Al-Muqtadir

The splendour of Islamic Saragossa. The sword and the pen

Circa 1010?-Saragossa, 1082

During the Middle Ages, Islam flourished not only in the south of the Iberian Peninsula. It also developed spectacularly in other places, such as the Ebro valley and its environs. Here, the local authorities were in constant conflict with the central power established in Córdoba and, when a civil war broke out in 1031 that eventually dismembered the Caliphate of Córdoba, they took the opportunity to create an independent kingdom or taifa with its capital at Saraqusta (Saragossa).

Two dynasties of Arab origin succeeded each other on the throne, the Thujibids and the Hudids, under whom the area achieved extraordinary splendour, especially during the rule of the second of the Hudid monarchs, named Abu Yafar Ahmed ibn Sulayman. When he came to the throne in 1046, he ruled over a small territory, as his father had divided the kingdom among his five sons. But he soon reduced his brothers settled in Huesca, Calatayud and Tudela to obedience. Only his brother Yúsuf, in Lérida, maintained his rebellion for more than thirty years, until he was finally defeated and taken prisoner.

Despite the family struggles and the military pressure exerted by the Christian rulers of Castile, the young kingdom of Aragon and the Catalan counties, the Saraqusta ruler managed to extend his political and military power as far as the Mediterranean. He occupied Tarragona, Tortosa and Denia, and subjected Valencia to vassalage, making the Saragossan taifa the most powerful in the Peninsula, along with that of Seville.

In the north of his dominions, he disputed control of the cities of Graus and Barbastro with the Aragonese. In 1063, he defeated Ramiro I at the gates of Graus, who died in the battle. But a year later, Pope Alexander II decreed the Crusade – a rehearsal for those who would later go on to conquer Jerusalem – and knights from the south of France razed Barbastro to the ground and killed or enslaved its inhabitants. Given the brutality of the Christians, the king of Saragossa called for a holy war, asked for help from the whole of al-Andalus and, at the head of a powerful army, recovered Barbastro in 1065. For his great triumph he received the nickname of Al-Muqtàdir Billah, that is, “the mighty by the grace of God”.

The Aljafería

To celebrate his victory, al-Muqtádir decided to build a dream palace on the outskirts of Saragossa, as if it were straight out of a tale from The Thousand and One Nights, the Aljafería, whose name derives from one of the monarch’s names, Yafar. On the outside, its mighty walls, with ultra-semicircular towers, are as reminiscent of the Roman walls of Saragossa as they are of the first Arab castles in the Syrian desert. The interior, on the other hand, is all delicacy, with fountains and gardens, as the Qur’an describes paradise, and rooms richly decorated with sophisticated geometric and vegetal motifs in plaster, ceramics and wood. The monarch was so pleased with the result of the construction that he even dedicated a poem to it:

O palace of joy (qasr al-surur). O golden hall,

in you my desires have found their fulfilment.

If I possessed nothing else in my kingdom

I would have all that I could desire.

In the Aljafería the king ordered the creation of a great library and within its walls literary men, philosophers, men of religion, historians, experts in law, scientists and translators from all over Al-Andalus gathered, attracted by the security provided by Al-Muqtádir, and who joined the local scholars, who were already outstanding. In Saraqusta, for example, one of the best philosophical schools of Islam was born, which definitively incorporated the postulates of Aristotle and would influence medieval Christian thought. But the city was also home to musicians, doctors, mathematicians, physicists and astronomers of enormous fame, whose teachings spread throughout the Muslim world, with which the city was connected through its active river port and the waters of the Ebro, navigable to its mouth.

In the last years of his life, Al-Muqtádir, who was already very ill, handed over power to his sons. On his death, they divided the kingdom. His successor, Al-Mutamán (“he who trusts in God”), one of the most outstanding mathematicians in Europe in the Middle Ages, as well as king, continued his father’s wars against the Christians and, in turn, confronted his brother who had settled in Lérida, for all of which he had the valuable help of a paid ally, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the Cid Campeador.

References

- Mª Jesús Viguera (1995): El islam en Aragón. Zaragoza: CAI (col. Pano y Ruata), 1995.

- José Luis Corral (1998): Historia de Zaragoza 5, Zaragoza musulmana (714-1118). Zaragoza: Ayuntamiento.

- Mª José Cervera (1999): El reino de Saraqusta. Zaragoza: CAI.

- Marcos Castillo Monsegur, ed. (1987): La casa del placer (poetry). Calatayud: Sociedad de Estudios Hispano-Árabes Al-Ándalus As-Samali.

- Abú Bakr al-Gazzar (2005): Abú Bakr al-Gazzar, el poeta de la Aljafería. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias.

- Fernando Andú (2007): El esplendor de la poesía en la taifa de Zaragoza. Zaragoza: Mira.

- José Luis Corral (1998): El salón dorado (novel). Barcelona: Edhasa.

- Arturo Pérez-Reverte (2019): Sidi. Un relato de frontera (novel). Madrid: Alfaguara.

Teaching activities

The top brand

The Taifa kingdoms

What are the Taifa kingdoms? You can find the answer in your history book, on the internet or in one of the publications in the bibliography, if you don’t already know.

In 929, Abderraman III proclaimed himself caliph of Al-Andalus and established his capital in Cordoba, declaring political independence from Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid caliphate.

With the Caliphate of Córdoba, Al-Andalus experienced its period of maximum splendour and stability: there was great economic growth thanks to trade across the Mediterranean and the advance of the Christian kingdoms was halted.

However, the caliph’s authority waned over time and power eventually passed into the hands of Almanzor, a general who imposed a military dictatorship.

After his death, civil war between different Muslim groups (Arabs, Berbers and Slavs) led to the dissolution of the caliphate in 1031 and its division into the so-called Taifa kingdoms. The most important of these were Seville, Toledo, Badajoz, Saragossa, Tortosa, Denia and Granada.

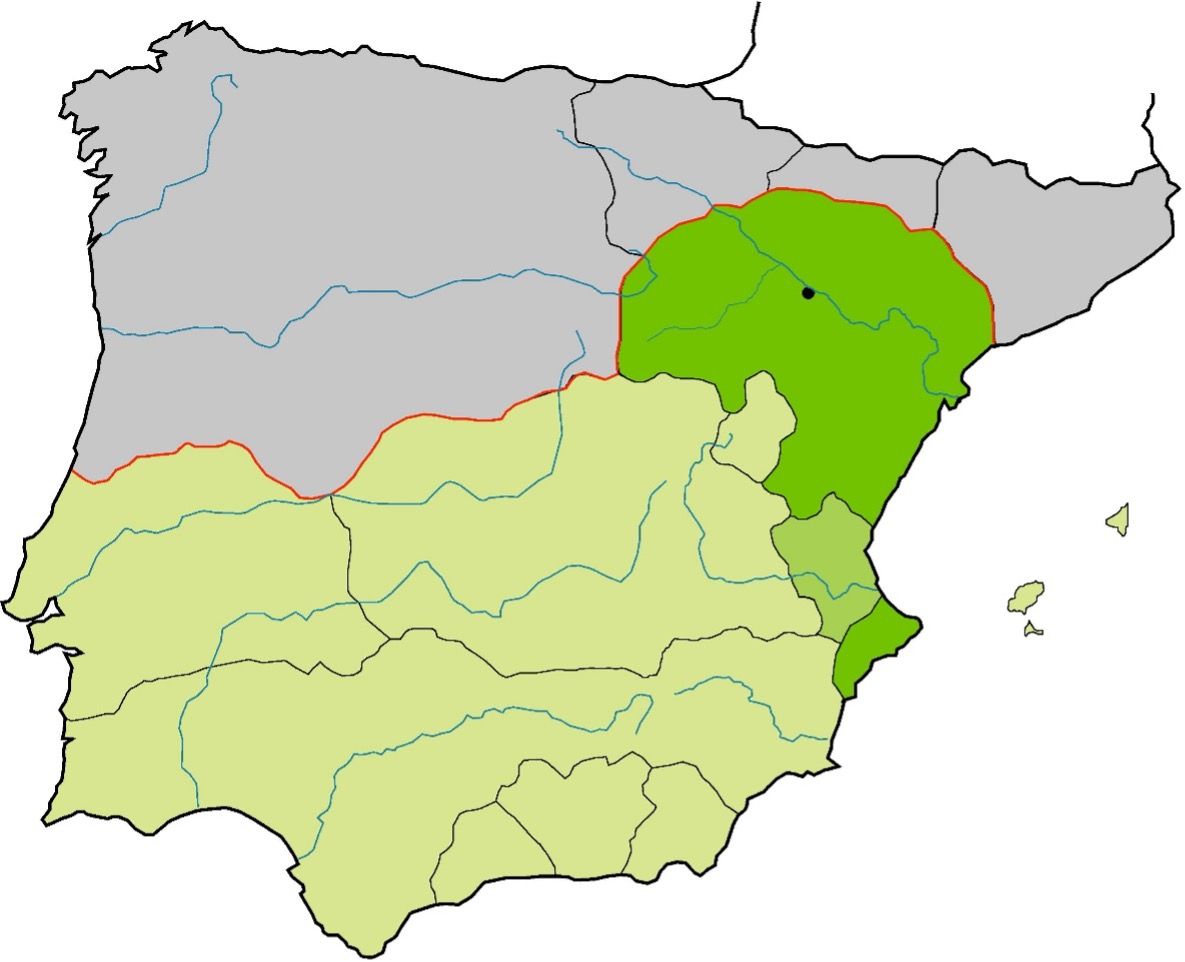

Borders of the Taifa of Saragossa

Look in the text to see which kingdoms the Taifa of Saragossa had borders with during the rule of Al-Muqtádir (1047-1082). Locate them on the map and indicate which were allies and which were enemies.

In the north

- Kingdom of Navarre: Sancho IV, treaty of alliance and payment of parias (taxes).

- Kingdom of Aragon: Ramiro I and Sancho Ramírez, clashes for control of the territories on the northern border.

- County of Barcelona: Counts Ramón Berenguer I and Ramón Berenguer II, clashes over territories in the east.

In the south

- Taifa of Toledo: Al-Mamún and Al-Cádir clashed for control of the Taifa of Valencia.

- Taifa of Albarracín: Abd-al Maliq, between 1045 and 1086 pays “parias” (taxes) to Castile to maintain its autonomy from Saragossa and Toledo.

- Taifa of Denia: Ali Iqbal al-Dawla, conquered in 1076 by Al-Muqtádir.

- Taifa of Valencia: Abu Bakr ben Abd al-Aziz, in 1075 his kingdom becomes a vassal of the Taifa of Saragossa.

To the east

- Taifa of Lerida, Yusuf al-Muzaffar. Long confrontation between brothers over the territory of Lleida, annexed to the Taifa of Saragossa in 1078.

- Taifa of Tortosa: administered by kings of Slavic origin, the last of whom was Nabil Al-Fatá. In 1061 it passed into the hands of Al-Muqtádir.

In the west

- Kingdom of León and Castile: Fernando I, Sancho II and Alfonso VI. The Taifa of Saragossa paid regular tribute so as not to be attacked.

Saragossa and the Aljafería

Saraqusta, the White City. Saragossa in the Hudi period

Town planning

Locate on this map of Saraqusta the main places in the city mentioned in the text. Look for information and explain what they are: medina, new quarters, souks, cemeteries, Jewish quarter, Mozarabic quarter, zuda, main mosque, mosques, churches, gates, medina wall, rammed earth wall

Saraqusta had a white stone wall, made of plaster, from the Roman period. It surrounded the medina and gave it the nickname of Medina Albaida, the White City. Over time, new neighbourhoods were added outside the walled enclosure, which were fortified with a new wall built of rammed earth.

Within the medina was the Aljama mosque, the main mosque, built in the early years of the Islamic occupation and later extended on several occasions as the city’s population grew. In addition to the aljama or main mosque, there were other mosques in the different neighbourhoods.

The Christian population, which was respected, had two temples. In the Mozarabic quarter there was the church of Santa María on the banks of the Ebro and outside the walls the church of Las Santas Masas.

The Jewish population in the Jewish quarter also had its own religious buildings.

The layout of the streets within the medina formed grids, just as the Romans had designed them. However, as the city grew, it adopted a type of urban planning typical of the Muslim world, with narrow, irregular streets.

The Zuda, or governor’s palace, was located at the northwest end of the medina next to the wall, next to the Ebro. On numerous occasions the people from Saragossa rebelled and took the Zuda by force to overthrow a bad governor. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why the Aljafería Palace was built some distance from the city.

The main market or souk was located near the Great Mosque, on the site of the old Roman forum, close to the river from which many goods came from the Mediterranean.

The cemeteries were built next to the city gates, away from the city centre.

Economic activities

Look in the text to see what agricultural products were produced in the market gardens of Saragossa and to find preserved objects made in the city from that period.

Saragossa was one of the richest cities in Al-Andalus. Its location on the banks of the Ebro, a crossroads for numerous trade routes, favoured its industrial and mercantile development.

The proximity of the mouths of the rivers Huerva, Gállego and Jalón, as well as the fertile banks of the Ebro, provided it with a rich and varied market garden. The Muslims knew how to take advantage of and improve the hydraulic infrastructures from Roman times to optimise the production of their market gardens. Several chroniclers from different periods record this:

- Idrisi (12th century) stated that Saragossa was “surrounded by gardens and vegetables”.

- Al Himyari (15th century) commented that Saragossa had “the most fertile territory and the most numerous vegetables” in the whole of Al-Andalus.

- Al-Qalqasardi (15th century) described it in these words: ‘it looks like a white speck in the centre of a great emerald over which the water of four rivers flows, transforming it into a mosaic of precious stones’.

In addition to garden produce, wheat, grapes and olive oil were produced in the area around Saragossa. There are several references to the existence of mills and ovens for the production of bread. The latter were in the hands of the mosques in each neighbourhood and part of the profits obtained were used to help the poorest.

As for the craft industries, the sources are also prolific in their praise of the products that were produced, for example, leather garments, whose industry was located in what is now the district of Las Tenerías; or the workshops producing cotton, hemp, linen and even silk cloth. These fabrics and leather garments, whose embroidery and tailoring were highly appreciated, were known as “zaragozíes”.

Another important local industry was metalworking. Swords and chain mail were made, as well as copper and bronze objects and even silver was worked.

Pottery was undoubtedly another important activity, judging by the remains of kilns, “testares” and pieces found in archaeological excavations carried out in the old quarter of Saragossa.

The necessary raw materials that were not produced in the vicinity of the city arrived via the Ebro, navigable up to its mouth, which connected it with the main ports of the Mediterranean. This also favoured a thriving commercial activity.

During the reign of Al-Muqtadir, in addition to the usual fleece “feluses” (a 50% alloy of silver and copper) and silver dirhams, gold dinars were also minted, reflecting the wealth of his kingdom.

The Aljafería, Al-Muqtádir’s palace

Go and visit the Aljafería. If you don’t have the chance, you can watch the following Youtube video from the Auriga del Arte:

Do you think it bears any resemblance to the buildings of Muslim origin that are preserved in Cordoba or Granada, and what differences do you see with respect to the Christian castles and cathedrals of the period?

The court of Al-Muqtádir

Look up on the internet and in the following text some of the people who formed part of the intellectual circle of the court of al-Muqtádir and write down what they excelled in. For example: the litterateur Ibn Hasday, the mathematicians Abu ‘Abd Allah Assaraqstí and Al-Karmani, and the astronomer Ahmad ben Muhammad Al-Naqqqash.

The Jewish Ibn Hasday, who was the vizier or secretary to three successive kings of the Taifa (al-Muqtádir, al-Mu’tamin and al-Musta’in II), was a prominent figure at his court. He wrote poetry and epistles in Arabic.

Other illustrious Jews lived in the capital of al-Muqtádir, such as the great literary scholar and thinker Ibn Gabirol, who criticised his coreligionists in Saragossa for neglecting Hebrew and using Arabic and Romance instead.

The study of the sciences in the Ebro valley reached a high point. Medicine and pharmacology, astronomy and astrology, mathematics and geometry, and also physics were cultivated. The court of Saragossa excelled in precisely these sciences under the patronage of the Banu Hud, especially al-Muqtádir and his son al-Mu’tamin.

But at the Sarakti court there were also prose writers and poets such as Ibn al-Dabbag, Ibn’Amar, Ibn Ya’far al-Qaysí, al-Husrí, etc. who came to Saragossa from different places, as well as other writers from the Ebro Valley, among whom al-Jazzar, the Butcher, stands out.

The Saragossa of al-Muqtádir in contemporary literature

Read some of the novels mentioned below, which will bring you closer to the period of the Saragossan taifa through fascinating adventures.

José Luis CORRAL, El salón dorado (The Golden Hall)

Juan, a young man sold into slavery in Constantinople, arrives in Saragossa, where he wins his freedom. Converted to Islam, he occupies important positions in the court of al-Muqtádir. He met great figures, travelled to Toledo and Marrakech and, in his old age, experienced the conquest of Saragossa by the Christians. He spent his last years in Fez, in North Africa, where he devoted his time to teaching astronomy.

Arturo PEREZ-REVERTE, Sidi. Un relato de frontera (Sidi. A story of the frontier)

Enjoy the adventures and battles of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the Cid Campeador, first in Castile and then under the orders of the Muslim kings of Saragossa in their struggle to keep their borders safe against their enemies, whether Christian or Muslim.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: