huesca.

Work

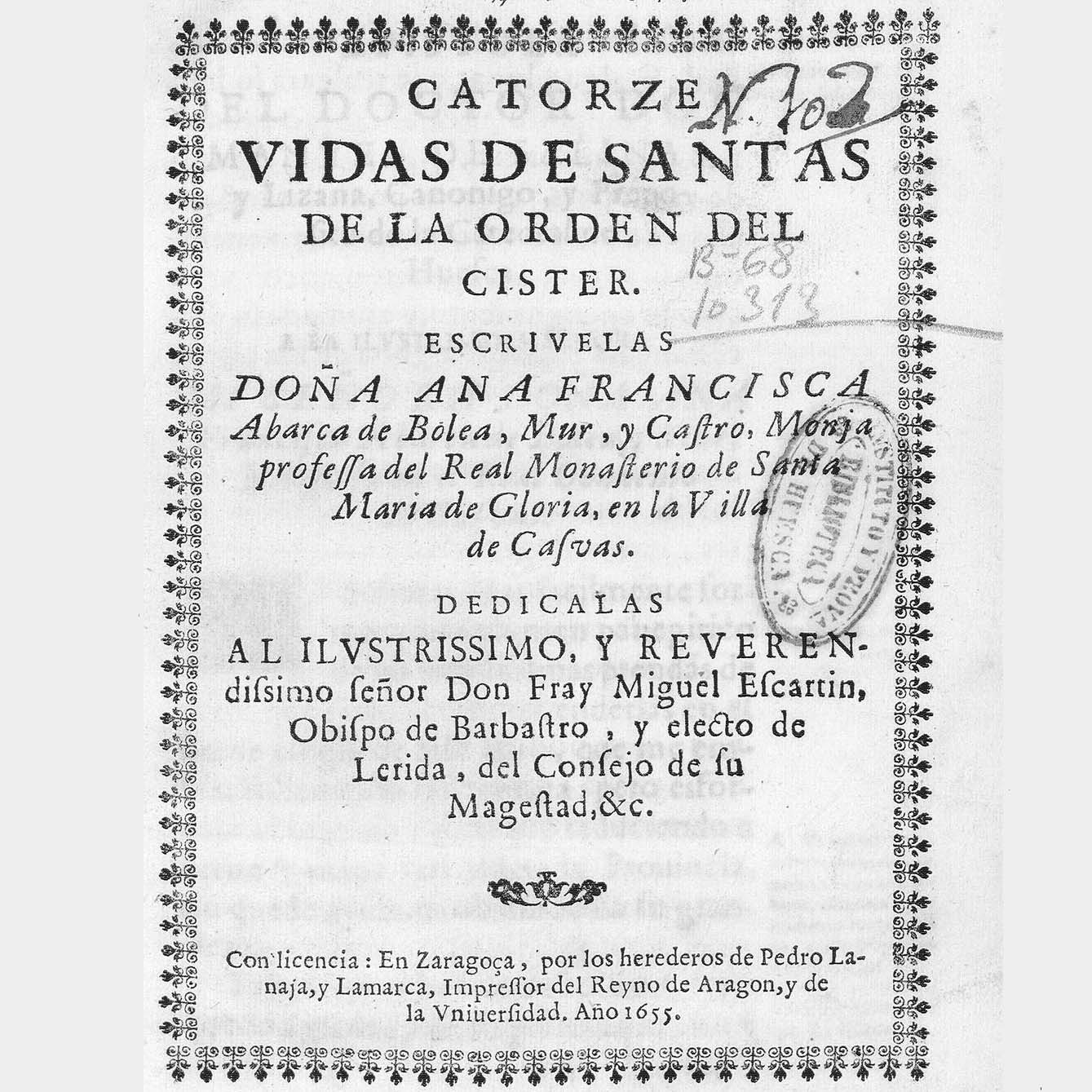

In 1650, his nephew Luis Abarca de Bolea, Marquis of Torres, a great fan of poetry, promoted a competition on the occasion of the wedding between Philip IV and Mariana of Austria. The nun writer submitted a poem on the Purification of the Virgin, which won second prize and was later included, with variations, in Vigil and Octave of Saint John the Baptist. Five years later, in 1655, her first work, Catorce vidas de la orden del Císter (Fourteen Lives of the Cistercian Order), was published in Saragossa. During these years he kept a chronicle of the events that took place in the convent. In 1671 he published the Life of the glorious Saint Susanna, Virgin and Martyr, and it seems that he was also preparing other texts dedicated to the Virgin of Gloria and Saint Felix of Cantalicio, which were never published and whose manuscripts have disappeared.

Casbas

Between 1672 and 1676, Ana Abarca was abbess of the monastery of Casbas: an important post that involved not only spiritual direction, but also the management of an enormous property, which included many places, villages and castles. It fell to her to exercise this jurisdiction as successor to the Countess Oria de Pallars, founder of the monastery at the end of the 12th century.

Freed from her responsibilities, in 1679 she published her most creative work, Vigil and Octave of Saint John the Baptist. It is a miscellaneous book containing texts of very varied genres in prose and verse. Two short novels (La ventura en la desdicha and El fin bueno en mal principio) are included within the framework of a pastoral dialogue in which anecdotes are told and romances and songs are recited: in this way, most of the poems that the author wrote during her lifetime are collected. It is poetry of a sacred and popular nature, which also includes literary testimonies with Aragonese linguistic features.

In her last years, in her old age, her niece Francisca Bernarda was her support. At that time she had the satisfaction of seeing the completion of the Baroque altarpiece of the Virgin of Gloria, which she had paid for. There is no exact record of her death, but it seems that it must have taken place around 1686.

References

- María Ángeles Campo Guiral (2007): Devoción y fiesta en la pluma barroca de Ana Francisca Abarca de Bolea: estudio de la vigilia y octavario de San Juan Bautista. Huesca, Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses.

- Francho Nagore, Paz Ríos (1980): Ana Abarca de Bolea. Obra en aragonés. Huesca: Consello d’a Fabla Aragonesa.

- Real Academia de la Historia, Diccionario Biográfico: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/17060/ana-francisca-abarca-de-bolea-mur-y-castro

- Chapter of the series “Recosiros” (directed by Vicky Calavia, script of Óscar Latas): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O9YjXMWKK90

- Chusé Antón Santamaría (2022): Ana Abarca de Bolea. Guía de lectura. Zaragoza: REA.

Teaching activities

A triangle of friendship with Lastanosa and Gracián

In 1647 Baltasar Gracián’s El Discreto was published in Huesca, financed by Lastanosa, and the patron sent a copy to Abarca. The latter wrote a tenth in praise of the book.

What is a tenth?

Stanza of ten acconsonantal octosyllabic verses

Sr. D. Juan Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, muy señor mío:

Merced divina y humana

ha sido enviarme El Discreto

y de verdad os prometo

he quedado muy ufana.

Es obra tan soberana

y tanta su discreción,

que llega a hacer un varón

tal, que el mundo viene a creer

del cielo ha de descender

quien tiene tal perfección.

Lastanosa returned another tenth whose lines ended with the same word as the lines of the nun’s poem:

De que estimes tan humana

el librito del Discreto

mi voluntad te prometo

que ha quedado muy ufana.

Tu décima soberana

parto de tu discreción,

es pasmo a todo varón,

tal que el mundo viene a creer

que debe de descender

del cielo tal perfección.

And, to finish, she responded with another poem that arranged the last words of each verse, but in reverse order.

Sr. D. Juan Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, índice de lo criado:

Del cielo tal perfección

sólo puede descender,

así lo he llegado a creer

viendo en ti tanto varón.

Admira tu discreción,

que la que es más soberana,

si la alcanza, queda ufana.

Yo de verdad te prometo

te venero por discreto,

mas no es mucho, soy humana.

Su servidora de V.M. Doña Ana Fca. Abarca de Bolea y Mur

The original manuscripts of this friendly poetic correspondence are kept in New York, in the Hispanic Society of America, and were reproduced by M.ª Ángeles Campo Guiral in her article “Tres poemas inéditos en torno a El Discreto de Gracián“, in the journal Alazet (number 3, 1991, pages 107-114).

As is often the case with many anecdotes, this one suggests many things to us. This crossroads of poems speaks to us of shared sensitivity and generosity, of poetry as a game, of creativity as simple entertainment, as an element of friendly and cordial treatment. Don’t you think that today, in one way or another, we also follow that dynamic a little? Do you exchange memes, jokes, with your friends? Do you have codes that others, especially the older ones, don’t know?

The following year, Gracián names Ana Abarca de Bolea and her father in terms of praise in his Agudeza y arte de ingenio. The Aragonese Jesuit includes her as an example in his chapter devoted to “nominal acuteness”, speaking of “the very noble and illustrious lady Doña Ana de Bolea (…) competing nobility, virtue and her rare wit, inherited from the distinguished and erudite Don Martín de Bolea, her father”.

Aragonese language author

Ana Abarca de Bolea is not the first “cultured” writer to transfer popular elements to more elaborate literary forms. But she is the first to do so in Aragon and with Aragonese. The Romance language which, in the 17th century, despite its decline, was still present in popular manifestations through oral transmission, takes literary form in the work of the nun from Casbas.

We have already spoken of her Vigilia y Octavario de San Juan Bautista: a miscellaneous work of fiction that combines very diverse forms and contents within a framework of pastoral dialogues set in the Moncayo (taking a distance, but at the same time familiarising the setting with the Guara mountain range closest to it). The protagonists combine prayer in honour of San Juan Bautista with different more mundane entertainments, including meals, songs, Christmas carols, dancing, jokes, etc. All this serves the author to bring together an abundance of unrelated and varied literary material. She does so with erudition and wit (some specialists detect the imprint of Góngora). Among the many poetic writings are three compositions in Aragonese. Two of them have a Christmas theme (“Albada al Nacimiento” and “Bayle pastoril al Nacimiento”) and the other is dedicated to praising, in the mouth of a peasant and with a humorous touch, the festivities that took place in Saragossa to celebrate Corpus Christi (“Romance a la procesión del Corpus”).

In addition to other highly recommendable contents that may arouse your curiosity… on pages 65 and 66 you can read about some literary manifestations in the 17th century and, more specifically (pages 78-79) find out a little more about Ana Abarca de Bolea, as well as read a fragment of the “Bayle pastoril al nacimiento”. It’s easy to understand, isn’t it? It is Aragonese with quite an influence from Castillian, but there are some words that will catch your attention: can you pick out any that you find difficult to understand?

The last lines of this “Bayle…” are:

Si con ramos y sonajas / oy a Belén acudimos / rajas abremos de hazernos / baylando con regocijo

What do they suggest to you? It is striking that a cloistered nun writes in such a festive and carefree tone, speaking of joys and pleasures? It happens that things are neither black nor white.

The “Albada al Nacimiento”

What is an “albada” and what time of day does it relate to? Have you heard of any other “albadas”? Look for information.

The “Albada al nacimiento” consists of eighty verses distributed in twenty “coplas arromanzadas” (octosyllables, rhyming the even-numbered verses in assonance) and has a Christmas theme, and reveals folklore customs (“cantada por Ginés y Pascual al uso de su aldea y son de la gaita” (“sung by Ginés and Pascual to the tune of the bagpipes”). There are eighty verses of religious spirit, without fuss, but rather with simplicity, candour and sensitivity, showing verbal abundance and expressive richness,

These are its first verses:

Media noche era por filos,

as doce dava el reloch,

quando ha nagido en Belén

vn mozardet como vn sol.

Naçió de vna hermosa Niña,

virgen adú que parió,

y diz que dexó lo cielo

por este mundo traydor.

Buena gana na tenido

pues no len agradejón

aquellas por qui lo fizo

y bien craro lo beyó

En fin, naçió en vn pesebre,

como Llucas lo dizió,

no se enulle si le dizen

que en as pallas lo trobón.

Mini vocabulary: por filos: in point # adú que: although # dexó: left # fizo: made # veyó: saw # enulle:enoje # trobón: found

The dwelling of Ana Abarca de Bolea. A visit to the monastery of Casbas

You will have heard of, and perhaps visited, the monasteries of Piedra, Veruela, perhaps also Rueda…. Look for some common element in all of them: what order, what artistic style do these monasteries belong to, where do they come from and what period did this style establish itself in Aragon?

Cistercian, from France, second half of the 12th century, transition between Romanesque and Gothic.

Less well known, the monastery of Nuestra Señora de Gloria de Casbas is one of the most interesting examples of Cistercian art. In the times of Ana Abarca de Bolea, this convent was in a splendid situation. Today, that grandeur can still be appreciated. Barely half an hour from Huesca, and in a very unique setting, a visit allows you to discover the environment in which the writer nun spent almost her entire life. It is advisable to find out in advance about accessibility and visiting possibilities:

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: