JOHan Ferrández de Heredia

The humanist warrior

Munébrega, circa 1310 – Avignon, 1396

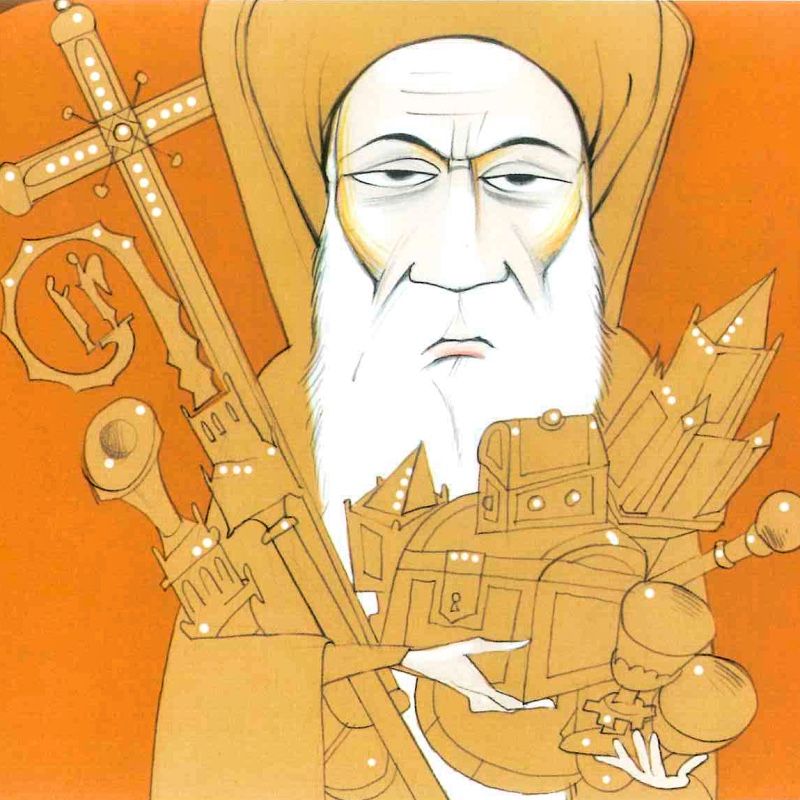

In the Middle Ages, almost more than kings and popes, it was the grand masters of the military orders who wielded the greatest power in Europe. Under their command were concentrated mighty armies of knights dedicated body and soul to battle in the name of Christ and their lord, and in their coffers they accumulated vast sums of money which they lent out as they saw fit. One of the most powerful of these mighty warlords was called Juan Ferrández de Heredia. He was born around 1310 in Munébrega, a small village in the region of Calatayud, and lived a life like a novel.

He came from a family of the lower Aragonese nobility. When she was still very young, she joined the Order of Saint John of the Hospital, known today as the Order of Malta. This had been created in Jerusalem during the first Crusade at the end of the 11th century, like the orders of the Holy Sepulchre and the Temple, and in the 14th century it had its main headquarters on the island of Rhodes, although its possessions stretched from Asia to the Atlantic. Its members were “warrior monks” who had taken a vow of chastity, poverty and obedience. They came to Aragon to confront the Muslims and, thanks to the will of Alfonso I the Battler, they controlled extensive territories.

Johan Ferrández de Heredia rose through the ranks of the order until he occupied the highest position in the kingdom, castellan of Amposta, the title given in Aragon to the Grand Master’s representative. At the same time, he began to work closely with King Peter IV, whom he helped with sword in hand to put down internal rebellions in Aragon and Valencia, to occupy the island of Mallorca and to fight the Castilians.

In 1351, the Aragonese monarch sent him to Avignon, the residence of the popes at the time, to defend his interests. There, he won the confidence of Pope Innocent VI, who commissioned him to mediate, without success, between France and England, embroiled in the Hundred Years’ War, and to direct the defence of his dominions, threatened by mercenary troops. In return for his diplomatic and military services, the pope rewarded him with new posts in the Hospitaller Order in Castile and southern France.

With the accession of a new pope, Gregory XI, to the throne of St. Peter’s, Johan Ferrández de Heredia’s power increased even more. In 1377 he was finally appointed Grand Master of the Order of the Hospital and was entrusted with the task of fighting the Turks. However, on an expedition to Greece he was taken prisoner. After almost two years in prison, he was released in exchange for a large ransom and took refuge in Rhodes.

He was forced to return to Avignon in 1382, for after the death of Gregory XI, four years earlier, the Western Schism had broken out. European Christians had split into two camps supporting two different popes, one based in Avignon and the other in Rome. He remained loyal to the successive popes based in Avignon, especially to his fellow Aragonese, Benedict XIII, the “Moon Pope”, to whom he provided essential financial support during his long mandate.

In the last period of his life, he combined his political work with the promotion of extremely important artistic and literary activities. He sponsored the work of painters from all over Europe, such as Simone Martini, who revolutionised late Gothic painting. Above all, however, he brought together a group of translators to work on texts by ancient Greek and Roman authors. Thanks to his stay in Rhodes and elsewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean, he was able to make contact with local scholars and discover classical works that were kept there. In the scriptorium of Ferrández de Heredia, for example, writings in Greek by Thucydides and Plutarch that were thought to have been lost in Europe were translated for the first time into a Romance language, in this case Aragonese. These versions in Aragonese were subsequently used to translate them into other languages, such as Italian, thus spreading across much of the continent.

Another outstanding facet of the cultural impulse undertaken by Johan Ferrández de Heredia was the production of historical works. He commissioned a Great Chronicle of Spain and also a Chronicle of the Conquerors, in which he reviewed the biographies and deeds of arms of illustrious warlords of the past such as Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus, Tiberius, Attila, Charlemagne, Genghis Khan and James I the Conqueror, among many others. He also recreated the Trojan War and compiled stories of Byzantine emperors and oriental tales, as well as producing an edition of the Book of Marco Polo, which details the travels of this Venetian adventurer.

Johan Ferrández de Heredia died in Avignon in his old age in 1396. His remains were transferred to the San Juanist convent of Caspe and placed in a princely marble tomb, which was destroyed during the Civil War of 1936-39. Despite having taken a vow of poverty and chastity, he accumulated an immense fortune and had at least four children, who gave rise to one of the most prominent lineages in Aragon for centuries.

Most of his magnificent collection of books, among the best in the world at the time, ended up in the hands of Íñigo López de Mendoza, the Marquis of Santillana, while other copies ended up in the library of the aforementioned Benedict XIII.

References

- Juan Manuel Cacho Blecua (1997): El gran maestre Juan Ferrández de Heredia. Zaragoza: CAI.

- Ana Mateo Palacios (1999): Las órdenes militares en Aragón. Zaragoza: CAI 100.

- José Luis Corral (2002): El invierno de la Corona (novela). Barcelona: Edhasa.

- Rafel Vidaller, Mª Ángeles Ciprés (2021): Juan Ferrández de Heredia. Zaragoza: Aladrada.

- A biography: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/9397/juan-fernandez-de-heredia

The University of Saragossa and the Government of Aragon hold a chair dedicated to the promotion of Aragon’s own languages as part of the intangible heritage of our autonomous community, under the name of Johan Ferrández de Heredia. https://catedrajohanferrandezdheredia.lenguasdearagon.org/ferrandez-dheredia/

Teaching activities

Johan Ferrández de Heredia, knight of the Order of the Hospital.

The Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem

Read the following text and make an outline of the administrative organisation of the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Do you know why it was so called? Were there other military orders at the time, which ones, do you know if there were only Spanish or Aragonese military orders, and why they arose?

You can search on the reference website for the positions held by Johan Ferrández de Heredia in the Hospitaller Order and the possessions of that order during his mandate as Grand Master, from 1377 until his death in 1396. You will be able to see the great power he came to wield when he held this post.

Johan Ferrández de Heredia was born into a family of the lower Aragonese nobility. His status as a younger brother did not allow him to inherit any family title, so, in order to ensure his future, he joined a military order, in this case the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, like so many other second-born noblemen. In 1328 he is already mentioned as a knight of the same order.

In the time of Juan Ferrández de Heredia, the Grand Master of this order resided on the Greek island of Rhodes, near Turkey, from where he controlled a complex administrative network. He was in charge of seven great circumscriptions, called “languages”: Provence, Auvergne, France, Italy, England, Germany and Spain [the latter, called “of Aragon” by some authors, was divided in 1462 into the languages of Castile and Aragon, and remained so until the end of the 18th century]. These languages were divided into priories and castellanies. The latter had a more military character and were located in the war zones against the Muslims. The “language” of Spain [or Aragon] was further divided into the priories of Castile-Leon, Portugal, Navarre, Catalonia and the castellania of Amposta. The castellan of Amposta was a vassal of the King of Aragon. The priories and castellanías, for their part, were subdivided into encomiendas under the command of comendadores who acted as lords of the place, governing and collecting a series of taxes destined for the Order’s treasury for the conquest of the Santa.

Johan Ferrández de Heredia, scholar

Read the following texts and try to answer the questions posed.

In the last years of his life Johan Ferrández de Heredia settled in Avignon, where he lived until his death. From Avignon he carried out a great scholarly activity. He formed a scriptorium responsible for copying, translating and writing books on different subjects. Many of the books that came out of it were ornamented with miniature paintings of high artistic quality, in which the master himself was often portrayed; moreover, they were all written in the Aragonese Romance language.

Do you know what a scriptorium is and how it worked? When did they disappear and why? In the film The Name of the Rose you can see how one works.

He had the work Grant Cronica de Espanya written and revised or wrote it himself, which has come down to us quite complete. And also under his tutelage and with his intervention, the Chronicle of the Conquerors, the Book of the Emperors, the Book of the Facts and Conquests of the Principality of Morea, the Flower of the Histories of Orient and the Book of Marco Polo were written.

Select some of the works that Johan Ferrández de Heredia ordered to be written and find out what they contain. Do they all have something in common?

He also saw to the translation into Aragonese of texts by ancient Greek and Roman writers such as Plutarch, Thucydides, the Christian historian Orosius and others.

Do you know any of these authors? Do you know what Plutarch’s Parallel Lives is about? Which war was Thucydides a chronicler of?

He was also concerned with the world of the arts and surrounded himself with prominent artists of the time. His own alabaster tomb, commissioned by him for the San Juan monastery of Caspe, follows models of funerary sculpture of the period. There are similar examples in France, such as the tomb of Philip the Bold of Burgundy, and also in Saragossa, such as the tomb of Don Lope Ferrández de Luna in the cathedral of La Seo.

Look for images and compare the tombs of Lope Ferrández de Luna, buried in 1382; Johan Ferrández de Heredia, who died in 1396; and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, who died in 1404. Highlight the characteristics you think they have in common.

Johan Ferrández de Heredia, European politician

Europe in the 14th century

Throughout his life Johan Ferrández de Heredia travelled around the courts and main kingdoms of his time, either as a representative of the King of Aragon, or as a diplomat in the service of the popes of Avignon, or as a high official of the Order of the Hospital.

At the head of various missions he visited Jerusalem, Rome, Rhodes, Greece, Anatolia and, of course, the courts of Avignon, Paris, Pamplona, Burgos and Saragossa. He was also a prisoner of the powerful Ottoman Turks for two years.

As Grand Master of the Hospitaller Order, he ruled over men, lands and jurisdictions that stretched from Asia to the Atlantic and provided vast resources of all kinds.

Locate and mark on this map the island of Rhodes and the other places mentioned where Johan Ferrández de Heredia was. You can also demonstrate your knowledge of 14th century Europe by clicking on the following link. Can you manage?

Counsellor to the Kings of Aragon and the Popes of Avignon

Johan Ferrández de Heredia was always at the service of the monarchy of Aragon, with Pedro IV for most of his life and in his last years with Juan I. He also assisted different popes at his seat in Avignon.

Look up information on these conflicts of the period and indicate to what extent Juan Ferrández de Heredia participated in them: the War of the Two Peters, the Hundred Years’ War and the Western Schism.

It is striking that such a prominent figure in his time does not have a more recognised role in medieval historiography. Reflect on the causes of this fact.

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA

Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte

Parque Empresarial Dinamiza (Recinto Expo)

Avenida de Ranillas, 5D - 2ª planta

50018 Zaragoza

Tfno: 976 71 54 65

Colabora: